Generative AI and the long history of artistic automation

The discourse surrounding generative AI in the creative arts is frequently characterised by a sense of historical rupture, a seismic shift unlike any that has come before. Critics often frame the emergence of Large Language Models and diffusion-based image generators as an unprecedented existential threat to the ‘soul’ of human expression, a black swan event that may signal the end of human creative sovereignty. However, when we look back over the history of Western art and technology, it becomes clearer that this anxiety is not a new phenomenon but rather a recurring structural feature of the relationship between human intent and technical innovation. Whenever a new tool emerges that threatens to lower the barrier to entry or automate a process previously governed by arduous manual labour, the established artistic class has responded with a mixture of moral panic, accusations of ‘soullessness,’ and a retreat into essentialist definitions of what constitutes ‘true’ art.

To understand this moment, we must contextualise AI within the history of artistic tools and conceptual shifts, while simultaneously confronting the very real socio-economic and ethical challenges it poses to the creative ecosystem.

Deconstructing the toupee fallacy

Early criticism of generative AI focused on the poor quality of its output. GenAI was not yet a threat because it could not compete with human creative output on quality or believability.

The visceral reaction against early GenAI perhaps stemmed from a hypersensitivity to anomalies that break the illusion of human authorship. The ‘uncanny valley’ describes a revulsion response to humanoid representations that are almost, but not quite, human — a phenomenon observed in robots, animatronics, and increasingly, AI-generated imagery. When an AI image displays six fingers or background incongruities, the viewer immediately labels it as ‘artificial’ and files it away as evidence that AI is easily detectable and low-quality.

https://medium.com/media/eb1dab60a0821709bef73c934e03b92c/href

This creates a false impression of the technology’s overall capabilities through several reinforcing psychological biases. The Toupee Fallacy ensures that only the most noticeable (and typically worst) examples are identified, leading to the belief that AI is inherently detectable and of low aesthetic value. Flawless AI-generated images pass by unnoticed and unquestioned, creating a survivorship bias where only the failures are used to judge the entire category. This mental machinery is further fueled by the uncanny valley, where minor glitches like extra fingers are perceived as deep moral or spiritual failures rather than technical ones. Finally, anchoring bias causes us to fixate on these first ‘bad’ impressions, leading to a resistance to recognizing that these models improve exponentially over time.

This desire for authenticity can be observed in the ‘Invisible CGI’ phenomenon in the film industry. To guard against a backlash toward CGI in cinema, studios frequently market films by claiming “No CGI was used,” despite employing thousands of digital artists to composite scenes, remove safety rigs, and enhance environments. This practice was the subject of a video essay by Jonas Ussing titled “NO CGI” is really just INVISIBLE CGI.

When the CGI is ‘invisible,’ the public credits the ‘practical’ mastery of the director; when it is ‘bad,’ the technology is blamed. Direct experience becomes an unreliable guide to overall quality, as the viewer samples from the bottom of the distribution while remaining oblivious to the top performers.

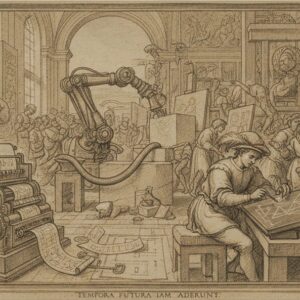

The mechanization of vision: from Vermeer to the silicon brush

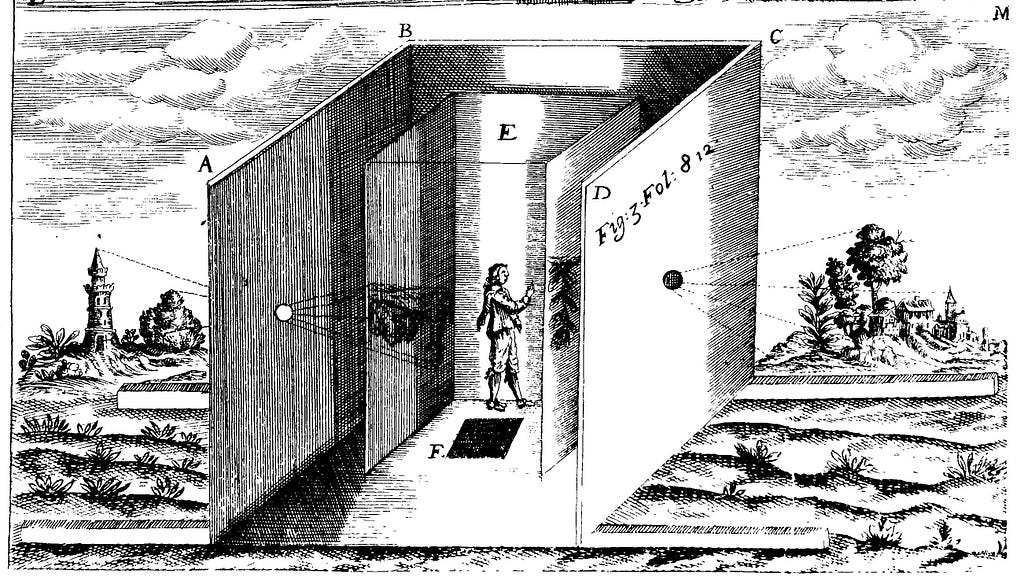

The most persistent argument against GenAI is that it removes the skill of the artist, allowing an amateur to produce high-quality work without the arduous training traditionally associated with mastery. Yet, the history of the Old Masters suggests that ‘skill’ has always been a fluid concept, frequently augmented by hidden technical aids. The Hockney-Falco thesis, proposed by artist David Hockney and physicist Charles Falco, argues that the dramatic rise in naturalism in Western art from the early Renaissance was not due solely to improved talent, but to the widespread use of optical devices such as the camera obscura, camera lucida, and curved mirrors.

Johannes Vermeer is often cited as the archetype of this intersection between art and technology. Analysis of Vermeer’s work reveals ‘circles of confusion’ (pointillés) — optical artifacts that are physically impossible for the human eye to perceive but are characteristic of the ‘imperfect lenses’ of 17th-century camera obscuras. These halations of light on reflective surfaces, such as polished wood or glass, suggest that Vermeer was not ‘eyeballing’ his scenes but was instead ‘transcribing the intensities of light’ projected onto his canvas. Furthermore, the maps hanging in the background of Vermeer’s interiors have been found to be cartographically precise, a level of accuracy that strongly supports the use of a projection device.

The historical trajectory of these aids directly parallels modern AI capabilities. The camera obscura, used by Vermeer and Canaletto, functioned by projecting a real-world scene onto a flat surface for tracing–a process mirrored by modern tools like Stable Diffusion’s ControlNet, which provides a structural ‘sketch’ for a model to fill. Similarly, the camera lucida, a prism device allowing an artist like Ingres to see the subject and canvas simultaneously, parallels current ‘image-to-image’ techniques that transform a base composition into a polished work.

Critics of the Hockney-Falco thesis, much like critics of AI, argue that such tools take away from the greatness of the masters. They maintain that a ‘man of genius’ should not require mere mechanism to achieve realism. However, experiments by Tim Jenison demonstrated that an individual with no formal training as a painter could reproduce a Vermeer-like image using a system of lenses and mirrors available in the 17th century (see Penn & Teller’s documentary Tim’s Vermeer). Jenison’s work proved that Vermeer’s genius was not necessarily found in the manual dexterity of his hand, but in his choice to use technology to capture light in a way that was previously unthinkable.

Critics might argue that Vermeer still required the manual dexterity to apply the paint, whereas AI automates the image creation itself. This highlights the first major ‘shade of grey’: the transition from the handcrafted image to the ‘mechanically assisted’ image is centuries old, but the degree of automation in AI represents a quantum leap that challenges our definition of artistic labor.

The human algorithm: the atelier system and the ‘broken pipeline’

A secondary critique of AI-generated art is that it is ‘dehumanised’ because a machine performs the labour. This argument relies on the romantic myth of the ‘lone genius’ labouring in solitude, an image that has long permeated art history but rarely reflects the reality of major historical commissions. From the Middle Ages through the 19th century, artistic production was organised through guilds and the atelier (workshop) system.

In the studios of masters like Raphael and Peter Paul Rubens, the master functioned more as a creative director than a solo laborer. Raphael presided over a ‘hive of activity’ in Rome with more than fifty assistants. He would provide the ‘cartoons’ (preparatory drawings), while the actual brushstrokes were often executed by pupils who specialized in specific tasks: one might paint the drapery, another the clouds, and a third the architectural backgrounds. The master would reserve for himself only the most critical elements (faces and hands) before signing the final work.

Generative AI functions as a digital extension of this atelier system. The prompter acts as the ‘master,’ handling conceptualisation and curation, while the algorithm acts as the Apprentice or Journeyman, taking on the labour of pigment grinding (data preparation), underpainting, and the execution of complex backgrounds or environmental details. Even the specialists of the Renaissance, who focused solely on flesh or water, find a modern equivalent in Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) models trained to reproduce specific styles or objects with high fidelity.

This system reveals that the ‘master’s signature’ represented a brand and a vision, not necessarily the manual labour of the signer. A painting signed ‘by Raphael’ fetched more than one painted by an unknown journeyman, even if the journeyman performed 90% of the manual labour. Generative AI is the latest iteration of this ‘operational elevation,’ allowing the artist to focus on strategy, decision-making, and leadership instead of routine monitoring or manual repetition.

Yet, here lies a profound contemporary downside: the Junior Hiring Crisis. In the traditional atelier, the apprentice performed ‘grunt work’ (grinding pigments, stretching canvases) in exchange for training and a pathway to mastery.

AI is likely to continue ‘eating the bottom of the career ladder.’ By automating the entry-level tasks that once served as a rite of passage, such as proofreading copy, resizing layouts, or simple coding, the technology is dismantling the traditional apprenticeship model. Recent data indicates a sharp contraction in early-career roles; UK tech companies, for instance,cut graduate roles by 46% in 2023–2024. This broken pipeline suggests that, while AI may offer ‘operational elevation’ for senior professionals, it threatens to leave the next generation without the foundational experiences required to develop professional judgment.

The Luddite misunderstanding: wages, not aesthetics

The term ‘Luddite’ is frequently weaponised in modern discourse to dismiss critics of AI as technophobic. However, the actual history of the Luddite movement provides a more nuanced lens. The original Luddites were skilled textile workers in the early 19th century who objected to the use of machinery to circumvent standard labour practices and undermine the livelihoods of skilled craftsmen.

This historical legacy is reflected today in three distinct ways. The original Luddites of 1811 fought against mechanization as a tool to lower wages and hire unskilled labour, just as modern professional artists fear market saturation by AI-assisted ‘amateurs’. The Neo-Luddite movement of the 20th century expanded this into a philosophy of distrust toward technology as a system of social control, paralleling modern critiques of AI as an ‘alienating’ force that separates art from nature. Finally, the Romantic Movement’s reaction against industrialisation, which celebrated the ‘lone genius’ and ‘sublime nature’, underpins the current ‘soul in art’ argument that AI lacks genuine human feeling.

The Luddites were reacting to a shift from a domestic system, where craftspeople were paid usual price, to a factory system that prioritised efficiency. They were not against technology per se (many were skilled operators); they were against its inappropriate application to lower wages and de-skill the workforce. When applied to the arts, this argument is often misunderstood as a claim that AI makes ‘bad art.’ In reality, the fear is socio-economic: that AI will make cheap art that devalues human labour. Just as the power loom did not destroy the concept of clothing, AI is shifting art from a manual-labor economy to a conceptual-curation economy.

The intellectual divorce: conceptual art and the ‘idea as machine’

The move toward conceptualism in the 20th century fundamentally challenged the requirement for an artist to possess manual technical skills. Marcel Duchamp’s invention of the ‘readymade’ in the 1910s declared that the creative act resided in the choice of the object, not its manufacture. By taking mass-produced objects like a urinal (Fountain) or a snow shovel (In Advance of the Broken Arm) and placing them in a gallery, Duchamp argued that art should ‘serve the mind’ rather than the ‘retinal’ sense. This perspective validates curation as the primary creative act in generative art.

Sol LeWitt famously extended this in 1967, stating: “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art”. For LeWitt, the execution is a “perfunctory affair”. He often provided loose instructions for Wall Drawings that were then executed by assistants. Because the planning and decisions are made beforehand, the artist is free even to surprise himself. This is a verbatim description of generative art, where the prompt acts as the machine that executes the work.

Yoko Ono’s Grapefruit (1964) furthered this by offering ‘instruction pieces’ that could be realised by anyone in their imagination or as an action. She viewed her work as a “recipe for creating reality,” where the artist relinquishes control to the audience. In this framework, the artist is the architect of a possibility space, a role shared by Joseph Kosuth, whose “idea as idea” prioritized the conceptual premise over the physical manifestation.

The modern AI user who explores the ‘latent space’ of a model is the modern heir to this tradition. However, in outsourcing much of our thinking to machines we risk ‘cognitive atrophy.’ While we may increase efficiency, we may lose the creative trial-and-error, the messy process that is essential to creative growth and identity.

The evolutionary remix: jazz, sampling, and the laws of culture

A central ethical argument against GenAI is that it ultimately steals from human artists. The training of AI models requires large-scale ingestion of copyrighted material, often without consent or compensation. Critics describe the process as ‘strip-mining’ human expression. From an ethical standpoint, many creators feel that using their life’s work to build a product that might eventually replace them is a fundamental violation of creative rights.

This assumes that human creativity is ex nihilo (springing from nothingness) rather than being a recursive process of transformation. Kirby Ferguson’s Everything is a Remix philosophy argues that all creative work is built on three pillars: Copy, Transform, and Combine.

This recursive process is visible across various media. In jazz, ‘standards’ serve as a foundational language for musicians to improvise upon, turning popular melodies into exploratory pieces of free jazz. Hip-hop sampling utilizes the ‘copy, transform, combine’ method using turntables and samplers to recontextualize existing beats into new lyrical meanings. Folk music relies on the passing down and altering of melodies over generations to evolve cultural narratives.

The legal landscape in 2025 remains a ‘law unmade.’ While some judges have ruled that AI training is highly transformative and qualifies as fair use, others have rejected this defense when training data is sourced from shadow libraries of pirated books such as LibGen. Futurist Jaron Lanier has proposed ‘Data Dignity’ as a solution, a system that moves away from the black-box model to one where the most unique contributors to a model’s output are acknowledged and compensated via data trusts or ‘Mediators of Individual Data’ (MIDs).

Generative AI represents the digital culmination of a generations-long chain of inheritance. It functions by predicting outcomes based on latent space weights, effectively synthesising billions of artistic ‘quotations’ into a new expression. Roland Barthes’ Death of the Author argued that a text is a “tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture”. AI models are the most sophisticated intertextual looms ever created; they do not ‘steal’ in the sense of removing an object, but rather presuppose and embed prior expressions into new contexts. The liberation of ‘remix thinking’ frees us from the impossible burden of originality and gives us permission to start where others left off. The question of the legal permission to train and make use of all prior links in the chain of inheritance still remains to be solved for now.

The false equivalence: craft vs. art and the amateur’s dilemma

A common critique of AI is that it creates a false equivalence between the professional and the amateur. This debate mirrors the historical reaction to photography. Critics in the 19th century argued that photography was a “thoughtless mechanism for replication” that lacked the “refined feeling” of a human genius. However, the history of art shows that manual craft does not always equal high art.

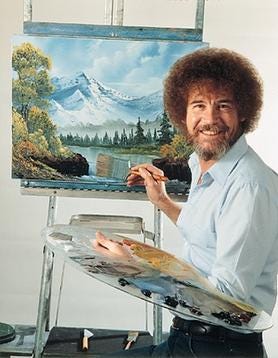

This spectrum of production is well-documented. Bob Ross used an instructional, ‘wet-on-wet’ manual technique to promote a democratic form of craft that, while widely popular, was often excluded from the high art canon. Conversely, Thomas Kinkade utilised an assembly-line factory model where original paintings were digitally transformed into lithographs and ‘enhanced’ by technicians. Kinkade was commercially professional but critically labeled as kitsch.

Prompt engineering via natural language represents a similar shift. While the tool allows high variance, professional output requires the same iterative curation and historical dialogue used by traditional masters who spent years training to guard their status. The tool does not confer professional status; the consistency and depth of the vision do. AI makes everyone an image generator, but becoming an artist still requires the intellectual labor of curation and thematic depth. GenAI has the ability to uplevel creatives at every level of expertise. Yes, it can enable the novice or amateur but when harnessed by the experienced professional it has the potential to lead us to new and exciting horizons.

The unsynthesised truth: synthesisers and the “no bullshit” backlash

The musical world offers a direct historical parallel to the visual AI controversy through the introduction of the synthesiser. In the early 1970s, the synthesiser was viewed with intense suspicion by the rock establishment. The band Queen famously included “No Synthesisers” declarations on their album liner notes up until 1980. This was not a rejection of electronic sound itself, but a ‘commitment to the unsynthesized’ intended to prove their ‘technical prowess’ as musicians who could create complex sounds using only guitars and overdubbed vocals.

Critics of that era, such as those at Melody Maker magazine, often mistook Brian May’s innovative guitar harmonizing for synthesizers. The band used the ‘no synths’ policy as a marketing hook to separate themselves from disco groups and to assert a hierarchy of ‘real’ music over electronic devices.

However, by the mid-1980s, the ulterior motives of even the staunchest holdouts were revealed. Iron Maiden, who had proclaimed “No synthesisers” on their 1983 album Piece of Mind, heavily embraced guitar synthesisers just three years later on Somewhere in Time. They found that the technology allowed them to explore “conceptual themes such as robotics and artificial intelligence” in a way that traditional instruments could not

The transition from “no synths” to “synths as standard” highlights the recurring pattern: technology is initially rejected as a ‘detriment to technical prowess,’ then used as a ‘special effect,’ and finally integrated as a ‘more complex musical layer’. Today’s AI tools are in the ‘special effect’ stage, facing the same backlash that once targeted the Moog and the Fairlight CMI.

Toward a new synthesis of creative agency

The systematically refutable arguments against generative AI in the arts are almost entirely rooted in a misunderstanding of both art history and cognitive bias. When we peel back the layers of Romantic mythology, we find that the history of art is a history of technological integration. Perhaps Vermeer’s genius was his mastery of the camera obscura; Raphael’s genius: his management of a human algorithm; Duchamp’s genius: the conceptual choice that liberated art from the hand.

Generative AI does not represent a break from this tradition, but its most democratic evolution. By acting as a digital atelier, a conceptual machine, and an intertextual loom, AI allows for an ‘operational elevation’ where humans can focus more on the ‘what’ and the ‘why’ of creation, rather than the ‘how’. Physical craft will not disappear, it may even be elevated in value within this new creative context.

The future of art is, as it has always been, intelligent and powered by people. The ‘soul’ of the work resides in the intent of the creator, the curation of the expert, and the historical dialogue that no machine can engage in without a human partner. AI is not the end of art; it is the beginning of the most complex atelier in human history, one that requires us to be more human, not less.

Further reading from UX Collective

- AI-generated art is postmodern art by Michael Buckley

- Uncreative: will AI eat human creativity alive? by Damien Lutz

- Is this the death or dawn of human creativity? by Ian Batterbee

- How AI will elevate human creativity (if we don’t kill it first) by Bethany

References

Works cited

- When Photography Wasn’t Art — JSTOR Daily https://daily.jstor.org/when-photography-was-not-art/

- Luddite | Research Starters — EBSCO

https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/history/luddite - Fooled by Fakes: How the Toupee Fallacy Blinds Us to High-Quality AI Content

https://gregrobison.medium.com/fooled-by-fakes-how-the-toupee-fallacy-blinds-us-to-high-quality-ai-content-a41e6b16b998 - Uncanny valley — Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Uncanny_valley

- No “uncanny valley” effect in science-telling AI avatars — EurekAlert!, https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1079762

- Breaking AI Bias Examples: Machines Reflect Our Human Flaws — Sylvie di Giusto

https://sylviedigiusto.com/ai-bias-examples/ - “NO CGI” is really just INVISIBLE CGI

https://youtu.be/7ttG90raCNo?si=WNoSm2T45AYQS7Iy - Hockney–Falco thesis — Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hockney%E2%80%93Falco_thesis

- Vermeer and the Camera Obscura, Part Two https://www.essentialvermeer.com/camera_obscura/co_two.html

- Did Vermeer Use A Camera Obscura? — Everything Everywhere Daily

https://everything-everywhere.com/did-vermeer-use-a-camera-obscura/ - Camera Obscurities | American Scientist https://www.americanscientist.org/article/camera-obscurities

- The Idea Becomes A Machine That Makes The Art — ksteinfe http://blah.ksteinfe.com/191015/anadol_table_setting.html

- Art Making Machines — Infinite Images — Toledo Museum of Art

https://infiniteimages.toledomuseum.org/essay/coded-nature - Were the Old Masters Really Working Alone? | Serenade

https://serenademagazine.art/were-the-old-masters-really-working-alone-inside-the-renaissance-atelier/ - Atelier — Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atelier - Raphael, Rubens and the Individual Approach — artamaze by Katherine Hilden

https://artamaze.wordpress.com/2012/09/30/raphael-rubens-and-the-individual-approach/ - The Modern Relevance of the French Atelier Tradition — Sotheby’s

https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-modern-relevance-of-the-french-atelier-tradition - Sol LeWitt Art, Bio, Ideas | TheArtStory https://www.theartstory.org/artist/lewitt-sol/

- The AI Renaissance: Reshaping the Workforce and Redefining the Future of Work — Medium

https://medium.com/@kobokala9/the-ai-renaissance-reshaping-the-workforce-and-redefining-the-future-of-work-8a577e6b283d - Luddite — Wikipedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luddite - Why did the Luddites protest? — The National Archives https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/why-did-the-luddites-protest/

- Artisanal Coding Renaissance: Human Craft vs. AI Automation — WebProNews

https://www.webpronews.com/artisanal-coding-renaissance-human-craft-vs-ai-automation/ - Marcel Duchamp & Readymade Art | Definition, Objects & Examples — Lesson — Study.com

https://study.com/learn/lesson/readymade-art-objects-examples.html - Everything You Need to Know About Marcel Duchamp’s Readymades — TheCollector

https://www.thecollector.com/marcel-duchamp-readymades/ - Sol LeWitt on How to Be an Artist — Artsy

https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-sol-lewitt-artist - Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #47 | Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

https://www.museoreinasofia.es/en/collection/research-projects/sol-lewitt/ - Yoko Ono Art, Bio, Ideas | TheArtStory https://www.theartstory.org/artist/ono-yoko/

- Grapefruit (book) — Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grapefruit_(book)

- About Yoko — Fluxus Foundation Archive

https://fluxusfoundation.com/archive/about-yoko-fluxus-foundation-archive/grapefruit-1964/essay-yoko-ono-grapefruit/ - Grapefruit — Idea as Art | Moderna Museet i Stockholm https://www.modernamuseet.se/stockholm/en/exhibitions/yoko-ono/grapefruit-art-as-idea/

- Everything Is a Remix: The Myth of Originality and the Truth About Creativity, inspired by Kirby Ferguson | by Lefteris Heretakis

https://heretakis.medium.com/everything-is-a-remix-the-myth-of-originality-and-the-truth-about-creativity-inspired-by-kirby-94259048fb17 - The Evolution of the Jazz Standard https://www.everythingjazz.com/story/the-evolution-of-the-jazz-standard/

- Part 1: History — Remix Studies http://www.remixstudies.com/abstracts/part-1-history/

- Instigate Sonic Violence: A Not-so-Brief History of the Synthesizer’s Impact on Heavy Metal

https://www.vice.com/en/article/synthesizers-impact-heavy-metal/ - From Harpsichord to Synthesizer and beyond: an introduction to Queen Organology

https://queenvinyls.com/articles/from-harspichord-to-synthesizer-and-beyond-an-introduction-to-queen-organology/

The algorithmic atelier was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.