How the tech industry ended postmodernism and increased individualism

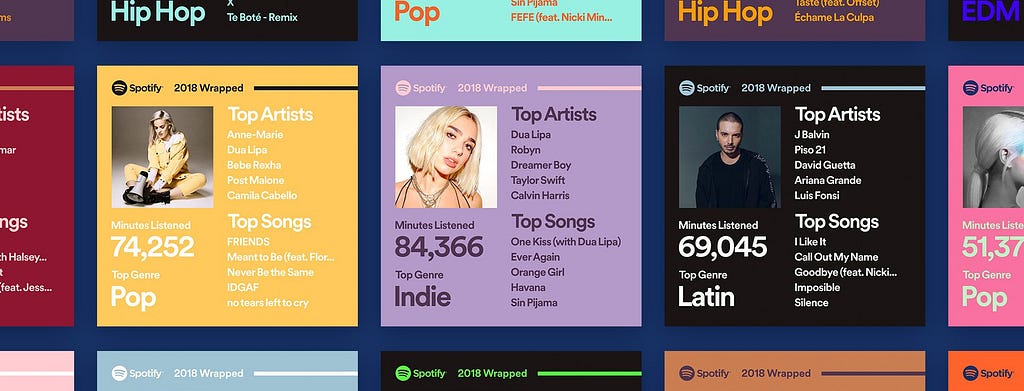

Wham!, Coca-Cola commercials, and obligatory family dinners; Western Christmas weeks are very predictable. We even have a new December tradition: the annual Spotify Wrapped.

At first glance, the concept seems like a brilliant marketing strategy, but there’s a deeper meaning behind it. Why do these recaps go viral? Why do people want to share the music they listened to?

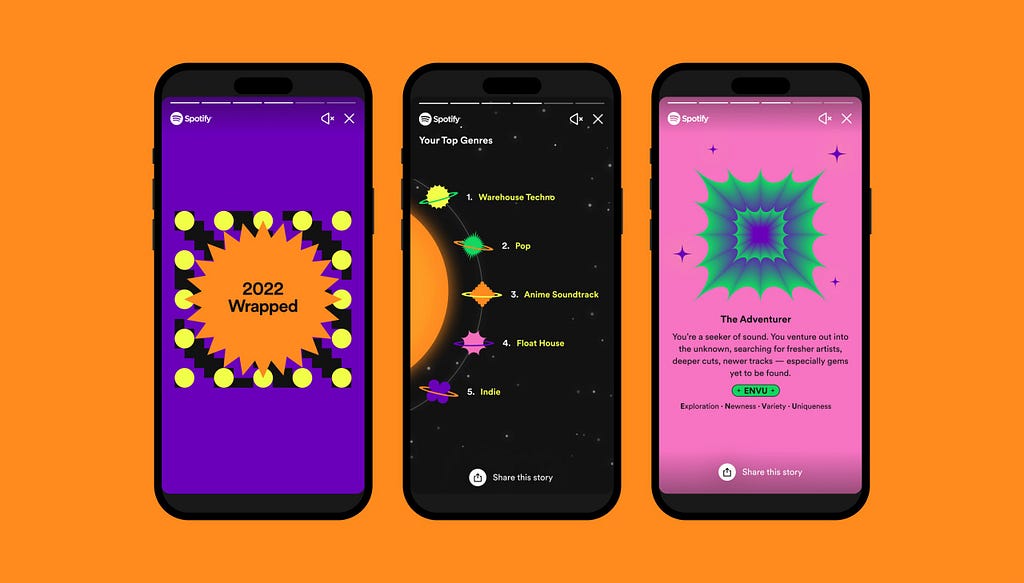

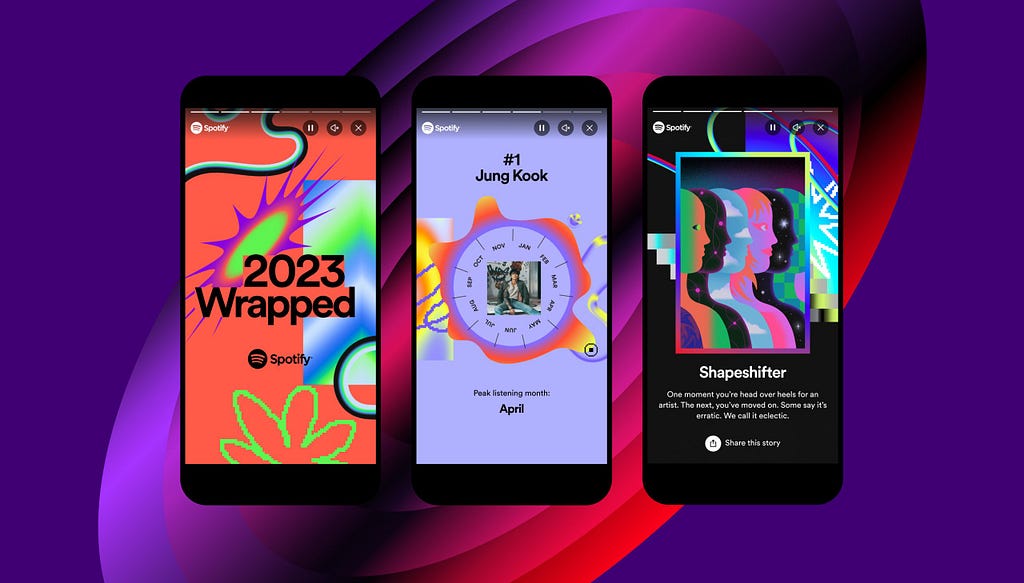

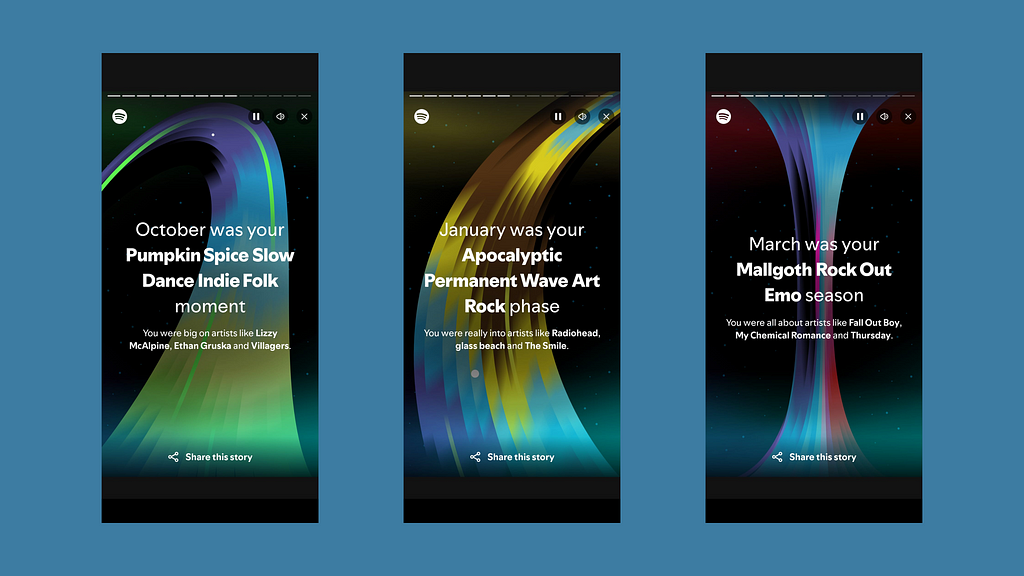

Spotify tells me, “In 2024, you went through your Apocalyptic Permanent Wave Art Rock phase.” What on earth? What does this even mean? Is this really worth sharing?

If Spotify Wrapped had existed in the early 1900s, most lists would have looked the same: “Your favourite artists were Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, and Frank Sinatra.”

Society had changed during the latter half of the 1900s. Wrapped would have been subculture-based. “You are a Grunge rocker, your favourite artists are Alice in Chains, Soundgarden, and Nirvana.” Or, “Hey, Hip-hopper, you mostly listened to 2Pac, Biggie, and Wu-Tang Clan.” These subcultures are largely gone in today’s age.

People currently have highly individual listening patterns. Spotify caters to this with its Spotify Wrapped but also with AI-generated personal playlists and song recommendations.

In this article, I will examine personalisation in Spotify and apps from other industries. I will investigate how music consumption has changed over time and how personalisation has contributed to Spotify Wrapped’s cultural importance.

How people became “different”

We must distinguish three distinct periods: modernity, post-modernity, and cyber-modernity.

During the age of modernity, between the Enlightenment and the 1960s, individuals didn’t have much consumer choice. The creative world was mainly accessible to the elites only, products were mostly locally produced, and the daily lives of the working class were primarily dedicated to work and family.

This isolated life resulted in somewhat monolithic cultures. The average person had only access to regional radio stations, they would buy trousers and skirts in the clothing store downtown, and their opinions were shaped in the local pub/tavern/ale house. Most people, therefore, looked nearly identical and listened to similar music. The market decided for the people. People simply adapted to the products they were offered.

In the 1800s, the upper and middle class would specifically go to the theatre to enjoy a symphony or opera. They would buy a ticket and commit their full attention to consuming the music.

With the invention of the radio and the record player, it became possible to bring music to the living room. Families would gather around the speakers and listen to the news, stories, or music.

In the 1940s, car radios became widespread, so individuals began listening to music while on the move. The number of artists was still minimal, so individuals in the late modern times mostly listened to Duke Ellington’s, Benny Goodman’s, and Glenn Miller’s Big bands. The grand narrative of music moved from classical music in the 1800s to jazz in the early 1900s.

Life drastically changed during the postmodern era, which started in the ‘60s. The post-war industry brought a ton of new possibilities. New communication techniques and cheaper transportation methods led to a global economy.

Consumers started to have vastly more choices and spare time. Thus, they could dedicate more energy to their identity, fashion, and hobbies. Subcultures emerged. Kids started rock and roll bands, and acted in conformity with whatever was required by their subculture’s ways.

Musical instruments were now widely available, and the middle class embraced their musicianship; the number of bands grew dramatically. Philips invented the cassette tape in 1963. Subsequently, recording demos for bands was made possible, and making mixtapes for someone’s teenage crush became a way to show affection.

The first personalised playlists were born. When Sony introduced the Walkman in 1979, people could even listen to these playlists during their public transport commute. People had less mental capacity to fully consume the subtleties and tensions in music, so music needed to become simpler. However, music also transitioned into less complicated compositions because non-conservatory musicians wrote songs.

Music became increasingly background entertainment rather than a primary activity. It also became siloed. The grand narratives of classical music and jazz were left behind, and subcultures emerged.

Subcultures partially arose because electronic instruments allowed for a variety of choices. Electric guitars paved the way for a great assortment of rock music, while synthesisers and beatboxes were foundational for rap, dance, and pop music.

The different genres adopted unique fashion trends and became associated with social and political movements. Rebels preferred punk music and skateboard aesthetics, romantic teenage girls adored boy bands and magazines, and football hooligans embraced underground dance music and sportswear.

Companies likewise jumped on this trend and created brands that would facilitate the desire of certain people (MTV, magazines, and fashion brands).

In the late ’90s, internet access turned mainstream, and kids could now consume an even more multicultural and varied culture/pop diet.

Internet forums and social media arose so people from all around the globe could connect. The possibility of finding cultural peers beyond someone’s subculture evolved. Tech companies and their products became more sophisticated so they could use their smart systems to satisfy users on the level of individual needs instead of on the level of group desires.

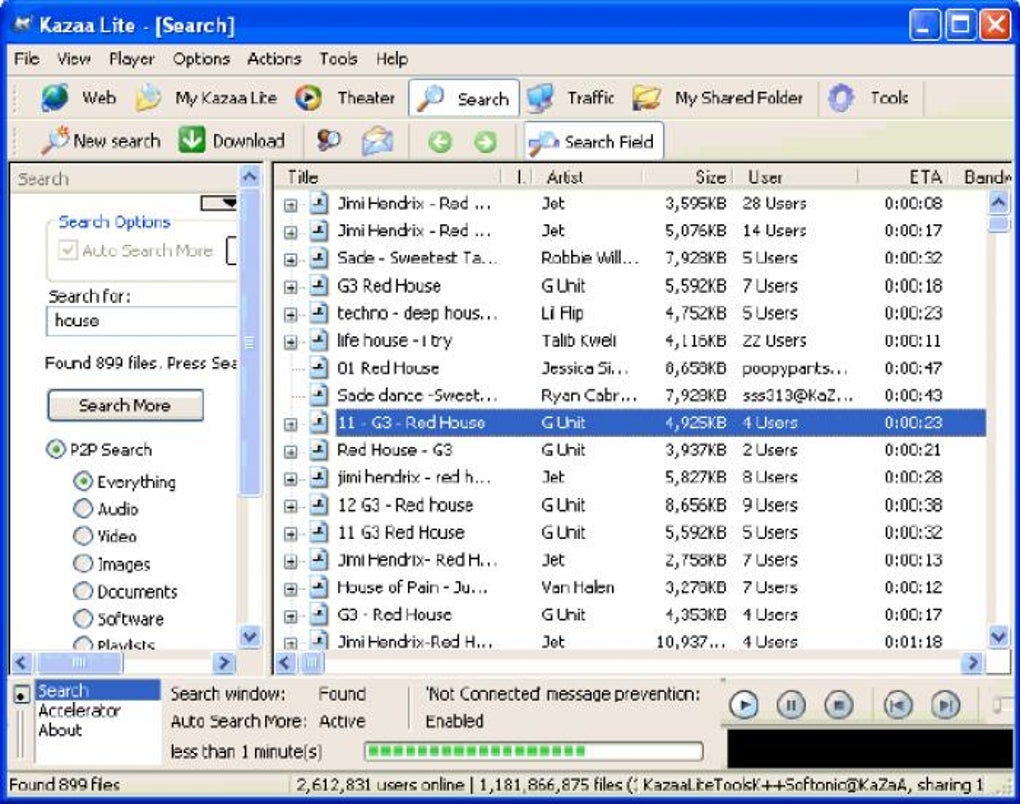

Music consumption has drastically changed this century. Internet downloads through Napster and Kazaa and music players like Winamp have made consumers increasingly focus on individual tracks rather than complete albums.

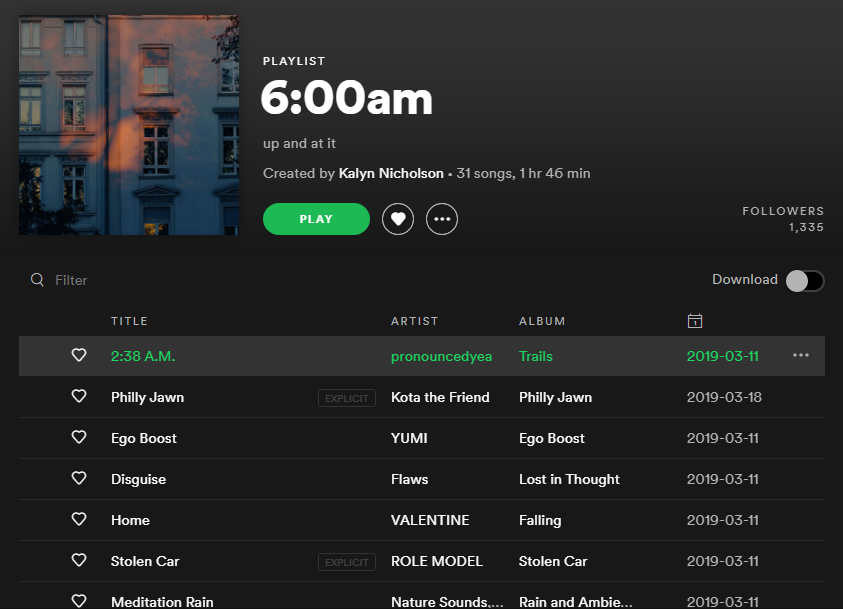

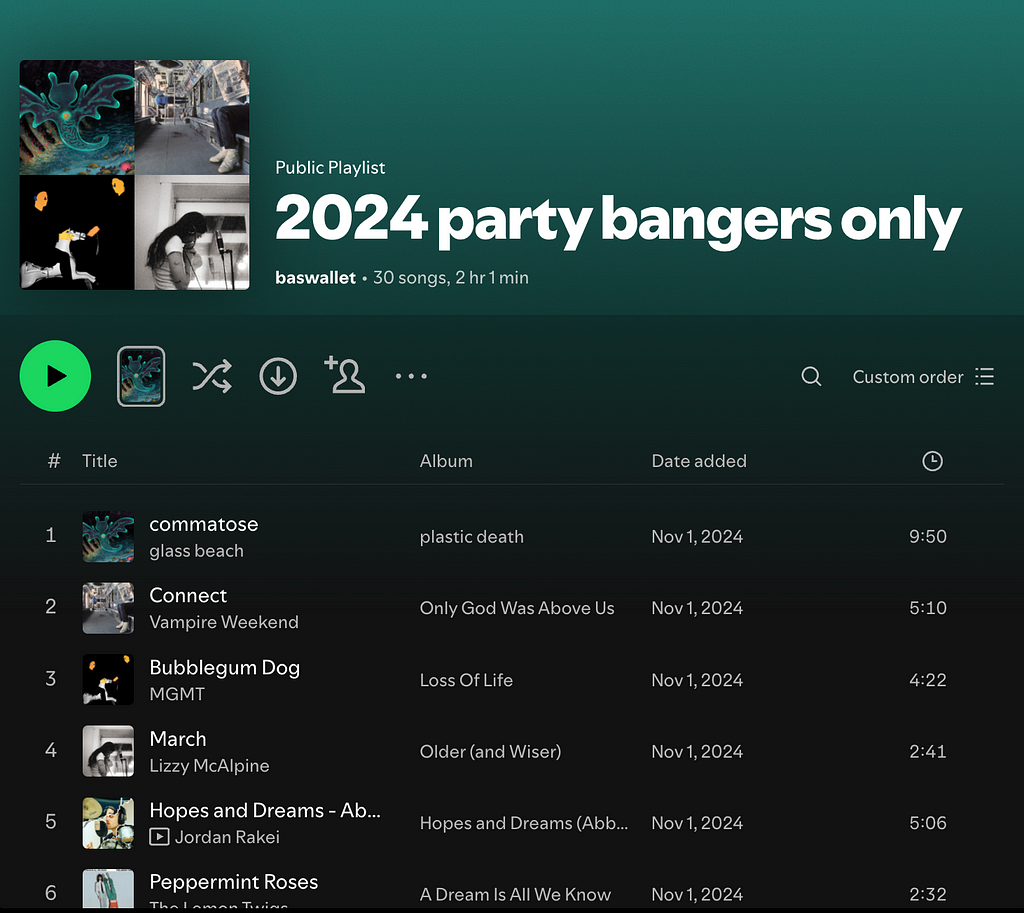

This was further developed with the birth of streaming services like Spotify. All-you-can-listen services enabled music lovers to create their own unique and personal playlists, triggering the further destruction of the grand narratives.

Society went from radio host-driven music experiences, via vinyl and CD record purchasing, guided by genre sections in the record store, to Spotify giving users complete control over their playlists.

This last era, the one of this century that succeeds postmodernism, is labelled in a variety of ways; performatism (Eshelman), hypermodernism (Lipovetsky), altermodernism (Bourriaud), and metamodernism (Vermeulen & Van den Akker).

I believe the online component has the most significant impact and would therefore consider digimodernism the most adequate label, a term coined by Alan Kirby in his 2009 book Digimodernism: How New Technologies Dismantle the Postmodern and Reconfigure Our Culture.

I would personally propose cybermodernism, or even cyberism (so that modernism can be left entirely behind). But we are already swimming in terms, so forget about my proposal.

If you want to read more about the distinction between modernism and postmodernism, you can read: How technology and the Beatles changed art, sex, work, and truth

The impact on music

In the early 1900s, theatre visitors had the stamina to sit through a complete Mahler or Shostakovich symphony. In postmodern times, Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of The Moon, Depeche Mode’s Violator, and Radiohead’s Kid A were considered holistic music productions that ought to be listened to as entire records. Yet, in the digimodern era, users began to cherry-pick songs.

Spotify recently changed its interface so the unique artists of each track became more visible, indicating that listeners have moved increasingly from having playlists of a single artist to collections of various artists.

Smart algorithms likewise allow for continuous playing, similar to infinite scrolling designs on social media or dating apps. This results in a user experience where content never ends. Consumers can always skip a track/video/date because the next track/video/girlfriend will be available anyway. This leads to a microwave mentality. People want instant change and satisfaction.

Artists don’t have a choice but to write their songs to grab the listener’s attention directly; the ‘skip’ button is quickly used. Therefore, the time it takes for a song to hit the ‘hook’ has drastically decreased. Led Zeppelin could easily get away with a 4-minute guitar intro, but contemporary pop artists must rush to their chorus to avoid losing the listener’s attention.

Music likewise moved from being the primary entertainment source (theatre) to a background activity. The mechanics of music theory go beyond the scope of this text, but popular music, especially its chords and progressions, did become significantly simpler.

Despite this simplification, music needs tension to be enjoyable. All forms of art rely on a form of tension and release. Without tension, the satisfaction of the resolution doesn’t occur.

Throughout the last 100 years, we’ve seen a shift from creating tension through dissonant notes to using modern production techniques to add tension. Today’s music relies greatly on interesting beats or sound layers and textures—something postmodern bands couldn’t use.

Listeners also have access to sound gear with a much more expansive sound frequency range, allowing producers to add more subtleties to the music’s low end (low notes).

In modern times, tension was created through clever compositions. The piano would play ‘weird’ notes, and the violins would add contradicting parts. In postmodern times, distorted guitars, shouting vocals, and stadium rock drum kits created discomfort. In digimodern times, engaging beats and soundscapes drive listener engagement.

Lyrics likewise become considerably more emotional and personal. David Bowie, Bob Dylan, and the Beatles repeatedly used fictive personages to tell a story. Kurt Cobain, Eddie Vedder, and Jeff Buckley conveyed their emotions vastly more from the heart. This trend continued with the emo-movement in the early 2000s.

Today, most pop music is deeply personal, thus adding a different type of tension together with the compositional tension. Spotify offers a feature that allows listeners to view the lyrics alongside the music.

Spotify’s commercial motives

Spotify uses a standard freemium model, offering a free tier with ads and a premium tier with subscription fees. For companies like Spotify, user growth is essential. The more users they have, the more behavioural data they collect. This allows them to improve their product, engage (or addict) users further through personalisation, and cater for their business partners (investors, venture capitalists, advertisers, and record labels).

User churn rate is one of the most substantial performance metrics. This metric tracks how quickly and with what magnitude users unsubscribe. Spotify, like most Silicon Valley-type companies, has a growth team that uses data analytics, user interviews, and market trends to identify strategies for locking in users.

Spotify Wrapped plays a vital role in keeping these users. The mechanism is part of a social ritual many people don’t want to miss out on. Unsubscribing from Spotify means someone would lose their December habits, potentially at the detriment of social status.

The more Spotify knows about a user, the more personalised their annual Wrapped is, and the better Spotify can create a UX that adapts to the user’s habits and desires. Personal playlists and recommendations are valuable tools, but it’s not hard to imagine a future where AI will be used to generate even more personal experiences. Music and lyrics can be adapted based on personal data. Sooner or later, you might have your personal “musician”.

Spotify has another financial incentive to use AI to generate music. AI music would give them the royalties of this music, pushing out the original creators and further expanding their market dominance. Spotify already has this concept rolled out in background music playlists for concentration (chill jazz café or concentration minimal electronic). AI artists are now also being pushed.

Other domains of personalisation

Spotify is not unique in applying personalisation but is part of a global trend. Other industries must be examined to understand how personalised playlists impact individual lives.

The film industry went through a similar transition as the music industry. It moved from modern-time film fanatics going to the theatre, via postmodernists picking a film based on an array of TV channels or borrowing a VHS tape, to digimodernists having a streaming service with infinite choices that will recommend a handful of films.

Modernist shoppers would go to the local fashion store to buy the only jeans available, whilst in postmodern global times, with reduced transportation and production costs, mail-order catalogues and shopping malls offered much more choice. Digimodern online stores like Amazon or Zalando give shoppers unlimited choice whilst recommending a specific personalised selection of items.

In the early 1900s, families ate their domestic food specialities, but with immigration came a variety of food choices. Indian, Indonesian, and Italian food options became obtainable. The digimodern food delivery apps now provide numerous food options and recommendations.

Online dating

Perhaps the best example of the trend that takes society from a modern monocultural society to fragmented identities is the world of dating and sexuality.

The modern man would find his girl-next-door in the church or a village sports club. The modern man was straight, and so was the modern woman. The sexual revolution of the 1960s brought change. Women started to be increasingly empowered, and homosexuality slowly became accepted.

Postmodern dating life moved from the church to the nightlife scene, and partygoers could find like-minded individuals compatible with their subculture. Homosexual people could find peers in gay bars.

The digimodern search for dates has largely moved online. This means that it would be much easier to find people with the exact characteristics someone would desire.

The sexual silos of being straight or gay could therefore be dismantled. Digimodern sexual identities are entirely fragmented. Dating apps give users an abundance of personal filters and sexual preferences, from pan, bi, or queer to gyno, objetum, or skoliosexual.

The impact on people

This article outlines how the world has moved from a single-choice modern time, via pluri-choice postmodern decades, to unlimited-choice digimodernism. The importance and role of our identities align with these trends.

Music listeners moved from fitting into the modernist social convention, via being a member of a subculture, to being entirely unique.

Spotify facilitates this transition by offering its Discover Weekly and Daily Mixes playlists. Together with these personalised playlists, Spotify also offers a continuous play function. The software analyses the content of a user’s playlist and will continue playing songs that match the specific songs in this playlist.

Nowadays, users’ listening patterns are so unique that this can push them into an existential crisis. What is their musical identity? Is their listening behaviour consistent with their personality? How do they convey who they are to their social environment?

The sheer importance of Spotify Wrapped is now visible. The mechanism allows users to share who they truly are with everyone who wants to see it — or so users believe.

In modern times, individuals adapted their behaviour to the few products available. Digimodern products adapt to their users. Adaptive design is a term frequently used in the UX world. What does that tell about people and products?

Is society going through a Copernican revolution in the product industry? This transition came in the 1990s when Don Norman introduced our craft, User Experience Design. He radicalised the design industry and placed the user, not the company or technology, at the centre of design.

Is the individual now at the centre of the universe? Does that make society literally ego-centric? The world has undoubtedly turned into a hyper-personal society. However, this phenomenon is still culturally dependent.

The US is uniquely individualistic and can’t be compared with Europe, where individualism is important but integrated into social trends. Many Asian and African countries have more collective than individualistic characteristics. Individuals in Asia are more a representation of someone’s family or tribe than a product of their individual choices.

Who are we?

If we philosophise about individual identity, the French existentialists are logical to name first. Jean-Paul Sartre makes the case that many people base who they are on their job.

“A café waiter who conscientiously does his duty will identify himself totally with his role as a waiter. But this identification is a form of bad faith because it denies the transcendence of human consciousness.”

Although this is still partially true, the personal identity of millennials and Gen Z depends less on their job. They tend to find jobs that match their vocations.

Not many jobs were available in modern times, so individuals settled for a basic job. Now, the labour industry offers many more jobs, providing a way for labourers to find a job that matches their desires.

National identity likewise becomes less prominent in people’s lives. At least for younger people. Digimodernism allows us to consume media far beyond state media (BBC, France television, etc.) and corporately owned newspapers.

Any Western person who reads 3 pages of a history book or investigates geopolitical strategies realises there’s an awful lot to be embarrassed about regarding Western neo-colonial governments. As absurdist Albert Camus states:

“Nationalism is not a cause; it is an effect, a result of a collective neurosis.”

Non-Anglosaxon Gen Zs grow up with English as their second primary language, they consume “YouTube English”, they study abroad, and quickly establish romantic relationships with people with a different passport and native language. Gen Z’s sense of National identity fades.

Another institution that used to give us belongings was the church. As Judith Butler notes:

“The performative dimension of religious practice is a way of inhabiting the norms of religion as part of the constitution of identity.”

The world is going through a secularisation transition at a fast pace. Church attendance plummets, and teenagers associate themselves less with the religious movements their parents raised them in.

When mentioning Judith Butler, sexuality is logically the next step. I already covered how our sexual identities are becoming fragmented. As Michel Foucault points out:

“The notion of a normative sexuality was elaborated and implanted by power in its exercise upon bodies, individuals, and populations.”

If sexual identity is a social construct, then becoming intellectually independent leads to less rigid sexual preferences.

It’s important to state that those on the conservative side of the political spectrum might still hold on to their religion, nationality, gender role, sexuality, and job. However, for progressives, these pillars deteriorate. The further ‘west,’ the more individual societies become (also).

Especially Anglo-Saxon countries have become hyper-personal. People strongly desire to show who they are but can’t rely on the ancient established symbols anymore.

In Europe, people show their personal identity but often do not enforce it upon others. Americans are more aggressive in this manner. They might demand that their environment use their unique pronouns, decorate their cars with a wild array of stickers with bizarre political messages, and give themselves the ‘free speech entitlement’ that goes beyond honourable speech. For some, freedom of speech means freedom to insult.

So, how can people explore and share, in a civilised manner, who they are? The explosion of tattoo culture shows individuals finding alternative forms of self-expression. Sexuality is also used to manifest personal essence. However, individuals crave more tools that support showing personal identity. Spotify Wrapped is one of them — an important one.

Spotify allows you to show who you are!

Not only am I a Dutch sapiosexual cis male with a Radiohead and Bertrand Russell tattoo, but above all, I am an Apocalyptic Permanent Wave Art Rocker.

The social significance of Spotify Wrapped was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.