We have decades of data proving design’s business value. So why do we still lose every budget fight?

I’ve watched it happen too many times. You spend weeks researching, prototyping, testing. The users love it. The data backs it. Then someone in the room says “I don’t like blue” or “my wife thinks this is confusing” and suddenly everything’s back on the table. Design decisions get discarded like they’re optional decorations, not strategic choices backed by evidence.

In most companies I’ve worked with, design is an afterthought. Something you add after the important decisions get made. Which means when budget cuts come, when timelines compress, when stakeholders disagree — design goes first. And the worst part? We stand there unable to articulate why that’s a mistake in terms anyone will listen to.

Here’s what makes this infuriating: the evidence that design creates business value is unambiguous. McKinsey studied 300 publicly listed companies over five years and found that top-quartile design performers achieved 32% points higher revenue growth and 56% points higher total returns to shareholders. The Design Management Institute tracked design-led companies for a decade and found they outperformed the S&P 500 by 211%.

Yet design teams get cut disproportionately during layoffs. We lose budget allocation fights. We remain stuck in service organization roles while marketing and product management sit at the strategic table making decisions about what we’ll build.

The problem isn’t that design lacks value. The problem is that we — as a profession — never learned how to prove it in language that organizations understand.

And this isn’t about individual designers being bad at business. This is systemic. This is about how design professionalized, how design education evolved, and how the industry systematically failed to build business articulation capability into our DNA from the start.

John Maeda’s annual Design in Tech reports have tracked design’s rise in Silicon Valley for over a decade, documenting the evolution from “classical design” to “computational design.” His 2024 report carried an urgent warning: “Work Transformation Is Coming FAST” for design careers. Yet even as design’s technical capabilities expanded, its business legitimacy remained precarious.

We inherited a philosophy that actively opposed commercial thinking

The roots go deeper than you’d think. When Walter Gropius established the Bauhaus in 1919, he deliberately positioned design as an artistic and technical pursuit opposed to commercial concerns. The curriculum emphasized “form follows function” and workshop-based learning, but explicitly excluded business, history, and commercial context.

This wasn’t neutral. It established a professional identity centered on craft excellence and creative autonomy — values that positioned designers as separate from commercial enterprise. When László Moholy-Nagy founded the New Bauhaus in Chicago in 1937 and Josef Albers joined Black Mountain College, they carried this DNA into American design education. The pattern replicated through Ulm, RISD, and eventually into the academic design programs that produce most professional designers today.

Mike Monteiro frames this inheritance bluntly in Design Is a Job: designers must understand they’re “running a business, not a hobby.” Yet this framing contradicts the very foundation of modern design education, which positioned commercial concerns as antithetical to craft excellence. While marketing departments in the 1950s-70s were learning to speak the language of ROI and revenue attribution, design schools were teaching students that commercial thinking corrupted creative integrity.

Nigel Cross’s influential 1982 paper “Designerly Ways of Knowing” cemented this separation by establishing design as a “third culture” distinct from both sciences and humanities. While this legitimized design academically, it also reinforced our distance from business disciplines. Cross positioned design cognition as fundamentally different from analytical thinking — valuable insight that inadvertently made cross-functional translation harder.

Compare this to other professions. The Flexner Report of 1910 transformed medical education by standardizing training and establishing clear professional standards. The Carnegie Foundation’s subsequent studies of law, medicine, and engineering identified a pattern: successful professional education combines technical skill with professional identity formation that includes service, responsibility, and yes — business reality.

Design education never underwent equivalent transformation. There was no Flexner Report for design. No moment of standardization that required business competency as part of becoming a professional designer.

So we learned to make beautiful things, thoughtful things, user-centered things. But nobody taught us how to defend them when someone asks “What’s the ROI?”

Design education’s failure to incorporate business competency isn’t new criticism. Don Norman — former Apple VP and author of The Design of Everyday Things — has spent decades advocating for educational reform. In his influential 2010 essay “Why Design Education Must Change,” Norman observed that designers often lack “requisite understanding” of behavioral sciences, technology, and business: “Design schools do not train students about these complex issues, about the interlocking complexities of human and social behavior.” His 2019 Future of Design Education initiative with IBM’s Karel Vredenburg brought together 600+ volunteers to address the gap between design education and professional demands. Yet as Norman noted, “the vast majority of schools [remain] incredibly resistant, unable to change.”

Meanwhile, marketing and product management learned the language of power

Understanding why design gets marginalized requires looking at how other functions earned their strategic seats. The histories of marketing and product management reveal paths we haven’t followed.

Marketing’s strategic ascent took decades. In the 1950s, marketing existed primarily as advertising coordination. By the 1970s, marketers at companies like Procter & Gamble had assumed profit-and-loss responsibility — a critical legitimizing move that forced financial accountability. The CMO title appeared in the 1990s, and by the 2010s, marketing led digital activities in 92% of companies.

The key transition? Marketers learned to speak in revenue attribution, customer acquisition cost, lifetime value — the language finance already understood.

Product management’s rise is even more instructive. The role started with Neil McElroy’s 1931 “Brand Man” memo at Procter & Gamble, defining someone responsible for tracking sales and driving business outcomes. When Bill Hewlett and David Packard adapted this at HP in the 1940s, they created the modern product manager as “voice of the customer internally.”

But the decisive framing came from Ben Horowitz’s 1998 memo “Good Product Manager/Bad Product Manager,” which positioned PMs as “CEO of the product” — explicitly claiming strategic accountability rather than coordination responsibility.

Sociologist Andrew Abbott’s “The System of Professions” (1988) provides the framework for understanding these trajectories. Abbott argues that professions compete over “jurisdictions” — claims of ownership over expert knowledge. A profession gains legitimacy through diagnosis (classifying problems), inference (applying knowledge), and treatment (implementing solutions).

Marketing claimed the customer relationship jurisdiction. Product management claimed product success jurisdiction.

What jurisdiction has design claimed that executives recognize as strategically essential?

Mark Suchman’s legitimacy research (Academy of Management Review, 1995) identifies three forms: pragmatic (“What can you do for me?”), moral (normative approval), and cognitive (taken-for-grantedness). Cognitive legitimacy is most powerful but rarest.

Marketing and product management have achieved cognitive legitimacy in most organizations — their presence at strategic discussions is assumed. Design remains trapped at pragmatic level, constantly having to prove immediate utility.

The metrics we use don’t connect to decisions executives make

Here’s where the disconnect gets concrete. Designers measure experience quality: task completion rates, System Usability Scale scores, Net Promoter Score, user satisfaction surveys.

These metrics measure something real. But as Jared Spool observed: “The metrics out of the box didn’t help us one little bit. They just created confusion.”

The problem isn’t that NPS or SUS are invalid. It’s that they exist in a different causal chain than executive decision-making. Look at the structure:

Marketing: Revenue attribution → Direct (clicks → purchases)

Engineering: Delivery metrics → Direct (code → features)

Design: Experience quality → Indirect (experience → satisfaction → loyalty → maybe revenue)

Marketing demonstrates that campaign X generated Y dollars through clear attribution. Engineering demonstrates that sprint Z delivered features A, B, C. Design demonstrates that usability improved by some percentage — and then hopes executives connect this to business outcomes.

Design leader Peter Merholz captured this fundamental tension in his Design Leadership Truisms: “YOU CANNOT CALCULATE AN ROI FOR DESIGN.” This isn’t defeatism — it’s acknowledgment that design’s impact is diffuse, systemic, and resistant to the neat attribution models that executives expect.

Research from behavioral economics explains why this indirection kills influence. Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory established that people weigh losses approximately twice as heavily as equivalent gains. Thaler’s mental accounting research showed that people categorize money into different mental buckets with different decision rules.

The implication: design investments positioned as abstract improvements compete poorly against investments positioned as loss prevention or direct revenue generation.

The McKinsey Design Index study quantified this disconnect: over 40% of surveyed companies don’t talk to end users during development, and less than 5% reported that their leaders could make objective design decisions. Design isn’t measured with the same rigor as time and costs — and designers “have not always embraced design metrics or actively shown management how their designs tie to meeting business goals.”

Even NPS itself is crumbling. According to CMSWire’s 2025 analysis, NPS fell from second-most popular CX metric in 2023 to eighth place in 2024. Only 23% of U.S. enterprise CX leaders now use it. The metric’s critics note weak correlation to actual behavior, lack of diagnostic capability, and score volatility — problems that make it unreliable for executive decisions even when designers treat it as gospel.

We’re speaking a language executives don’t use to make decisions. And then we’re surprised when our arguments don’t land.

Real layoffs reveal the cost of not knowing how to defend our worth

The consequences manifest most visibly during organizational stress. Lawton Pybus’s analysis of 2022–2024 tech layoffs, tracking 5,521 laid-off employees across 12 companies, found that while engineers made up the largest share of layoffs in absolute numbers, when adjusted for team size, designers were cut at 1.7 times the expected rate, and researchers at three times the expected rate. In other words: design and research teams were disproportionately targeted.

The UX Collective’s 2024 State of UX report, authored by Fabricio Teixeira and Caio Braga, identified what they call “late-stage UX” — comparing the current industry state to late-stage capitalism. Their analysis of over 1,000 articles from 2023 found design characterized by “market saturation, heavy focus on financial growth, commoditization, automation, and increased financialization.” Designers can now only push so far when advocating for user needs against corporate influence. Matej Latin’s 2023 survey of 293 designers found that 14.3% were laid off — a staggering increase from 2022, when layoffs weren’t significant enough to track.

Indeed’s job posting data showed UX Research positions decreased 89% from their 2022 peak to January 2024.

Jared Spool, in his January 2024 analysis “Why is the UX job market such a mess right now?”, pushed back on the myth that UX was disproportionately targeted: “There’s no evidence to support this. When Meta laid off 21,000 people in 2022 and 2023, a few hundred were UX people… UX people were never more than a small proportion of the total people let go.” Yet this statistical nuance provides cold comfort — whether designers were targeted specifically or caught in broader cuts, the result remains: design teams shrinking, roles disappearing, and a profession unable to articulate why this is strategically catastrophic.

Google Cloud’s October 2025 layoffs cut 100+ design-related positions, with some design teams reduced by half. The pattern repeats: when cost-cutting pressures intensify, design becomes expendable because its contribution remains unquantified.

I’ve seen this up close. Talented designers with years of institutional knowledge, cut because nobody could articulate their business value in the thirty seconds it took finance to scan the headcount spreadsheet.

Intuit’s 2007 Design for Delight launch illustrates how articulation failures play out even with executive support. Founder Scott Cook invited Intuit’s top 300 managers to an off-site to introduce design thinking. He delivered a five-hour PowerPoint presentation. The result: “Polite, yet unengaged response.”

Then Stanford’s Alex Kazaks presented for one hour using hands-on exercises. Two-thirds of participants said most of what they learned occurred in Kazaks’ session.

The lesson: even well-intentioned design advocacy fails when it relies on abstract arguments rather than experiential demonstration and financial connection.

PepsiCo’s Chief Design Officer Mauro Porcini (2012–2025) identified three phases design leaders face:

Denial (“The company doesn’t understand that they need you”),

Hidden Rejection (“Everybody’s nice in meetings, then as soon as you’re out, they’re like, ‘Okay, let’s go back to real life’”),

and Occasional Leap of Faith (“You find some people, the co-conspirators, that decide to bet on you”).

Porcini built a 400-designer team and won 1,800+ design awards — but only after finding executive “co-conspirators” willing to champion design’s strategic role.

This pattern of organizational resistance isn’t unique to PepsiCo. Peter Merholz, in his “Finding Our Way” podcast interviewing senior design executives, identified a consistent theme: “Design leadership is change management.” As Katrina Alcorn, GM of Design for IBM, told him: “We’re change agents because all of us doing this are still part of a movement to change how businesses work, how they run.”

Apple’s post-Ive trajectory reveals what happens when design loses its executive champion. After Jony Ive’s 2019 departure, nearly his entire 24-person design team left — Evans Hankey, Tang Tan, Duncan Kerr, Jody Akana, and more than a dozen others. Design’s strategic position at Apple depended on Jobs’s protection and Ive’s access; remove those, and organizational gravity pulled design back toward service function.

We’re speaking different languages and don’t even realize it

The communication divide operates at multiple levels. Carlile’s 2002 research on knowledge boundaries identifies “syntactic boundaries” from differences in vocabulary and protocols between professional groups. When designers say “user pain points” and executives hear vague qualitative concerns rather than quantifiable friction costs, both sides are speaking accurately from their own frameworks — and neither is communicating.

Recent data quantifies the scope: 78% of organizations report significant barriers between technical departments, 65% of project failures stem from poor communication between teams, and 82% of companies lack unified success metrics across departments.

Design’s articulation problem exists within this broader organizational communication failure — but we’re uniquely disadvantaged because our native vocabulary diverges most sharply from financial language.

Kim Goodwin, who spent decades teaching designers stakeholder communication at Cooper, observed the deeper problem: “It’s not about just doing great design; that’s maybe half the problem. I think that’s actually less than half the problem.” The other half? Understanding how decisions actually get made in organizations — and speaking that language fluently.

Research on boundary spanners defines effective cross-functional communicators as those “familiar with the various professional vernacular and routines of different organizations.” This capability is learnable. But design education doesn’t teach it.

Framing research from behavioral economics explains why the direction of translation matters. Tversky and Kahneman’s work shows that identical information presented differently leads to different decisions. Loss framing proves more persuasive for action than gain framing.

The implication: “We improved usability by 15%” loses to “We’re losing $500K annually to poor checkout UX” — same reality, radically different executive response.

I learned this the hard way. Early in my career, I’d walk into stakeholder meetings armed with beautiful research findings, usability scores, user quotes. I thought the quality of the work would speak for itself.

It didn’t. What worked was translating those findings into their terms: “This redesign will reduce support tickets by 40%, saving approximately $200K annually in customer service costs.” Suddenly, people listened.

The work didn’t change. The language did.

Where design actually wins shows us what’s missing everywhere else

The counterexamples prove instructive. IBM’s design thinking transformation (2012–2020) under Phil Gilbert demonstrates what systematic change requires: $100+ million investment, growth from ~100 to 3,000 designers, 100,000 employees certified in design thinking, and product time-to-market reduction of 50%.

But Gilbert’s insight was strategic positioning, not just capability building. He created internal “brand” by avoiding preconceived terms: “I could either change 400,000 minds, or create a concept that meant nothing at IBM and define it ourselves.”

He made design services something teams paid for, creating demand rather than mandating adoption. He secured CEO sponsorship (Ginni Rometty). He created measurement frameworks connecting to business outcomes (Forrester documented 300% ROI). He built organizational structures that institutionalized design influence.

Airbnb’s design influence stems from structural advantage: cofounders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia are RISD-trained designers. Design DNA existed from inception. But even Chesky admitted at Config 2023: “Getting design in the boardroom wasn’t easy… For 10 years, I was apologizing about how I wanted to run the company because how I really wanted to run the company was as a designer, but I didn’t have the nerve.”

Capital One’s 2014 acquisition of Adaptive Path represented a different approach: acquiring external legitimacy rather than building it internally. The combination enabled systematic design integration producing measurable outcomes — including eliminating overdraft fees after user research revealed customer frustration patterns.

Industries where design holds obvious strategic position share characteristics: consumer electronics (where experience IS the product), automotive (where design commands premium pricing), luxury goods (where aesthetic value is explicitly monetized), and digital products with network effects (where engagement drives the business model).

In these contexts, design’s contribution requires no translation because the causal chain is self-evident.

For the rest of us? We need frameworks.

The frameworks that actually work

Several approaches have emerged to bridge design’s measurement gap, each with documented effectiveness.

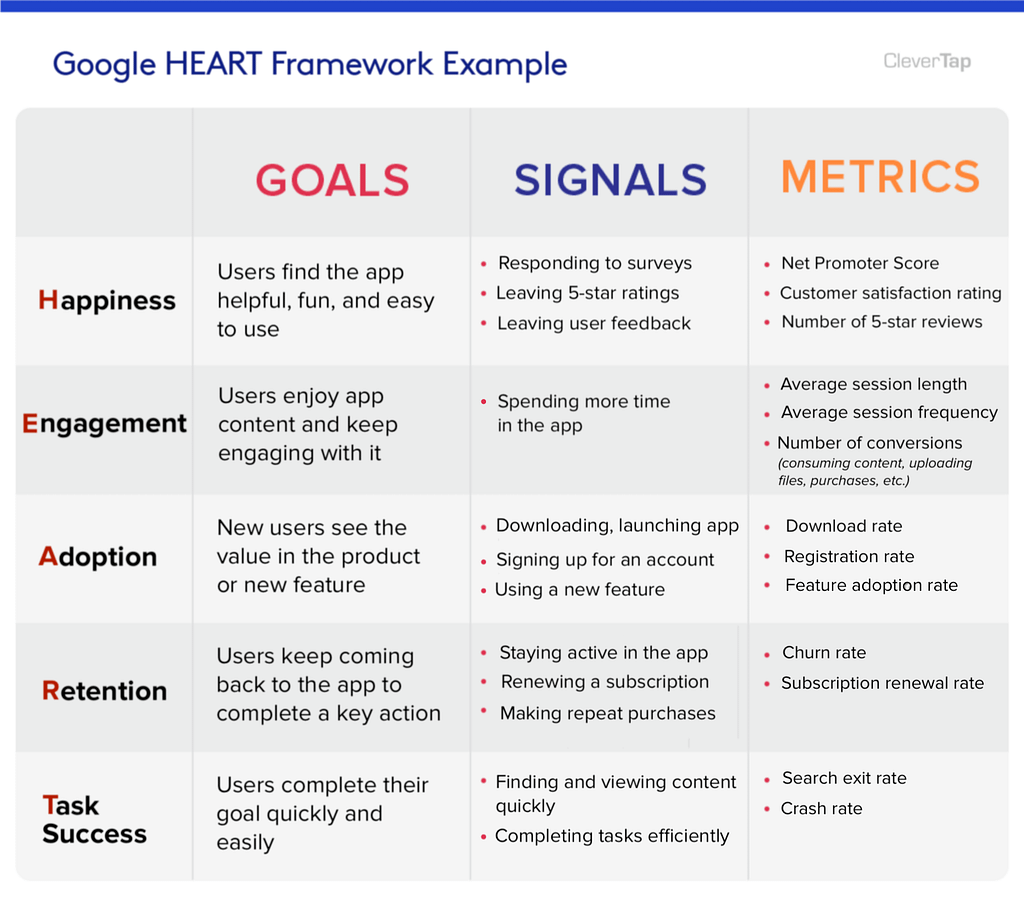

Google’s HEART framework structures UX measurement around Happiness, Engagement, Adoption, Retention, and Task Success — combined with Goals-Signals-Metrics process to connect product goals to measurable outcomes. Kerry Rodden, Hilary Hutchinson, and Xin Fu developed HEART in their 2010 CHI conference paper “Measuring the User Experience on a Large Scale: User-Centered Metrics for Web Applications,” specifically to fill the gap between small-scale qualitative observations and large-scale automated measurement.

Google uses it internally across products. The Gmail “undo send” feature emerged from happiness metrics tracking.

Jared Spool’s outcome-driven metrics, detailed in his famous “$300 Million Button” case study, focus on “problem-value metrics” — quantifying UX obstacles in dollar terms. An e-commerce company identified checkout failures through usability testing, created a custom metric (“unrealized shopping cart value from password issues”), implemented guest checkout, and recovered $300 million annually.

The metric framing transformed “registration causes friction” into financial language executives understood. Spool’s principle: “Surface the cost of not removing obstacles — this gives executives a perspective about UX they’ve never had before.”

Nielsen Norman Group’s ROI framework attempts direct financial calculation, though they appropriately note that “ROI calculations are strategic exercises to help you conceptualize the relative value of design projects. They are not financial projections.”

The methodology: identify specific business metrics affected (revenue, cost savings, productivity), establish baseline and target values, calculate investment cost, project time to achieve targets, and compute ROI.

Les Binet and Peter Field’s advertising effectiveness research offers lessons from a discipline that solved its measurement problem. Analyzing nearly 1,000 advertising case studies spanning 30+ years, they established frameworks that created evidential infrastructure design currently lacks.

Advertising’s effectiveness awards, shared databanks for meta-analysis, and common measurement frameworks built the credibility that design needs.

What needs to change (and who needs to change it)

The research points toward structural interventions, not individual heroism. This problem is systemic. Solutions must be too.

Design education must incorporate business competency as core requirement. The Johns Hopkins/MICA Design Leadership MA/MBA and IIT Institute of Design MDes/MBA programs exist because the market recognizes this gap. But such programs remain exceptions.

Mainstreaming business literacy into undergraduate and bootcamp design education would address the problem at source.

Professional organizations must build measurement infrastructure. Shared databases of design effectiveness case studies, common metrics frameworks, longitudinal research programs would provide the evidential base we currently lack. The McKinsey Design Index and DMI Design Value Index demonstrate the concept’s power.

Designers must learn to speak both languages without abandoning native expertise. This isn’t about becoming business people who do some design. It’s about developing boundary-spanning capability that research identifies as critical for cross-functional influence.

Organizations investing in design must create structural legitimacy. IBM’s transformation worked because Gilbert built organizational infrastructure — not just because IBM hired designers. Design Program Offices, certification programs, embedded teams, executive sponsorship.

And for those of us in the trenches right now?

Start translating. Every design recommendation you make, every research finding you present — ask yourself: “How would I frame this in terms of revenue, cost reduction, or risk mitigation?”

It feels reductive at first. It feels like we’re reducing craft to spreadsheets.

But here’s the thing: the alternative is watching your best work get discarded because someone in the room didn’t like the color blue.

The paradox we need to resolve

Jodi Rae, when creating the Design Value Index, captured design’s fundamental challenge: “People who are convinced of the value of design are not interested in quantifying it. The CEOs in all of the DVI companies already understand the power of design… Those most interested in quantifying the value of design are the financial people, which shows they don’t really understand the power of design.”

This paradox isn’t inevitable. It’s the predictable outcome of a profession that built exceptional craft capability while neglecting business articulation capability.

The good news? This problem is structural, not inherent.

Marketing learned to prove ROI. Product management learned to claim strategic accountability. HR learned to speak in financial terms. Data science learned to demonstrate decision impact.

Each discipline underwent professionalization transitions that design has yet to complete.

The research suggests this transition is achievable — but requires coordinated action: education reform, professional infrastructure, organizational change, individual development.

We’re not the cause of this problem. But we’re positioned to catalyze its solution.

Design’s business value is empirically demonstrated. The task now is building the professional infrastructure to articulate it — to translate craft excellence into language that organizational decision-making recognizes and rewards.

Because the alternative is watching another generation of talented designers get laid off while someone in finance looks at a spreadsheet and decides design is optional.

It’s not. And it’s time we learned how to prove it.

When your best work gets tossed was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.