For AI to succeed, we’ll need to devise new interface patterns that support its capabilities rather than copy those patterns of the technology it seeks to replace.

As the joke goes, the best place to hide a body is on the 2nd page of google results. No one clicks to the next page.

The Google search paradigm

Google built the paradigm for all of search around an extremely simple user experience: user asks a simple question (search query) and Google serves up relevant results in the first few entries. A design principle of Google early on was that they would not ask anything more from the user. This was revolutionary–I remember earlier search engines such as Lycos, Alta Vista, Yahoo employing various filtering tools as part of the experience. Google’s genius was doing the opposite: they focused all of the improvements on delivering better results while explicitly never asking more of the user.

Text entry field, submit button. User types a question. Google provides an answer. This interaction became the most ubiquitous digital experience on the internet. Everyone has used it thousands of times. The pattern is deeply ingrained in our minds. Any deviation feels wrong.

The AI interface mismatch

And now AI comes along, gives us the exact same UI, and expects us to behave differently. In that familiar text field, a user must write a prompt that has several parts to provide context, persona, desired output format, and more. Then they’re expected to have a back–and–forth conversation with the interface to refine the output and provide additional context.

You see the problem?

The interface promises the simplicity of search but demands the complexity of programming. We’ve trained users for 25 years to expect immediate, comprehensive results from brief queries, then asked them to master an entirely different set of skills using an identical user interface.

Early adopters and tech enthusiasts will endure this learning curve–the pain of mastering something new is worthwhile when they can envision the potential. But that’s not most people.

I’ve been using AI for over a year. Initially, it was frustrating. I believed the hype but couldn’t realize the practical (promised?) value. Only through persistent experimentation did I learn effective prompting techniques and identify valuable–to–me use cases. The technology evolved from awkward and forced to genuinely additive. But the key point: it required significant effort on my part to get there.

From one interface, infinite outcomes

Perhaps the biggest user challenge is that people can’t grasp the breadth of what AI can accomplish. Consider these wildly different use cases:

- Blog post: Generate content based on a simple theme or a couple lines of an original idea.

- Mockup: Generate a clickable prototype of a mobile app based on simple instructions.

- Training program: Develop a schedule with routine steps to follow so that I can develop a new habit.

- Presentation: Create an outline for a slide deck presentation.

- Debate: Help someone think through a complex idea and identify gaps and opportunities.

- Visual ID: Generate a whole brand identity for a new product.

Each started from the same UI: a blank text field.

The possibilities feel endless, which paradoxically makes AI feel overwhelming and impractical. Without effective signposts, users can’t keep track of all the many things AI might accomplish for them. The cognitive load of remembering and formulating requests for dozens of potential use cases creates a massive adoption barrier.

When it requires more than a conversation

For quick questions and answers, a chat box is a fine interface to use. After all, that’s really just the search experience: ask Google a question and get an answer. AI is striving for richer experiences. Linear dialogues — back-and-forth question and answer with AI will not bring that about.

Elizabeth Laraki, Design Partner at Electrical Capital, recently wrote about this on her Substack. In “UI is the limiting factor for AI” she discusses the challenge of using ChatGPT to develop an itinerary for a day in Madrid with her 7-year-old son:

“ChatGPT did offer some good ideas and the recommendations were all reasonable. It was the UI that was the problem: The UI didn’t support a conversation that built on itself and didn’t provide any reasonable way to co-create an itinerary.”

She notes that human conversation is non-linear — one dives into a sub-topic, jumps back out, changes subjects, tables something for later, comes back. Being able to truly collaborate on an output — in Elizabeth’s case the walking itinerary — where the user can make changes both through conversation (text field entry) and through editing tools, should be the goal. AI doesn’t support that sort of interaction at this time.

Building a new interface paradigm

What should replace the simple search box? This will likely take time to emerge as AI companies experiment with new input controls. While the complete solution remains unclear, several key principles emerge:

(I should note that many of these ideas listed are being worked on by AI companies today and have been released in some fashion)

Contextual awareness. AI doesn’t need to go in every direction when I first engage it. It should understand who I am, where I am, and what I’m likely trying to accomplish, then adapt to support the most probable use cases. Memory of past interactions was a step-change improvement when LLMs began incorporating conversation history. Google released this to Gemini earlier this year. OpenAI added it to ChatGPT last April. More of this type of recall will help.

Adaptive UI. Because possible outputs vary greatly, the inputs will need to be equally different. Sometimes text is optimal. Other times voice, images, or autonomous execution make sense. The UI should morph to match the task rather than forcing everything through a single input method. NN/g released an article last year on this, by Kate Moran and Sarah Gibbons, “Generative UI and Outcome-Oriented Design” where they explore the idea of apps fundamentally changing based on user and intended task.

Discrete task-focused components. Rather than cramming infinite possibilities into one box, we need specialized agents that excel at specific functions. These components should understand each other’s function and connect intelligently. When users have a particular need, the appropriate agents should collaborate to deliver an optimal result.

Real-time feedback and guidance. Current AI interfaces leave users guessing whether their approach will work. The system should provide insight into what’s working in a prompt and suggest improvements, rather than leaving the user to experiment blindly.

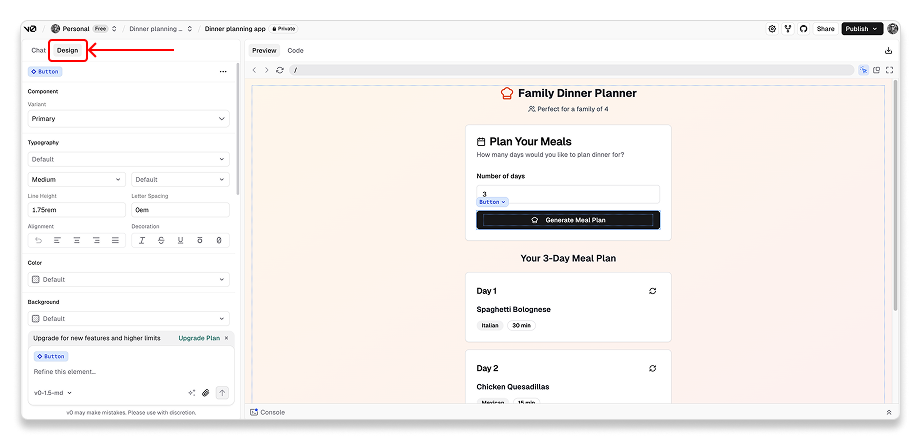

Refinement tools. One of the biggest frustrations with AI is a “close-but-not-right” output. It is really hard to make small but important adjustments to an AI output. This is particularly true with image creation or generated prototypes. More precise tooling around editing will be immensely helpful and avoid needlessly starting over. Some companies are starting to offer such editing options. Midjourney offers users some controls. Vercel just added a design mode to v0.

The path forward

The companies that solve this UI challenge will be doing more than just improving the user experience–they’ll be unlocking AI’s mainstream potential. It isn’t about incremental improvement to chat interfaces. It’s about fundamentally reimagining how humans and AI collaborate.

Google’s breakthrough was radical simplification–removing friction that competitors had normalized. AI needs its own paradigm shift. We need interfaces that wrangle the inherent complexity of AI into something that feels effortless and intuitive.

AI will transform how we work, create, and solve problems. However, this transformation will remain beyond most people until we redefine the interface in a way that makes sense to humans.

Additional reading

The intersection fo AI and product design generates a lot of interest. Here are some additional posts on this topic that I’ve found particularly interesting or useful:

- “Rethinking interfaces for AI era. Why buttons and text boxes won’t cut it anymore,” by Prashant Singh

- “UI is the limiting factor for AI,” by Elizabeth Laraki

- “Generative UI and outcome-oriented design,” by Kate Moran and Sarah Gibbons

- “Conversational interfaces: the good, the ugly & the billion-dollar opportunity,” by Julie Zhuo

AI needs a new UI was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.