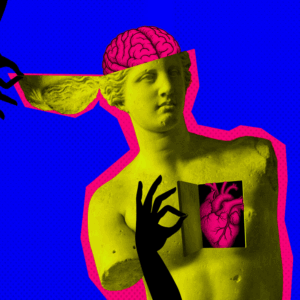

We often shy away from showing our “soft” side at work. But what if that’s our biggest strength.

Heart in brackets.

We can measure our success in many ways. Picking supportive metrics is a big part of a UX designer’s job, so my idea to check how my team was doing wasn’t anything spectacularly unusual.

We approached it from multiple angles: collaborating with colleagues from development teams, conducting research with directors and managers (the “one shelf up” approach), engaging with clients, and providing 360-degree feedback for every team member. I wanted to know how we were seen as a team, as smaller project sub-teams, and as individual people.

It was also the time when we were preparing a big presentation summing up what we’d done so far, the scope of our skills, and the directions for our team’s growth. A team we proudly called Design Queens.

I remember the moment. It was the end of the workday. I was going through the slides the girls had prepared (specifically, Asia), and then right in front of my eyes it appeared — and heart — written in brackets, slipped into my job title: Urszula Kluz, Head (and Heart) of Product Design.

And it wasn’t the KPIs, it wasn’t the certificates, it wasn’t the survey results. Those two little words in brackets were, my friends, the best measure of my leadership I could ever imagine.

No day

It’s been two, maybe three years since that moment. In the meantime, I’ve changed jobs.

It was a Friday. We were wrapping up two intense weeks of work, closing out the quarter for the whole organization. Lidija, the product lead I was working with, an absolute work titan, was crushing it in every meeting. I watched her craft with admiration.

While everyone else was finishing their wrap-ups, I was tinkering away on a little side project: a proposal for a new feature for our product. I knew it was a bit of a “subversive” idea, so in the meantime, I had researched it, prototyped it, and even discussed implementation with the developers.

Proud as a peacock, I peeked into Lidija’s calendar. A half-hour slot. I write: “Lidija, I’ve got a great idea I’d love to tell you about; perfect topic to end a heavy week and step into the weekend with a smile.”

And she replies:

“Ula, today’s my No Day. How about Monday?”

No Day. And that’s when my admiration turned into respect.

Her self-awareness (of herself, of our relationship, of me, of the product) was unique. She knew her current state could affect not only a design decision but also the motivation of a team member and she could manage that consciously. Most importantly, she was honest with herself and with me.

So, my friends: if these two stories have struck a chord with your curiosity and you’d like to know a bit more, read on.

Just please, don’t treat this as a complete leadership guide; that’s not even what I’m aiming for here. Think of it more as the account of someone who’s been there, and with time is now collecting and making sense of her own experiences.

Because yes, you can. You can be the change you want to see in the world*.

Tender and a bit mischievous

Before I built (or maybe it’s more accurate to say: we built) my dream team, I had already worked as a co-editor of a magazine, a curator of group exhibitions, and the head of my own graphic design studio.

And while my work in all those different fields brought more or less spectacular successes (always delivered with flying colors), I would walk away feeling lonely and physically drained.

So when Michał came to me and said: “Ula, what you do, your approach, is brilliant. We need to build you a team,” I didn’t feel like it was a compliment or some big career promotion. Instead, I got chills thinking about sleepless nights and doing all the work for and instead of others.

Luckily, I had enough courage and curiosity to approach building a team differently this time. And no, I didn’t know how to do it. I only knew one thing: it had to be different in every possible way.

And that it wouldn’t be comfortable for me.

Different from me

The time came for my first recruitment. I went through all the CVs myself and invited about a dozen people for interviews. Patrycja was my last interviewee that day.

I asked her to tell me about her favorite project. She shared her screen and for a few seconds, I was staring at a perfect world: a spotless desktop, neatly structured folders, and file names (seriously, not a single new or final_v2 in sight). And in the design files, every layer, every component had a proper name, following a thoughtful naming scheme.

At first, I could barely focus on what she was saying. I was so impressed by her orderliness.

And what I’m about to say is important:

My first instinct was a voice full of insecurity: “You can’t hire her; she’ll expose your messiness. What will she think of you as a leader?”

My second instinct was a voice of reason: “With her, you have a chance to get better.”

And then, for two hours (seriously!), Patrycja spoke passionately about her project, and I silently celebrated the thought of working together.

And indeed, thanks to Patrycja, I developed this internal filter that, during later recruitments, helped me spot subtle hooks in CVs and create interview settings where a person’s unique qualities could shine.

That’s exactly what happened in the last interview I ever conducted… Or actually — heh — Agata conducted it with me 🙂 Because for the entire hour, it was me (and the product owner) answering her questions: about our values and how we put them into practice, about the project and team structure, about the flow of running projects, roles, and responsibilities.

This young woman, who thought of herself as a junior, with those mature questions, outpaced more than one senior in my eyes. By the end of the interview, I didn’t need to ask her a single question. I knew I was talking to someone deeply self-aware.

Building a team by cloning yourself might be easier than working with people who challenge your internal status quo. But it’s precisely those people who help you question your own assumptions and become better in directions you’d never plan for yourself.

In To Succeed Together, We Need to Value What Makes Us Different, Kim Scott explains how homogeneous teams often suppress individuality and innovation, arguing that true progress comes when we “honor one another’s individuality rather than demanding conformity.”

Special ops unit.

This strategy of seeking out “the different one” led us to build a team with a really wide range of skills. It meant we could match people to projects (and projects to people) in a way that met all sorts of demands. And of course, looking at the team and our hard skills, we aimed to grow so that all the key product design skills were covered, while still letting each of us specialise in our own path, and at the same time build a strong shared foundation.

But I’m not going to get into the hard skills here. What’s far more interesting is applying the “different one” principle to soft skills.

That’s especially crucial if you see a designer’s role not just as a “screen drawer,” but as a partner who brings in data and represents the user’s point of view in strategic decisions.

Let’s be honest: in agency work, you rarely get clients with a deep understanding of UX. More often, the whole job of education and communication around UX lands squarely on the designer’s shoulders.

That’s why a diverse team matters so much — it gives you the ability to match the right person to the right people (and here I’m deliberately saying “to people” and not “to the project,” because it’s about the humans who run it).

Here’s how it worked for us:

Patrycja — Fearless Pathfinder

Incredibly independent, proactive, humble, and brave. After just two years on the job, she could run complex projects on her own and stand as an equal partner to Product Owners.

Agata — Rational Explorer

She had research for everything. She could always back up her decisions rationally (right here, right now) even in stressful situations, because she had a huge reservoir of knowledge and knew exactly how to use it.

Asia — Wow Factor Maven

She could solve a visual problem in a matter of moments, leaving everyone’s jaws on the floor. She wasn’t afraid to design live with the client and was irreplaceable whenever a true “wow” effect was needed.

Justyna — Empathic Peacemaker

Her smile and way of being could melt even the iciest hearts. You know the Dunning–Kruger effect? Well, Justyna was a master at talking to that type of client who thought they knew something, and could work her “magic” so they actually ended up learning something.

Pretty impressive, right?

Tools that support growth

You know, there are two kinds of pearls: the perfectly round ones that work great in a classic necklace, and the unique, baroque ones that need the right setting to truly shine. I had the latter. And the setting was: rhythm, structure, and strategy.

Rhythm

Rhythm is a pattern that gives you the comfort of predictability and automates processes, reducing the number of unknowns. Thanks to that, it creates safe conditions for growth and creativity. It’s important for the team to discover its own rhythm and be able to modify it flexibly.

Here’s what it looked like for us (take it as an example, not a recipe): twice a week we had calls to share insights from projects. We often ran a dozen topics in parallel, so democratizing knowledge was a great development tool (for both the team and individual members). It was also a moment to solve ongoing problems before they turned into fires. Every now and then, such meetings turned into knowledge sharing — exchanging thoughts after trainings, readings, or testing new knowledge.

Activities covering a longer period or a larger number of events (e.g. a retrospective after implementing a new workshop formula) we organized as one- or two-day workshops in inspiring places. Sometimes that meant escaping a storm in the mountains, petting dogs, or floating on a lake on inflatable unicorns.

The last element of this rhythm was knowledge exchange with other specializations (e.g. analysts or the Q&A team), thanks to which our solutions were consistent with the rest of the process and stayed in touch with the realities of delivery.

Rhythm gave us daily fluidity, but on a larger scale, we also needed a clear team structure in the organization.

Structure

Our team structure looked something like this:

I was the first point of contact for other departments needing graphic support (marketing, sales, delivery), and at the same time I acted as a filter protecting the team from distractions, so that no one interrupted their work. Knowing the project roadmaps and each designer’s workload, I could efficiently coordinate priorities.

But the most interesting element of this structure was the idea of having two designers in a project, even if the project was small. The first person acted as the lead for about 80% of the time, the second, as support for the remaining 20%.

As you can probably guess, it’s not easy to convince managers and clients to involve two people instead of one in small projects. And that’s where the third element comes in: strategy.

Strategy

Strategy is nothing more than understanding problems and needs, and finding solutions that benefit all parties, while being fully aware of the costs, in the long term.

Take, for example, the case of having two designers on a single project, even a small one, and let’s look at what that meant for each side.

For the designers:

- Faster growth — juniors had someone to learn from, seniors built leadership skills. Exposure to a greater number of projects (even in smaller scopes) sped up experience building.

- Workflow fluidity — it was easier to “switch lanes” between projects and step in where the need was greatest.

- Life — and this is the most important point. When life happened — migraine, heartbreak, or period pain — there was always another person in the project who could take some of the load off your shoulders.

- Creative slumps — everyone has them. They’re easier to handle when you can bounce ideas off someone who knows the context but brings fresh eyes.

For the client:

- Peace of mind — designers often supported Product Owners, so their absence (vacation, illness) carried significant risk. A backup reduced that risk almost without extra financial cost.

- Faster, more effective delivery — the process was less likely to stall, and decisions could be made more quickly.

For the organization:

- Practical standardization across projects — from project workflow to naming conventions in Figma.

- Competency map — real, not wishful, which made career path planning easier.

- Project stability — which translated into financial stability for both designers and the organization.

The cost? The discomfort of having to change the way you think.

All nice and shiny, right?

Only… how do you put it into life when a change in the organization seems big, not about financial costs, but about the discomfort of thinking and acting differently, and the organization itself has little UX awareness?

You need to have a well-mapped set of stakeholders and know with whom and how to talk. I’ll tell it on the example of my leader from a product company, Lidija, because what she did was pure mastery.

In our organization, user testing while creating software was not a standard. That really bothered me; we were working on a specialist application for a very specific professional group, I wanted to be sure it would be intuitive for them, and at the same time I couldn’t look for users outside the company (the project was under NDA). So I asked Lidija for support.

Her move was brilliant: she found in the organization people who not only had the required technical knowledge but could also become ambassadors of the “testing as a standard” approach. They were both managers of other products (hardware and software) and people actively engaged in company life outside the structures. This gave a chance that the topic would spread further.

She talked to them live (important!) and invited them to tests, so they could see with their own eyes that they can be simple, not time-consuming, and cheap. She also added a clear business argument: tests give functionality and usability based on real needs, not wishes. She warned about the cost: just half an hour once a quarter.

The effect? Not only did she help us improve the product (and gave me peace of mind), but she also introduced a change that the whole organization could benefit from. It’s exactly this acting beyond the usual patterns that gives it that mischievous character. Genius.

Tenderness

Awareness, being present, and observing are one thing. It’s only when you add action — or an intentional lack of action — that tenderness happens.

To me, it’s the most important trait of a leader, and it can show up in many forms:

- Care. When Lidija first noticed I’d slipped into my crazy mode (that’s what she called it and, I have to admit, nailed it), she said: “Ula, I can see you’re rushing. Slow down. I don’t want you to burn out.” I think very few employees hear such genuinely caring words from an employer, leader, or client. And she managed to spot it even though we’d only known each other for a few weeks, were almost 900 km apart — and she still reacted with tenderness.

- Silent support. I wanted Patrycja and Asia to see what incredible designers they were in a bigger context. So I suggested they take part in the “Śląska Rzecz” competition (where, by the way, they succeeded). My goal was for them to see their exceptional abilities.

- Freedom to decide. Tenderness is also trust, allowing someone to make different decisions than I would have made myself. That goes for design choices as well as harder situations, like dealing with mobbing or defining your own career path.

This kind of tenderness lets a leader go way beyond standard feedback tools. All the “sandwiches” and 360 feedback methods don’t stand a chance against the feeling of truly being seen and heard.

(I also love how Arvind Mehrotra frames it in How to Drive Better Outcomes with Compassionate Leadership: compassion is not just about empathy, but about concrete actions that boost both well-being and performance. That’s exactly the kind of tenderness I mean.)

When a leader gives space and responds attentively, others start doing the same, first with each other, then with people outside the team. The result? A culture where you can openly talk about being overloaded, ask for help, or admit a mistake before it blows up.

Things that connects

- “Decide.”

- “Thank you.”

- “You nailed it.”

- “Do you need help?”

- “Why didn’t it work? What did I miss?”

- “I need help.”

- “I don’t know, but I’ll find out.”

- “I’m sorry.”

Cost:

Sometimes we work toward the organization’s goals. Sometimes our own. Sometimes what your manager asks for, or the KPIs you agreed on together. And sometimes — something bigger. Something that goes beyond the project, the organization, even time and place. And then, losing it hurts.

On the kitchen board, next to photos of my loved ones, hang notes from the girls. In my backpack, I still carry the Swiss army knife from Lidija. It’s been years, I miss them.

You could call it a cost. I call it a gift.

Because if you miss something, it means it was worth it.

* from Gandhi’s “Be the change you wish to see in the world.”

** the Dunning–Kruger effect is a cognitive bias where people with low expertise tend to overestimate their abilities, while those with greater knowledge often underestimate themselves because they understand the complexity of the subject.

Tender leadership with a bit of mischief was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.