AI doesn’t just reflect human bias. It amplifies it through everyday use, quietly shaping judgement, trust, and decisions.

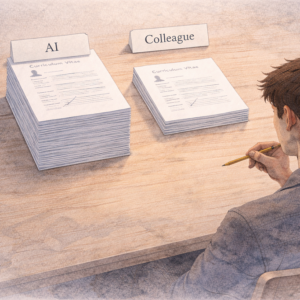

You’re halfway through a stack of job applications, AI assistant humming along beside you, flagging promising candidates like an eager intern. It disagrees with your gut feeling about one applicant. You pause. Reconsider. A few screens later, it disagrees again. You change your mind once more. By the end of the session, you’ve deferred to its judgment on nearly a third of the decisions where you initially felt confident.

Now swap the algorithm for a colleague. Same stack, same disagreements. How often do you actually budge? Much less often, as it turns out.

This isn’t hypothetical hand-wringing. Recent research involving 1,401 participants found that when people disagree with AI, they change their minds 32% of the time. With other humans, that figure drops to 11%. That’s almost three times more influence from a machine than from another person. Quite something, given we’ve spent millennia learning to be sceptical of each other.

We like to think of ourselves as rational decision-makers who simply use these tools as helpful aids. The evidence tells a different story. They do more than support our thinking; they reshape it. And far more powerfully than human opinions ever could.

This raises a question that should keep designers up at night: if users are this susceptible to algorithmic persuasion, what happens when the model itself is biased?

The answer isn’t just that users make biased choices. The effect compounds. Through repeated interactions, small errors snowball into meaningful distortions. And in most cases, users never notice it happening.

The amplification machine

To understand why AI influence packs such a punch, we need to look at what’s actually happening in the interaction itself. The problem isn’t one-sided. It’s a two-way street, with both the AI and the human feeding into a loop that amplifies bias at every turn.

On the AI side, these systems don’t simply reflect the patterns in their training data. They tend to exaggerate them. Machine learning models are optimised to detect and reinforce patterns, which means subtle skews in the data often become stronger in the output.

A hiring algorithm trained on historical data where 70% of successful hires were men doesn’t just reproduce that 70/30 split. It learns to weight male candidates more heavily, nudging the bias further along. The system is simply doing what it was built to do: find patterns and double down on them.

But that’s only half of the picture.

The human half of the equation

We don’t treat AI recommendations the same way we treat advice from another person. We tend to see automated systems as more objective, more analytical. Somehow immune to the messy biases that plague human thinking. This perception gets reinforced by how AI is marketed (“trained on the sum of human knowledge”) and by our long-standing trust in technology for high-stakes decisions in healthcare and finance.

Research from University College London and MIT shows just how potent this combination can be. Across a series of experiments, participants interpreted facial expressions, motion perception, and other people’s performance. In each case, they interacted with AI systems that had been deliberately programmed with biases similar to those found in many real-world models.

What happened next wasn’t just a momentary nudge. The distortion deepened. Through repeated interaction, small initial errors grew into significant skews. Participants who started with relatively minor biases ended up with significantly stronger ones. Largely because the AI amplified existing patterns while participants remained unusually receptive to its guidance.

Here’s where it gets uncomfortable: most participants had no idea how much the AI was shaping their judgement. When researchers told participants they were interacting with another person (while secretly using a machine), the effect weakened. Simply believing the source was human reduced how deeply the bias took hold.

Awareness mattered, but not in the way we might expect. Knowing that the advice came from an algorithm made people more susceptible, not less. We expect AI to be right, so we lower our guard. It’s the automation equivalent of assuming the smoke alarm would have gone off if there were a real fire.

Even more troubling: this effect doesn’t vanish when the AI does. A 2023 study had participants assess medical images (specifically, deciding whether skin spots were benign or potentially cancerous) using a deliberately biased algorithm.

When the system was removed, the bias stuck around. People continued making the same skewed calls on their own, having unconsciously absorbed its patterns into their decision-making. The higher someone’s self-reported trust in automation, the more their independent conclusions mimicked the machine’s errors.

The path of least resistance

Our vulnerability to AI isn’t just about trust in technology. It’s rooted in something rather unflattering about how our brains handle effort.

Psychologists call this the cognitive miser effect. Thinking is expensive (metabolically, emotionally, and in terms of time) so when we’re handed an opportunity to reduce mental effort, we tend to grab it. These systems offer a particularly seductive shortcut: offloading complex judgement to something that appears faster, smarter, and more thorough than we could manage ourselves.

This helps explain why automation bias shows up so consistently. Studies show that when people work with automated decision-support systems, they dial back their own monitoring and verification. The presence of AI doesn’t just influence decisions; it quietly changes how much effort we put into thinking at all.

We see the recommendation, and it feels complete. The work appears to be done. On to the next thing.

But this isn’t purely about conserving effort. We also tend to believe that these tools have analytical abilities that surpass our own. In some domains, that belief is justified. They can crunch enormous datasets, spot patterns at scale, and perform calculations far beyond human capability.

The problem is that we extend this assumption into contexts where it doesn’t hold.

The fact that an algorithm can analyse thousands of medical images doesn’t mean its assessment about an individual patient is infallible. Just because a system can process every CV in a database doesn’t mean it grasps what makes a good hire in a specific team. The leap from “impressive at scale” to “trustworthy in specifics” is one we make far too readily.

When trust spirals

The evidence on automation bias shows that inexperience and low confidence amplify this effect. When people feel uncertain about their own abilities, or when they’re working under time pressure, they’re more likely to defer to the machine.

This creates a rather unhelpful loop. The more we rely on AI, the less we exercise our own judgement. The less confident we become, the more we rely on it. Keep that cycle spinning long enough, and your decision-making instincts start to gather dust.

Branding matters too. Studies have found that when users are told they’re working with an “expert system” rather than a basic algorithm, they’re more likely to follow its recommendations — even when those recommendations are wrong. How we label AI directly shapes how much trust users place in it.

There’s also what researchers call “learned carelessness”. When these systems perform well over time, users gradually reduce their vigilance. High reliability leads to complacency. If the system has been right 95% of the time, we stop checking as carefully. And when it stumbles on that remaining 5%, we’re rarely prepared.

More than the sum of its parts

For a long time, AI bias and human bias have been treated as separate problems with separate fixes. We try to clean up training data and fine-tune models. We train users to recognise their own blind spots and think more critically. Both approaches matter, but they miss something essential. What emerges from human–AI interaction isn’t simply one plus the other. It’s compound bias. Something new that arises specifically from the interplay between the two.

Think of it less like an equation and more like a chemical reaction. When certain elements combine, they don’t just sit alongside one another. They interact, producing something neither had before they met.

A recent paper makes exactly this argument. Bias doesn’t live solely in the model or in the user. It emerges dynamically through feedback loops that evolve over time, each party making the other a little worse with every exchange.

Medical AI studies illustrate this clearly. In a 2025 study, researchers examined what happens when class imbalance in AI systems meets human base rate neglect.

Class imbalance is a technical bias where rare conditions are underrepresented in training data. Base rate neglect is a human cognitive bias where we struggle to reason accurately about low-probability events. Individually, each causes predictable problems.

Together, they produce something worse.

Class imbalance throws off people’s ability to gauge how much they should trust the AI. Base rate neglect makes users more vulnerable to skewed outputs. Each bias reinforces the other, creating feedback loops that lead to poorer outcomes than either would cause alone.

The errors don’t add up. They multiply.

Fixing the wrong problem

This is why traditional debiasing strategies often fall short. You can scrub training data and tune algorithms all you like. But if the interaction pattern itself amplifies bias, you haven’t solved the problem. You’ve just trimmed one input to a system that compounds errors regardless.

The same goes for human-focused interventions. Teaching users about cognitive bias is valuable, but if the interface encourages offloading and discourages verification, that knowledge stays theoretical. Filed under “good to know” and rarely retrieved.

The question shifts. It’s not “is the AI biased?” Or even “are the users biased?” Instead, it goes: “does this interaction create bias amplification over time?”

That’s a fundamentally different design challenge.

Mirror, mirror in the interface

AI doesn’t just mirror our biases. It amplifies them. Quietly, incrementally, and often invisibly. The problem isn’t confined to training data or human psychology alone. It lives in the space between humans and machines, shaped by how each influences the other over repeated interaction.

For designers, this reframes what we’re solving for. We can’t simply debias algorithms and dust off our hands. We can’t rely solely on user education. The bias emerges from the interaction itself. From patterns of trust, deference, and cognitive offloading that compound with every exchange.

Which brings us to the real question.

If this amplification happens through everyday interactions with AI, where is it already showing up most strongly in the products we use today?

The research points to a particular type of interface. One that feels natural, helpful, and conversational. In these interactions, users don’t just follow biased recommendations. They begin to internalise them, carrying those biases forward even after the interaction ends.

And that’s precisely what makes it so hard to see.

Thanks for reading! 📖

If you liked this post, follow me on Medium for more.

References & Credits

Glickman, M., & Sharot, T. (2024). How human–AI feedback loops alter human perceptual, emotional and social judgements. Nature Human Behaviour. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-024-02077-2

Sánchez-Amaro, A., & Matute, H. (2023). Humans inherit artificial intelligence biases. Scientific Reports, 13, 15737. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-42384-8

Goddard, K., Roudsari, A., & Wyatt, J. C. (2012). Automation bias: a systematic review of frequency, effect mediators, and mitigators. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 19(1), 121–127. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3240751/

von Felten, N. (2025). Beyond Isolation: Towards an Interactionist Perspective on Human Cognitive Bias and AI Bias. CHI 2025. https://arxiv.org/html/2504.18759v1

Biased Minds Meet Biased AI: How Class Imbalance Shapes Appropriate Reliance and Interacts with Human Base Rate Neglect. (2025). https://arxiv.org/html/2511.14591v2

Automation bias. (2025). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Automation_bias

Bad (model) behaviour by design was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.