How to translate philosophical theory into practical design principles and responsibility.

The following article introduces an evolving academic framework called Ethical Interface Design, which examines how moral philosophy can guide interface design in the era of emerging technologies. The working site, ethicalinterface.com, presents these ideas through a minimalist, text-focused layout that intentionally prioritizes thought over visuals — a meta-commentary on where design itself may be heading. The framework remains in active development, and thoughtful feedback is welcome.

Society is moving beyond screens into conversational, immersive, and neural experiences, placing designers at the center of the ethical landscape of human–technology interaction. Ethical Interface Design helps designers understand not only the impact of their choices but also the ethical frameworks behind them, exploring:

- How interfaces influence behavior across visual, tactile, conversational, neural, and mixed-reality modalities

- The philosophical roots of Ethical Interface Design — inclusion, autonomy, privacy, transparency, and well-being

- The trade-offs between competing moral frameworks — such as egalitarianism versus meritocracy, or collectivism versus libertarianism — that determine how ethical priorities are balanced in design

- Practical guidance for applying ethics to real-world projects

Ethical Interface Design equips designers to make intentional, responsible choices as they shape the digital world ahead.

Interface Modalities

Every interface mediates the relationship between humans and machines — translating intention into action, and in doing so, shaping how we perceive, decide, and connect. Emerging technologies such as large language models and neural chips are expanding that relationship, blurring the boundary between user and system. As interfaces grow more adaptive and conversational, the very definition of “user interface design” begins to dissolve — replaced by fluid exchanges that merge cognition, language, and computation.

This evolution raises profound questions about agency, inclusion, and moral responsibility — questions explored further in the Ethical Foundations and The Five Pillars of Ethical Interface Design section of this article.

From Command to Conversation

Early computing relied on text-based command-line interfaces — precise but exclusive, accessible only to those fluent in code. The 1980s introduced the Graphical User Interface (GUI), popularized by Xerox PARC and Apple, replacing syntax with icons and windows. This visual paradigm made computing public but also aestheticized control — what you could see, you could do.

As technology spread beyond the desktop, new modalities emerged. Touchscreens redefined tactility. Voice assistants reintroduced conversation. Gesture and neural systems now blur the line between intention and execution. Each step expanded access while also raising new ethical questions about consent, surveillance, and cognitive autonomy.

Types of Interfaces

Interfaces are the boundaries between human intention and digital response. They manifest through the senses and combinations of them — and increasingly through language itself in conversational systems.

- Visual Interfaces → Screens, icons, and layouts that communicate through sight. Examples include smartphone apps, operating systems, dashboards, and AI applications that blend visual and conversational interaction.

- Tactile Interfaces → Touchscreens, trackpads, haptic vibrations, and adaptive textures that make interaction physical. The iPhone’s multitouch screen (2007) made touch the dominant input for a generation.

- Voice Interfaces → Spoken interaction with assistants like Alexa, Siri, and Google Assistant. Generative AI extends this to conversational agents voice mode, emphasizing tone, intent, and context over fixed commands.

- Gesture Interfaces → Motion-based control through cameras and sensors, from the Nintendo Wii (2006) and Microsoft Kinect (2010) to AR/VR hand tracking. They extend interface design into physical space and embodiment.

- Neural Interfaces → Brain–computer links such as Neuralink or medical prosthetics that translate thought into action. These collapse the boundary between user and system, making ethics inseparable from cognition itself.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Hybrid environments such as virtual and augmented reality that merge visual, tactile, and spatial interaction. Examples include Meta Quest, Apple Vision Pro, and AI-powered immersive design spaces.

Every modality encodes a worldview — about who controls interaction, what is considered intuitive, and where agency resides. Ethical Interface Design asks not only how interfaces function, but what kind of human they imagine.

Ethical Foundations

Ethics has always asked how we ought to act. From Aristotle’s pursuit of virtue to Kant’s universal duty and Mill’s utilitarian calculus, moral philosophy has sought to balance intention, outcome, and character. In design, these same questions take form in pixels, code, and policies. Every layout, algorithm, and feedback loop implies an answer to an ethical question — sometimes implicitly, sometimes with intent.

Yet the foundations of ethics are not absolute. Thinkers like Nietzsche, Foucault, and Derrida challenged the idea of universal morality, arguing that ethical systems are shaped by culture, power, and interpretation. From this view, ethics is not a fixed code but a living discourse — one that evolves with our technologies and values. What counts as “good design” may therefore reflect not timeless truth, but the shifting moral architectures of an age.

Philosophical Frameworks

Ethical Interface Design draws from a range of philosophical frameworks that form the foundation of The Five Pillars of Ethical Interface Design. While ethics is contextual, these pillars rest on moral principles widely recognized across contemporary society.

These principles act as guiding coordinates rather than fixed rules, reflecting a shared yet evolving moral landscape. The Five Pillars reveal how ethical tensions emerge when values intersect — the goal is not to eliminate these contradictions but to make them visible, allowing designers to act with clarity and intent.

History shows how one value can override another — privacy may yield to collective well-being during crises, or inclusion may challenge merit-based systems. Ethical interface design highlights these trade-offs, guiding designers toward more transparent and deliberate choices.

Core Ethical and Philosophical Principles

The following list outlines major philosophical frameworks relevant to ethical design. While many other schools of thought exist, these principles form the foundational basis for The Five Pillars of Ethical Interface Design.

- Collectivism → A moral and political philosophy that prioritizes the needs, goals, and well-being of the group over individual interests. It emphasizes cooperation, shared responsibility, and social interdependence as essential to human flourishing.

- Communitarianism → A perspective emphasizing community, shared values, and social responsibility in shaping moral and political life. It critiques excessive individualism in liberal thought.

- Egalitarianism → The view that all individuals deserve equal moral consideration and that social and economic inequalities require justification. It emphasizes fairness, equal opportunity, and the reduction of arbitrary privilege.

- Kantian Ethics → A deontological moral theory grounded in reason and autonomy. It holds that moral action arises from adherence to universal moral laws derived from rational duty.

- Liberalism → A political and moral philosophy that upholds individual rights, freedom of choice, and consent as the basis of legitimacy. It limits interference by the state or others in personal domains.

- Libertarianism → A philosophy centered on individual liberty and minimal external control. It values personal autonomy, voluntary exchange, and limited government intervention, often resisting collective mandates or welfare-oriented design.

- Meritocracy → The belief that rewards and positions should reflect individual talent, effort, and achievement rather than social status or inherited privilege. It values ability and contribution as the basis for distribution.

- Pragmatism → A philosophical movement that evaluates ideas and actions by their practical effects. It privileges usefulness and results over strict adherence to principles or absolute truth.

- Utilitarianism → A consequentialist theory asserting that moral value depends on outcomes, with the best action being the one that maximizes overall happiness or minimizes suffering for the greatest number.

- Virtue Ethics → A moral framework emphasizing the cultivation of moral character and the pursuit of virtue. It focuses on traits such as honesty, integrity, and wisdom as the foundation of ethical behavior.

Toward an Ethical Interface

As we move into an era defined by artificial intelligence, automation, and neural integration, ethics becomes both more complex and more urgent. Interfaces now operate at cognitive and emotional levels once considered private. The goal of Ethical Interface Design is to preserve human dignity within this expanding field of influence.

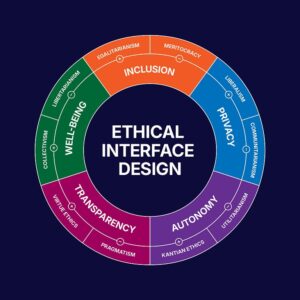

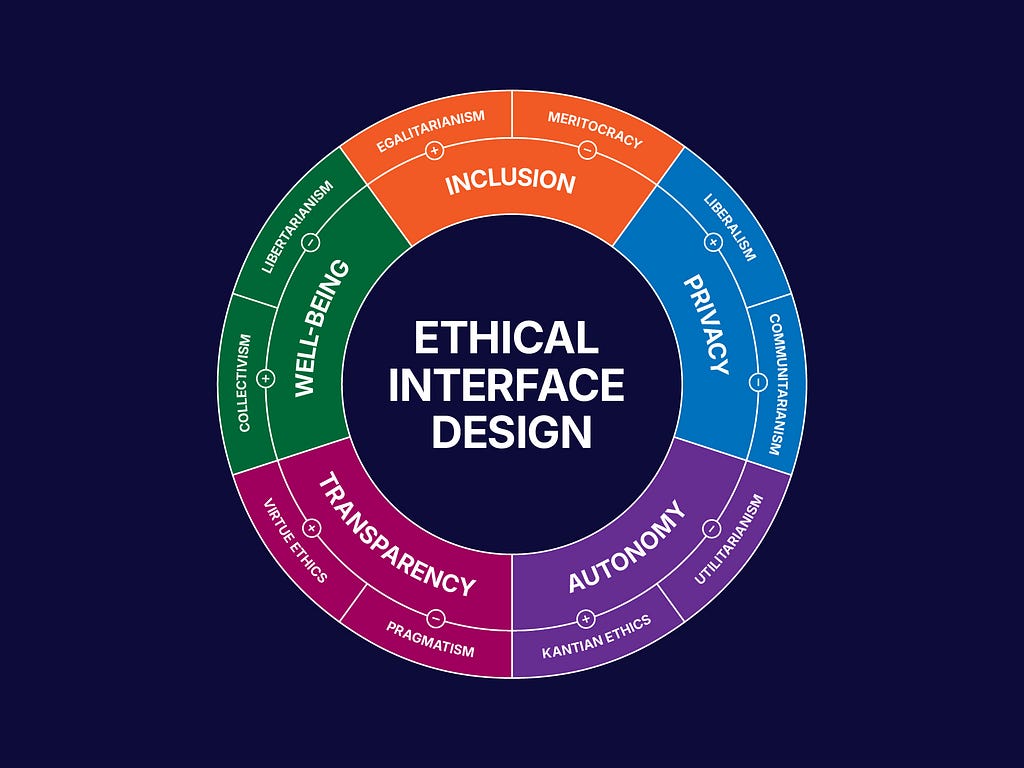

The Five Pillars of Ethical Interface Design

The Five Pillars of Ethical Interface Design are built on established ethical principles and common and emerging interface modalities. Together, they reveal how moral values manifest across different modes of interaction — and how every ethical choice involves trade-offs that designers must navigate responsibly.

To learn more, review the principles in detail below. For a concise overview, refer to the summary diagram.

Inclusion

Inclusion ensures that interfaces welcome, represent, and empower people across abilities, cultures, and contexts. It rejects design that privileges one type of user at the expense of others and treats accessibility not as accommodation but as design integrity. An inclusive interface assumes difference as a constant, not an exception.

Examples Across Modalities

- Visual Interfaces → Support diverse visual and linguistic literacies through adjustable type scales, high-contrast modes, and culturally inclusive iconography.

- Tactile Interfaces → Design haptic feedback and physical controls that accommodate varied dexterity and sensory abilities, ensuring equitable interaction.

- Voice Interfaces → Train recognition systems on global accents, dialects, and speech patterns to prevent bias toward dominant languages.

- Gesture Interfaces → Calibrate motion detection for diverse ranges of movement, body types, and physical capabilities instead of a single “ideal” gesture model.

- Neural Interfaces → Build adaptive systems that account for neurodiversity, cognitive variation, and comfort levels in signal interpretation.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Configure AR and VR environments to support varied sensory sensitivities, spatial perception, and physical comfort across users.

Underlying Philosophy

Rooted in Egalitarianism. The core claim is moral equality — like cases should be treated alike unless a relevant difference justifies unequal treatment. In design terms, capability differences, cultural background, and context are relevant inputs to equalize effective opportunity, not reasons to exclude.

Contrasting Philosophy

Meritocracy links reward to demonstrated talent, effort, or productivity, appealing to fairness through performance. In design, this logic supports optimizing for “power users” or “high-value segments” to maximize efficiency and impact.

Ethical Tension: Equality vs. Merit

Design Focus → Design for accessibility and difference as defaults while recognizing merit, balancing equality with performance.

- Adopt accessibility guidelines (WCAG, WAI-ARIA) as creative constraints.

- Use participatory methods to include marginalized users in testing and feedback.

- Offer personalization — contrast, input method, motion sensitivity, voice settings — without stigma.

- Audit datasets, prompts, and imagery for cultural or algorithmic bias.

- Frame inclusivity as an innovation driver that benefits all users.

- Provide “power features” as additive layers, not the default path.

- Evaluate efficiency metrics for the whole user base, not just the fastest quartile.

Autonomy

Autonomy protects the user’s capacity to think, choose, and act without manipulation or coercion. In interface design, it means preserving agency — giving users real control over what they see, share, and decide.

Examples Across Modalities

- Visual Interfaces → Empower users to manage visibility and consent through clear privacy controls, opt-in dialogs, and transparent data-use indicators.

- Tactile Interfaces → Provide physical controls, such as undo buttons and emergency stops, that let users reverse or interrupt actions on their own terms.

- Voice Interfaces → Require explicit verbal control over actions, ensuring conscious intent over automated interpretation.

- Gesture Interfaces → Design gestures that distinguish deliberate intent from incidental movement, preventing unintended triggers.

- Neural Interfaces → Secure informed consent and allow opt-out before interpreting or predicting user intent from neural signals.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Give users control over spatial permissions, tracking boundaries, and data sharing within AR and VR environments.

Underlying Philosophy

Grounded in Kantian Ethics. People must be treated as ends in themselves, not as means to collective goals. Ethical action respects rational self-rule, even when doing so conflicts with collective well-being. Favor transparent choices, meaningful consent, and reversibility over efficiency or mass benefit.

Contrasting Philosophy

Utilitarianism values the greatest good for the greatest number. This approach may favor streamlined decisions, the removal of risky options, or persuasive defaults to maximize collective well-being and system efficiency.

Ethical Tension: Freedom vs. Welfare

Design Focus → Preserve informed choice while allowing limited, transparent guidance that prevents harm without coercion.

- Treat informed consent as ongoing and contextual.

- Provide granular settings for automation and data sharing.

- Default to privacy-preserving choices.

- State clearly where automation begins and ends.

- Eliminate dark patterns and manipulative urgency cues.

- When nudging for welfare, disclose the nudge, show the rationale, and offer a one-tap opt-out.

- Provide escape hatches (undo, exit, manual override).

Transparency

Transparency concerns the integrity of information shared between humans and systems. It requires honesty, disclosure, and authenticity so that what is shown aligns with what is real. It provides the truthful foundation necessary for understanding, accountability, and rational choice.

Examples Across Modalities

- Visual Interfaces → Present data truthfully through accurate charts, clear sponsorship labels, and visible indicators of AI-generated or manipulated media.

- Tactile Interfaces → Provide feedback that reflects the true system state, distinguishing between successful actions, errors, and pending responses.

- Voice Interfaces → Disclose when users are interacting with non-human agents and summarize what information is recorded or retained.

- Gesture Interfaces → Notify users when motion data is being tracked, interpreted, or stored to maintain awareness of system observation.

- Neural Interfaces → Distinguish which neural signals can be measured versus which should be, clarifying how thought-related data is interpreted and used.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Display clear boundaries between simulated and real elements, including visibility into what is recorded, shared, or AI-generated within AR/VR environments.

Underlying Philosophy

Draws on Virtue Ethics. Honesty and truthfulness appear as reliable presentation, avoidance of deception, and willingness to disclose limits. Interfaces operationalize these traits via faithful visualizations, provenance signals, and candid explanation of uncertainty.

Contrasting Philosophy

Pragmatism values what works over what is strictly true. It treats clarity and usefulness as higher goods than full disclosure, accepting that some truths may be simplified or deferred when they hinder progress.

Ethical Tension: Truth vs. Utility

Design Focus → Reveal truth and uncertainty clearly and in context, maintaining usability and trust.

- Disclose algorithmic involvement in rankings and outputs.

- Make consent and data flows comprehensible in context.

- Expose uncertainty and known limitations.

- Align copy and feedback with actual system behavior.

- Design clarity as a user benefit, not just compliance.

- Use layered explanations: short, then expandable detail — never hide conflicts of interest.

- Avoid “spin” — simplify presentation without sacrificing truth.

Privacy

Privacy safeguards the boundary between the individual and the system. It upholds user control over information, attention, and identity — defining the conditions under which data is observed, shared, or stored.

Examples Across Modalities

- Visual Interfaces → Provide clear permission settings, visible tracking indicators, and accessible private modes that let users manage visibility and data exposure.

- Tactile Interfaces → Incorporate hardware shutters, physical switches, and tactile indicators to give users direct control over sensors and device activity.

- Voice Interfaces → Include audible or visual cues when recording begins, and enable quick, in-flow deletion or redaction of captured speech.

- Gesture Interfaces → Capture movement data only upon explicit initiation, ensuring gestures are recorded intentionally rather than passively monitored.

- Neural Interfaces → Protect sensitive neural data through local processing, encryption, and consent-based access to signal interpretation.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Allow users to define spatial privacy zones and control when spatial mapping, camera feeds, or biometric data are shared.

Underlying Philosophy

Informed by Liberalism. Individuals possess rights to personal domain and consent that constrain collective or commercial interests. Privacy functions as a precondition of autonomy by preserving mental space for deliberation, identity formation, and dissent.

Contrasting Philosophy

Communitarianism prioritizes common goods and may endorse broader sharing for safety, coordination, or solidarity. Legitimate community aims must be balanced against the standing claim of individuals to control access and use of their data.

Ethical Tension: Autonomy vs. Solidarity

Design Focus → Protect dignity through consent and control while permitting ethical data sharing for genuine collective benefit.

- Practice data minimization.

- Show what’s shared, why, and for how long — without fatigue.

- Make controls accessible, contextual, and reversible.

- Process data on the user’s device whenever possible — use cloud storage or computation only when essential and clearly justified.

- Frame privacy as trust that enables participation.

- For “common good” uses, require aggregation, anonymization, purpose binding, and expiry by default.

- Provide opt-out mechanisms for any data pooling or sharing when feasible — document non-optional cases.

Well-Being

Well-being asks whether technology supports human and ecological flourishing — psychological, social, physical, and environmental. It favors sustained clarity, balance, and restoration over compulsive engagement, overuse, or unsustainable resource demand.

Examples Across Modalities

- Visual Interfaces → Design calm visual hierarchies, offer dark or focus modes, and adjust color temperature or brightness over time to reduce eye strain and fatigue.

- Tactile Interfaces → Use haptic cues to encourage rest, posture shifts, or mindful breaks, supporting physical comfort and recovery.

- Voice Interfaces → Employ tone and pacing that convey calm support without emotional manipulation or artificial empathy.

- Gesture Interfaces → Encourage healthy movement through interaction patterns that counter sedentary use and promote active engagement.

- Neural Interfaces → Adapt cognitive pacing and information density to match user comprehension and prevent overload or fatigue.

- Mixed Reality Interfaces → Balance immersion with grounding cues, allowing users to pause, recalibrate, or exit experiences to protect mental and physical well-being.

Underlying Philosophy

Anchored in Collectivism. Well-being is measured by the health of the collective — how design supports shared welfare, mutual dependence, and the long-term sustainability of both human and ecological systems. Design choices emphasize cooperation, community benefit, and responsibility for collective outcomes over purely individual gain.

Contrasting Philosophy

Libertarianism prioritizes individual freedom and self-determination, often resisting design constraints that guide or limit user behavior for the sake of collective good. From this view, interventions that promote well-being — such as limiting usage or prompting rest — can be seen as paternalistic, infringing on personal autonomy even when intended for protection or benefit.

Ethical Tension: Welfare vs. Freedom

Design Focus → Foster flourishing and reduce harm without violating autonomy or moral boundaries.

- Replace engagement KPIs with well-being metrics: satisfaction, balance, trust, recovery.

- Use persuasion for healthy habits, not compulsion.

- Add protective friction: time limits, focus modes, optional pauses.

- Assess long-term emotional and cognitive effects of tone, color, and loops.

- Test for calm, clarity, and self-perception, not only task completion.

- Offer well-being prompts as configurable aids with clear off switches.

- Decouple core utility from compulsive loops (infinite scroll, variable rewards).

Design for the Future

Design for the future means translating moral philosophy into tangible choices that shape how people live, work, and connect. Ethical Interface Design and the Five Pillars framework were developed by Michael Buckley to help designers approach emerging technologies with awareness and accountability. The framework offers a structured method for aligning design decisions with ethical intent — bridging creativity, usability, and human values.

Collaborate & Connect

If you’re interested in exploring Ethical Interface Design further — or would like to discuss a speaking engagement, workshop, or collaboration — please get in touch. Reach out at hello@ethicalinterface.com

Services

- Speaking & Workshops: Presentations on Ethical Interface Design, media literacy, and design philosophy.

- Consulting: Guidance for teams creating transparent, inclusive, and autonomy-driven digital experiences.

- Collaboration: Academic, research, and publication partnerships on ethics and emerging interface systems.

Together, we can shape technology that serves human values.

About the Author

Michael Buckley is a Professor at Seton Hall University, where he teaches UX/UI design, web coding, and graphic design. With nearly two decades of experience as a creative director, brand strategist, and UX/UI engineer, his work has been recognized across healthcare, publishing, and technology for its innovation and social impact.

Don’t miss out! Join my email list and receive the latest content.

Guiding the future of ethical design was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.