Why government keeps forcing uncertainty through systems designed for stability — and what an alternative might look like

In a previous article, I argued that the UK government is structurally unfit for uncertainty — taking 21st-century challenges, evaluating them with 20th-century tools, and responding within 19th-century institutions — built for a different time, and for different kinds of problems. And, if Labour’s mission-driven government is to mean anything in reality, the civil service needs a new grammar of everyday decision-making: one that treats uncertainty as navigable, frames choices in terms of risk and opportunity rather than cost and control, and builds learning into how problems are defined and acted upon.

This piece starts where that argument ends, asking what a different architecture for decision-making might look like when uncertainty is high — and stability still matters. To answer it, this article explores why existing innovation efforts repeatedly collapse back into business-as-usual routines, before setting out an alternative, overlaying architecture for decision-making under uncertainty: one built on the premise of strength without weight and dynamic learning at its core.

Beyond the waterfall state

To be clear, the answer is not to burn everything down and start again. It points in a very different direction from the chainsaw, scorched-earth approach of the Elon Musks of the world. As Andy Knight reminded me, most of what government does is stewardship — and that function is indispensable. It depends on stable, convergent, waterfall prediction policymaking. It is what keeps the lights on. Literally.

But the architecture that underpins stability is not the architecture that enables transformative change. Keeping the lights on today matters — but so does ensuring they stay on in the future. Missions, systems change, and early-stage sense-making require something different: space for divergent creativity, structured exploration, and collective judgement. This is the foundation for a state that is able to work with uncertainty rather than suppress it — what Kattel, Drechsler, and Karo describe as agile stability: the capacity to generate new directions while maintaining long-term institutional coherence.

The problem is that we continue to run all forms of decision-making — certain and uncertain — through the same architecture inherited from a New Public Management era, an architecture built on the assumption that if you press a button, you know something will happen — as if governing were a computational task with bounded rationality rather than a socio-technical one. While this logic may work tolerably well for stewarding stable systems, organisations — and the world around them — are not computers. When uncertainty is high and judgement, learning, and creativity matter most, this type of computational “bounded rationality” repeatedly fails (See: Statecraft for the 21st Century) leaving us with a hollowed-out version of what Charles Lindblom once described as “muddling through”: not pragmatic adaptation, but institutional drift in the face of uncertainty.

James Plunkett has suggested that this traps government in a kind of “local maximum” able to improve what it can already see, but unable to perceive or reach a wider landscape of possibility. Sophia Parker extends this argument, noting that when institutions are caught “between worlds,” the familiar tools of optimisation cannot open up a larger reality — they only make us better at navigating the status quo.

“A local maximum is a place where everything you try seems to make things a bit better, but nothing you try can make things fundamentally different” — James Plunkett

This is precisely why the re-emergence of mission-oriented and responsible approaches to policymaking — used here as an umbrella for systems thinking, futures thinking, user-centred design, agile methods and other exploratory practices — has put the limits of the administrative system in the spotlight. Instead of becoming a routinised way of organising systemic change, missions — and the transformative methods attached to them — repeatedly collapse back into incrementalism and business-as-usual routines when they are forced through an architecture built for stability.

See Kattel & Mazzucato on why missions struggle to make an epistemic turn within existing bureaucratic logics, Demos Helsinki’s “Missions for Governance” on how missions constrained by current mechanisms tend to produce only incremental improvements.

So, if the architecture is the limit, the question becomes not how to replace the existing system (we rely on its stability more than we admit), but how to create an overlaying architecture that can be activated when uncertainty is high and when public value depends on exploration. Geoff Mulgan refers to this type of bureaucracy as having “strength without weight,” the ability to use institutional power without the bureaucratic drag that stifles learning — enabling decision-making supported by intelligence, curiosity and adaptability, rather than the machinery of implementation and control.

The capabilities the state needs to work under uncertainty

Any discussion of a second, more agile organisational architecture for navigating uncertainty and producing public value must begin with capability. Not whether an organisation has the right structures on paper, but whether it can learn, coordinate, and adjust as conditions change. Working under uncertainty — and delivering any form of transformative, systemic change — requires a different way of thinking about both public value and the organisational capabilities that sustain it.

First, public value cannot be treated only as an outcome delivered at the end of a policy process, or as a means-to-an-end justified through appraisal. As Mark Moore argues, it is both an outcome and something produced through the policy process itself. Under conditions of uncertainty, the quality of these processes is not incidental; it is constitutive of public value, shaped across an organisation’s mission, sources of legitimacy and operational capacity. Treating value as both an outcome and a process provides a practical way to judge whether particular actions are improving a situation and are worth their costs.

This shifts attention to the dynamic capabilities embedded within public organisations: the capacities that allow institutions to sense change, coordinate across boundaries and deliberately reshape resources and priorities as the environment shifts. These are not specialist innovation skills or isolated tools, but foundational capabilities — central to public value management — that determine whether an alternative decision-making architecture can function at all.

This aligns closely with work on Human Learning Systems, which frames outcomes as emergent properties of complex systems and treats learning, adaptation and relationship-building not as phases of reform, but as the core work of public management under complexity.

This is where the Institute of Innovation and Public Purpose’s work on dynamic capabilities is particularly useful. For this discussion, it helps clarify both what decision-making under uncertainty requires and why so many innovation efforts struggle to influence practice. Three dynamic capabilities are especially relevant here:

- Sense-making: the ability to scan an environment, surface weak signals, and develop shared interpretations of what is happening and why. This is not about better forecasting or more data, but about collective orientation when evidence is partial, contested, or evolving.

- Connecting: the capacity to coordinate across organisational, disciplinary, and sectoral boundaries. Under uncertainty, no single team or function holds the full picture. Effective decision-making depends on integrating different forms of knowledge and negotiating trade-offs across silos that were never designed to meet.

- Shaping: the ability to reconfigure priorities, resources, and routines in response to what is being learned. Without this capability, insight accumulates but decisions remain locked in — learning exists, but it has no leverage.

Taken together, these capabilities frame public value as something produced through decision-making itself (or “strategic management” if you would rather). How problems are framed, whose knowledge is included, when commitments are made, and whether learning is allowed to alter direction all shape whether public value is created — or quietly eroded.

Why innovation efforts collapse back into business as usual

The difficulty is not a lack of innovation activity, it’s where that activity sits relative to how decisions are actually made. Uncertainty demands dynamic capabilities such as sense-making, connecting, and shaping. Yet, most public-sector decision-making architectures are designed to steward stable systems, not to navigate contested, evolving or genuinely new ones. This creates a structural mismatch where even when teams attempt to work differently — through experimentation, design or mission-led approaches — the surrounding architecture pulls decision-making back towards certainty.

Public Digital’s The Radical How illustrates this issue. In the dominant waterfall model of policymaking, the most consequential decisions are made upfront — precisely when uncertainty is highest — while learning arrives later, once direction has already been fixed. The process follows a familiar pattern: Write policy → guess requirements → procure IT systems → Inflict on users at scale → operate indefinitely.

Seen through this lens, learning is systematically pushed downstream, when its capacity to shape outcomes is weakest. Innovation efforts are not failing because they lack ambition or quality, but because they are layered onto an architecture that is structurally hostile to uncertainty.

This pattern repeats across governments. New methods are introduced, capabilities are developed, and insights are generated — but only after the moments when direction is set, resources committed, and alternatives foreclosed. The result is activity without leverage: innovation that is visible and energetic, but ultimately powerless.

Three examples help bring this structural mismatch to life.

- Policy Labs

Policy labs are among the most significant attempts to embed learning into policymaking through user-centred and systems perspectives. They are designed to intercept policy ideas early and improve decision quality (see Anna Whicher on the evolution of Policy Labs in the UK). In capability terms, labs are particularly strong at sensemaking in many ways. A large part of my own work is surfacing lived experiences, identifying risks and challenging the assumptions of policy teams while at the same time bringing together multidisciplinary actors who would not normally work together and creating relational infrastructure across policy and delivery siloes.

The problem, however, is not what labs do, but when they are able to do it. Within the existing decision-making architecture, the moments when assumptions can genuinely be challenged are tightly constrained. Policy labs rarely control the decision gates where commitments are made, budgets locked in or political capital spent. Their insights enter policy processes already moving toward closure. Learning exists, but it arrives downstream of power.

As a result, insight is absorbed rather than acted upon — often filed away in the proverbial “policy drawer” while assumptions remain untested. Labs generate understanding, but without authority to reopen decisions, that understanding struggles to shape outcomes.

2. Technology-centric or challenge-driven funding

Technology programmes and challenge-driven funds apply shaping pressure differently. They create momentum around emerging technologies and capabilities, directing attention, investment, and experimentation towards what might be possible. In doing so, they generate valuable insight into technical feasibility and future options — often through pilots, prototypes, and partnerships that test new approaches in practice.

This activity frequently supports sense-making as well — imagining new uses of AI, automation, or data at scale, and expanding the perceived solution space.

The problem is not the quality of this learning, but its position in the decision-making system and who it involves. Insights generated through challenge funds rarely travel upstream into everyday policy work. Policy teams struggle to access or apply what has been learned — not through resistance or lack of interest, but because there are few institutional pathways for the diffusion of knowledge.

As a result, innovation happens around the policy system rather than within it — shaping the environment without reshaping the decisions that govern it. Insight accumulates, but without leverage where it matters most (see my note on the frustration of AI pilots here).

3. Generalist training, hackathons and experimentation initiatives

Perhaps the most compressed illustration of the problem comes from generalist training programmes, hackathons, and short-term experimentation initiatives. These are designed to introduce brief moments of learning and collaboration — short bursts of sense-making and connecting — often framed as ways of normalising experimental decision-making.

Yet, in practice, they frequently do the opposite. Because these initiatives are time-bound, performative and disconnected from approval, commissioning and resource-allocation processes, their outputs struggle to survive contact with existing governance routines. What is learned rarely reshapes decisions; instead, participants return to an architecture that rewards certainty, compliance, and delivery over adaptation. It is often theatre over substance.

Viewed in isolation, these initiatives can appear valuable. Participants report insight, energy, and motivation. But because they sit outside the moments where commitments are made, they offer no sustained pathway for learning to translate into public value.

This is not a failure of individuals or intent. It reflects a deeper structural issue. When learning is experienced as an exception rather than a condition of everyday decision-making, it is easily dismissed as “interesting but unrealistic.” Without repeated, consequential exposure to uncertainty — where learning genuinely alters direction — counter-intuitive ways of working struggle to stick.

Across each of these examples, the same pattern repeats.

Learning happens, but too late. Insight accumulates, but without leverage. Innovation is active, but powerless.

Seen through the waterfall architecture, this is not surprising. These mechanisms are attempting to introduce uncertainty, exploration, and adaptation into a system designed to eliminate them as early as possible. This is why mission-oriented approaches, design methods, and experimental practices so often collapse back into incrementalism: they are forced to operate after direction is set, resources committed, and alternatives foreclosed.

This is not a capability problem. It is an architectural one. Until the conditions exist for sense-making, connecting, and shaping to influence decisions when they matter most, innovation efforts will remain episodic and low-impact. Which leads to the next question: what would an alternative — complementary — decision-making architecture need to look like?

An alternative (mission-driven) decision-making architecture

Rather than replacing existing policymaking systems, this section sets out an overlaying decision-making architecture designed for moments of uncertainty. Drawing on Vinnova’s mission-design framework — and learning from the UK Government Digital Service’s agile delivery model for digital services — the model below translates these insights into a participatory decision-making architecture for moments of uncertainty. Its purpose is not to generate better analysis, but to change how direction, commitment, and resourcing decisions are formed by deliberately activating the dynamic capabilities discussed earlier: sense-making, connecting, and shaping.

Put simply, this architecture embeds learning throughout the policy design and delivery process, rather than treating it as something that arrives after key decisions have already been made.

This architecture rests on four principles.

- Conditional, not universal: It is activated only where uncertainty is high and stakes are systemic — not as a default mode of governance.

- Triggered by uncertainty, not default: It complements, rather than competes with, existing stewardship systems.

- Relational and procedural, not structural: it works through roles, practices and decision rights, not new hierarchies. This means a focus on making stakeholders active participants of the design process.

- Time-bound and reversible: Its purpose is to resolve uncertainty, not institutionalise exploration indefinitely. Results matter.

Critically, it also depends on what Dan Hill describes as “soft eyes”: the capacity to observe and work with the dark matter of bureaucracy — the informal relationships, tacit norms and interdependencies that sit between teams, directorates and policy domains. Without this, attempts to engage uncertainty are either blocked by premature certainty or absorbed back into business-as-usual routines before they can influence decisions.

This is not an abstract sensibility either. Variants of this capability have been articulated over the past decade through relational practices such as Relational Service Design, Human Learning Systems, Dark Matter Lab’s Governing Together, and the TEAL movement, which foreground trust, continuity, and institutional relationships as core operating conditions rather than delivery-side effects. The challenge is not their absence, but their marginal position relative to where decisions are actually made.

What follows sets out how this overlaying architecture works in practice: the stages it moves through, the capabilities it embeds, and how it interfaces with the state’s existing delivery and stewardship machinery.

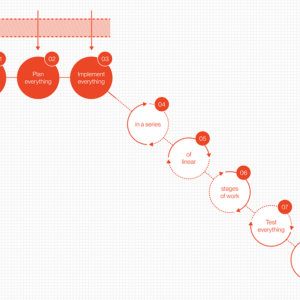

At a high level, the architecture is organised around four overlapping learning loops. These are not phases or stage gates. They are modes of work that structure how learning, judgement, and commitment evolve under uncertainty. What distinguishes this model from familiar innovation or design frameworks is not the loops themselves, but where decision authority and resource commitment sit within them.

The flow follows Vinnova’s mission-design framework, moving from Angles → Missions → Prototypes → Demonstrators, progressively reducing uncertainty while keeping direction open for as long as possible.

A. Angles: orienting the system

The Angles loop focuses on collectively developing an initial view of the system: identifying where uncertainty lies, what matters, and where intervention might be possible.

Rather than jumping to solutions, this loop brings a core group together to surface different ways of seeing the problem space. It deliberately draws together a trans-disciplinary team of policy, operational, user, technical, and political perspectives to build a shared orientation to the system as it is experienced, not just described.

The emphasis here is on sense-making and connecting. The output is not a strategy or recommendation, but a set of plausible directions — angles of intervention worth exploring further.

B. Missions: committing to direction

The Missions loop translates the most promising angles into statements of intent and design principles. These articulate what kind of change is being pursued and why, without prematurely specifying how it will be delivered. Design principles matter because they act as decision constraints under uncertainty — a function GDS has long used to align teams without over-specifying solutions.

At this point, connecting remains central — aligning actors around a shared purpose — while shaping begins to matter more. Missions create directionality by setting boundaries, clarifying intent, and establishing criteria for learning in the next stages.

Crucially, missions are treated as provisional commitments. They are strong enough to mobilise action, but flexible enough to adapt as learning accumulates. Their role is not to close down debate, but to focus it — similar to futurestate strategy or strategic foresight practices.

C. Prototypes: learning through tangible commitments

The Prototypes loop explores missions through a portfolio of concrete experiments — policy, service, regulatory, or organisational — designed to test assumptions and surface consequences.

Prototypes are decision-shaping commitments: deliberately designed to inform judgement about whether, how, and where to scale. Multiple prototypes ask different questions, reducing uncertainty through comparison rather than consensus. Vinnova’s Street Moves programme is a good example: place-based experiments used not as pilots, but as learning devices.

Here, connecting and shaping are tightly coupled. Prototypes act as boundary objects, aligning actors, mobilising resources and enabling learning through doing. The emphasis is not speed for its own sake, but efficiency: learning as much as possible for the least irreversible cost. Or, in Public Digital’s “The Radical How” terms: doing whatever it takes to speed up the loop of testing the things that matter the most and learning from the results.

D. Demonstrators: integrating learning at scale

The Demonstrators loop brings together insights from multiple prototypes into large-scale system demonstrations. These are not end states; they are decision-shaping devices. Their purpose is to determine whether uncertainty has been reduced enough to re-enter the state’s core delivery and stewardship architecture.

Here, sense-making resurfaces, alongside continued connecting and shaping, as priorities and resources are adjusted in response to what has been learned. Demonstrators help decision-makers see how interventions interact at scale before irreversible commitments are made. At this point, work can deliberately transition from exploratory modes into more stable delivery pathways — moving from adaptive learning to reliable execution.

Switching modes

At this point, I want to stress that this proposed second architecture is conditional, not universal. It is activated only when uncertainty is high — when outcomes cannot be reliably predicted, causal pathways are contested, and early lock-in would be costly or irreversible. It’s about introducing a dynamic learning process so that the state can return to its stable delivery architecture once uncertainty has been reduced.

When activated, several conditions matter:

- decision authority must sit close to the work

- learning must have formal routes into commitment and resourcing

- participation must include those affected, not only those accountable

- exit conditions must be explicit

The intent is not to weaken the state’s capacity for delivery, but to protect it by ensuring that stability is not achieved at the cost of learning, and that exploration does not become detached from power. In other words, this is not about replacing the machinery that keeps the lights on. It is about creating the conditions under which the state can decide differently when it needs to — and then return, deliberately, to what it already does well.

Preparing the ground: agile team models when working under uncertainty

Transformative change starts by preparing the ground: creating the conditions for a small, multidisciplinary team to work differently, with political cover, protected space, and the authority to bypass routine constraints long enough to prove what is possible. This was true of the early Government Digital Service in 2011, and it remains true of any attempt to change how the state decides under uncertainty.

Fundamentally, if we expect teams to sense, connect, and shape under uncertainty, we cannot treat them as interchangeable delivery units. Different phases of decision-making require different, malleable team purposes and archetypes that evolve as uncertainty reduces.

Kate Tarling’s work on service organisations is useful here. Rather than assuming static “agile teams,” she shows how teams shift over time: from exploratory, functional groupings with hand-offs, towards whole teams responsible for delivering and improving joined-up services. She stresses that hand-offs are not inherently problematic but they are often necessary early on — with problems arising when teams are locked into a structure that no longer matches the nature of the work and are forced into incompatible handovers.

It is therefore more helpful to think in terms of complementary team types, rather than a single ideal form. Drawing loosely on team typologies developed by Skelton and Pais (and Tarling), a mission-driven architecture typically relies on a portfolio of teams with distinct roles:

- Service teams are responsible for delivering and improving outcomes for users and operations.

- Depth teams, which explore complex issues, generate insight and reduce uncertainty on behalf of others.

- Common-capability teams, which build shared tools, platforms, and processes that make learning and delivery easier.

- Enabling teams, which unblock, coach, and support other teams to adopt new ways of working.

- Coordinating teams, which align activity across services or missions when interdependencies are high.

- Operational teams, which steward stable systems and deliver continuity over time.

Crucially, these teams do not all operate in the same way, nor at the same time. Early in the lifecycle of a mission — when uncertainty is highest — depth, enabling, and coordinating teams play a larger role in sense-making and connecting. As direction stabilises and uncertainty reduces, service and operational teams take on greater responsibility for shaping and delivery.

Seen this way, team models are not an implementation detail, but a core part of the decision-making architecture. Without the right mix of teams — and the ability for them to change as conditions change — even well-designed missions will struggle to move from exploration to impact.

Conclusion

The world is not a machine where, if you pull a policy lever, something will happen. Reconnecting policymaking with this reality means moving beyond top-down, disconnected approaches and towards a decision-making architecture that treats uncertainty as something to be worked with, not engineered away. One that embeds learning, judgement, and adaptation into how direction is set — without sacrificing the stability the state depends on. What’s required is strength without weight. The ability to do the hard things well, while remaining flexible enough to change when conditions demand it.

I want to be clear about what this piece is — and is not. It’s not a story of pessimism, nor a claim that the government lacks innovation or intent. Quite the opposite. There is a great deal of thoughtful, committed work happening across UK government and beyond (See: The state of British policymaking: How can UK government become more effective). This is an attempt to frame those efforts — through theory and lived experience — in a way that surfaces a deeper constraint: not ambition or capability, but the architectures through which decisions are made.

This article is not the answer either. The critique, and the model that follows it, could easily be read as two-dimensional: one person diagnosing a system and proposing a cleaner alternative. That reading misses the point. The issue is not a shortage of models for change. It’s that institutions — Whitehall included — often convince themselves they are uniquely resistant to new ways of doing, while continuing to route uncertainty through systems designed to suppress it.

This is as much a cultural challenge as a structural one. Work on systems change reminds us that transformation rarely follows linear cause-and-effect pathways. It emerges through overlapping activity, partial learning and shifting coalitions over time. For those of us working inside the government, that means holding multiple perspectives at once: staying curious, working across boundaries, and treating thinking itself as a form of action — something that shapes what becomes possible next.

Much of what I’ve drawn on here builds on existing ground: the early work of Government Digital Service, mission-oriented innovation frameworks, action-based approaches to social change, and emerging practices around Human Learning Systems and other relational practices. The open questions, for me, are less about invention than application. How do these principles actually reshape decision-making at scale? What role does digital play — not as infrastructure alone, but as an enabler of learning, coordination and judgement? Have we laid the horizontal foundations for a third era of digital governance, or are we still struggling to move beyond enterprise-era assumptions?

Those are questions for another time.

Next steps…

As with most of my writing on substack, this is thinking-as-writing rather than a finished argument. It’s an attempt to synthesise lived experience wrestle with the ideas and practices I’ve been immersed in over the past few years, to see whether they hold together. It’s written as self-provocations, loose ends, tensions and partial conclusions — that’s part of the point for me.

For now though, this thinking is feeding directly into my own work at HM Revenue & Customs where I’m currently leading a review of our internal Budget Policy Starter technology-impacting process by working with policymakers, solution architects, cost engineers and user-centred designers to better bridge stable and agile ways of working — and, in doing so, improve how policy decisions are shaped upstream so they serve citizens more effectively downstream.

This post is part of CIVICWORKS; a publication on (re)thinking civic bureaucracy, institutional reform, dynamic capabilities, policymaking and technology.

Beyond the waterfall state: why missions need a different decision-making architecture was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.