Designing with curiosity and criticality for responsible outcomes.

*Trigger Warning* suicide.

“Don’t move fast and break things when it comes to our kids.” These were the words from the mom of 14 year-old Sewell who ended his life after an ongoing chatbot conversation on Character AI. The story is heartbreaking on so many levels. It’s a story of a boy who died too young. It’s a story of a mom grieving her loss. It’s a story of loneliness. But it is also a story about how our current design and tech practices are causing irreversible harm.

For many years, the innovation, tech, and design industry has been guided by the motto “move fast and break things”. It’s been a way for us to try out new ideas quickly. It’s been a way for us to uncover new possibilities.

In theory, the idea makes sense. We want to limit the investment up front in order to ensure that we don’t head too far down the wrong path. It helps us make sure that we are solving the right problem.

However, when the things breaking are people, communities, and the planet, we must ask ourselves: at what cost?

Unintended consequences: Design today is causing harm

Over the past few years, I’ve realized that our work as designers is not just to spot and solve problems. It’s also to make sure we don’t create them. The story of 14 year-old Sewell is one example of an unintended consequence when new technology enters the market without considering what could go wrong. We don’t have to look far to find other examples.

The way we design our buildings is creating uninhabitable cities. The applications meant for connection are contributing to an expanding mental health crisis. And brands promise to “open happiness” while contributing to the rise in diabetes and related health problems.

As we find ourselves in the interrelated crises of climate change, food scarcity, energy depletion, global poverty, and loss of meaning (intersections often refered to as the Polycrisis), it’s easy to see that we cannot continue with design as usual. Moving fast and breaking things is no longer acceptable and as designers, we need to start considering both possibilities and the responsibilities we hold.

DesignShift: From how might we to at what cost

I believe that “Good design is a dance between curiosity AND criticality.” In design thinking, we use the question “how might we” to encourage opportunities through curiosity. In the course Hello Design Thinking IDEO explains: The “how” is solutions-oriented, the “might” encourages optimism, and the “we” is collaborative. Having worked at IDEO, How Might We is close to my heart. I love the openness it brings. Many times, it’s helped me step out of my perfectionistic nature, identify problems and dream up new solutions through a curious lens. I love that.

However, throughout the years of trying to innovate in a responsible way, I’ve also come to realize something critical and that is as often as we ask “how might we” we also have to ask “at what cost.” Design can heal but it can also harm. These complementary questions create a necessary tension that leads to more responsible outcomes.

An tool for equitable outcomes

So, how do we really balance these tensions of possibility and responsibility? In May 2025, I hosted a workshop at the Berlin Design Week where we put this tension into practice through an interactive activity. It was a way to invite the audience to dance with the possibilities and the responsibilities of design, and I invite you to do the same through an exercise.

This activity is designed for you to reflect deeply and thoughtfully on an idea, project, or product you’ve worked on or are considering.

- Start by imagining something you have created, contributed to, or are thinking about developing. Write it down or keep it in your mind.

- Take a piece of paper or any other tool you want to use for notes. Create one section for “How Might We” and one section for “At What Cost”.

- Review the questions below and start answering each of the questions from a possibility and responsibility lens.

Take your time with each prompt. This is your opportunity to think critically and honestly, helping you make more informed and responsible choices.

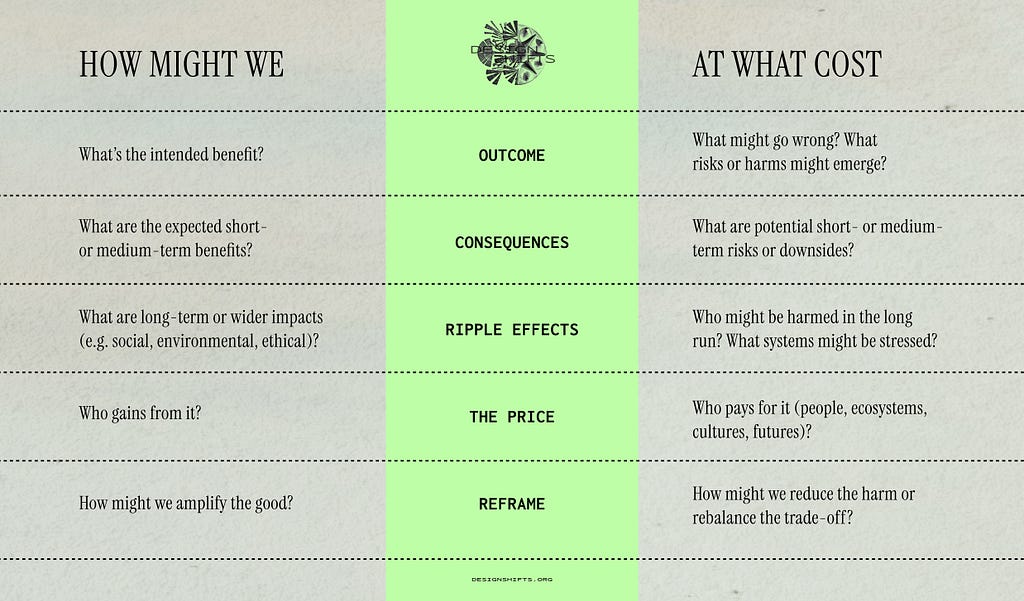

How might we (Exploring possibility through the lens of curiosity)

- Outcome: What’s the intended benefit?

- Consequences: What are the expected short- or medium-term benefits?

- Ripple effects: What are long-term or wider impacts (e.g. social, environmental, ethical)?

- The price: Who gains?

- Reframe: How might we amplify the good?

At what cost (exploring responsibility through the lens of criticality)

- Outcome: What might go wrong? What risks or harms might emerge?

- Consequences: What are potential short- or medium-term risks or downsides?

- Ripple effects:Who might be harmed in the long run? What systems might be stressed?

- The price: Who pays for it (people, ecosystems, cultures, futures)?

- Reframe: How might we reduce the harm or rebalance the trade-off?

By asking yourself “How Might We” along with “At What Cost” you will gain clarity on who stands to gain or lose, what trade-offs might exist, and how you could amplify positive impacts while reducing negative ones.

As designers, we are responsible for the intended and unintended consequences of our work. Or like Kate Holmes says in the book Mismatch — How inclusion Shapes design, designers should be “making intentional choices, over risking an unintentional harm.”

Should we? Sometimes the best design is no design.

It’s profoundly challenging to tell a client “no,” especially when they’ve invested years of work and resources into a project. The traditional client-designer relationship often positions the paying client as our primary focus — we’re hired to execute their vision, not question it. However, I believe designers have an ethical responsibility to look deeper and expand wider. Our ultimate goal should be to serve the people who will use our designs. We have a responsibility towards them first and foremost. And then of course, we have a responsibility towards the planet that supports us all. Ideally, clients goals and the needs of people and the planet align. In the end, clients make solutions for people and we all need the planet to survive, but this is not always the case.

This perspective aligns with John Thackara’s critique of the risk management industry in his post Oil-Powered Thinking. He observes that despite the proliferation of risk management consultants, “the world is not, to put it mildly, a safer place.” Why? Because these consultants “do not, by and large, advise their clients not to take risky actions. On the contrary: their job is to make it possible for their client to take those actions anyway — but to make sure someone else pays for any negative consequences.”

This pattern repeats across industries: someone else — often the most vulnerable — pays for the consequences of our innovations and good intentions. We see this clearly in the sustainability sector, where electric vehicles may reduce carbon emissions in wealthy countries like Sweden, while the environmental and social impacts of mineral extraction are materialized in communities and climate disasters in distant countries. Sometimes we’re simply unaware of these consequences, but often our focus on short-term profits blinds us to long-term impacts.

A new, more responsible design future

Today, we’ve explored the unintended consequences of rapid innovation, the ethical responsibilities of designers and entrepreneurs, and ways we can account for harm before it happens.

As designers and creators, we stand at a critical crossroads. Our work has the power to transform lives, but also the potential to cause unintended harm. The question isn’t whether we should innovate, but rather how we can innovate responsibly.

The story of Sewell reminds us that the stakes are high. When we design digital experiences, products, or services, we’re not just creating things — we’re influencing lives, cultures, and behaviors. This is a privilege to design and something that we should not take lightly. The responsibility that comes with this power demands that we slow down, ask harder questions, and develop the courage to say “no” when the potential for harm outweighs the benefits.

I believe in a design future where like Arturo Escobar writes in Designs for the pluriverse:

“Might a new breed of designers come to be thought of as transition activists? If this were to be the case, they would have to walk hand in hand with those who are protecting and redefining well-being, life projects, territories, local economies, and communities worldwide.”

As we navigate interconnected crises — from climate change to mental health, from systemic discrimination to technological harm, let’s commit to this balance of curiosity and criticality. Let’s create solutions that don’t just solve problems, but do so without creating new ones. And let’s listen to Sewell’s mom and stop moving fast and break things when it comes to our kids (and anyone else for that matter). Let’s look at problems both with curiosity and criticality, asking not just “How might we?” but also “At what cost?”

Additional tools for harm assessment:

- MIT AI Incident Tracker

- Consequence Scanning — an agile practice for responsible innovators — doteveryone

- Responsible Engineering Overview — Azure Architecture Center | Microsoft Learn

- A framework to help you account for unintended consequences.

- Persuasive Backfiring: When Behavior Change Interventions Trigger Unintended Negative Outcomes

- Unintended Consequences: Some readings on art, design, and gentrification.

- Consideration Cards — < DESIGN ETHICALLY >

- Futures Wheel — UNGP — Foresight Project

- Stories for Life

From “how might we” to “at what cost” was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.