What were the discussions and suggestions proposed by the international community in 2024?

Many designers and developers care about accessibility in digital products, as pointed out by Forrester in the Config 2024 analysis. The desire is there, but it’s not always possible to implement accessibility systematically and at scale in daily practice. Why? We lack time and study, and there’s an overwhelming amount of content to consume.

In 2024, more than 40 resources on Accessibility in Design Systems were published in English, totaling over 12 hours of videos and podcasts. This volume is no coincidence: creating accessible and scalable interfaces is a challenge that goes beyond the conventional digital accessibility debate. Deep questions are being raised, such as: What does scalable accessibility in digital products truly mean? What is Shift Left, and how can an accessible DS evolve? Is it possible to have control within a team and document all accessibility tests in a DS?

Who can absorb so much content without getting lost along the way? The truth is that, by trying to keep up with so much information, we end up consuming only a fraction and fail to get a panoramic view of the key debates. With that in mind, I decided to create this retrospective, analyzing all these resources to identify the main insights and discussions that shaped the past year.

The idea is simple: to offer an overview that helps us understand what’s currently on the agenda when it comes to accessibility in Design Systems. What progress has been made? Which questions remain unanswered? Where can we dive deeper into specific topics?

This text is an invitation to that conversation — less about what we already know and more about what we are still discovering as a community. Feel free to contact me via my LinkedIn for any type of feedback.

Sections

- Methodology

- Why Design Systems for Accessibility?

- What Is Accessibility in Design Systems?

- How to Evolve an Accessible Design System?

- How to Test an Accessible Design System?

- How to Organize Accessibility Tests?

- How to Document Tests?

1. Methodology

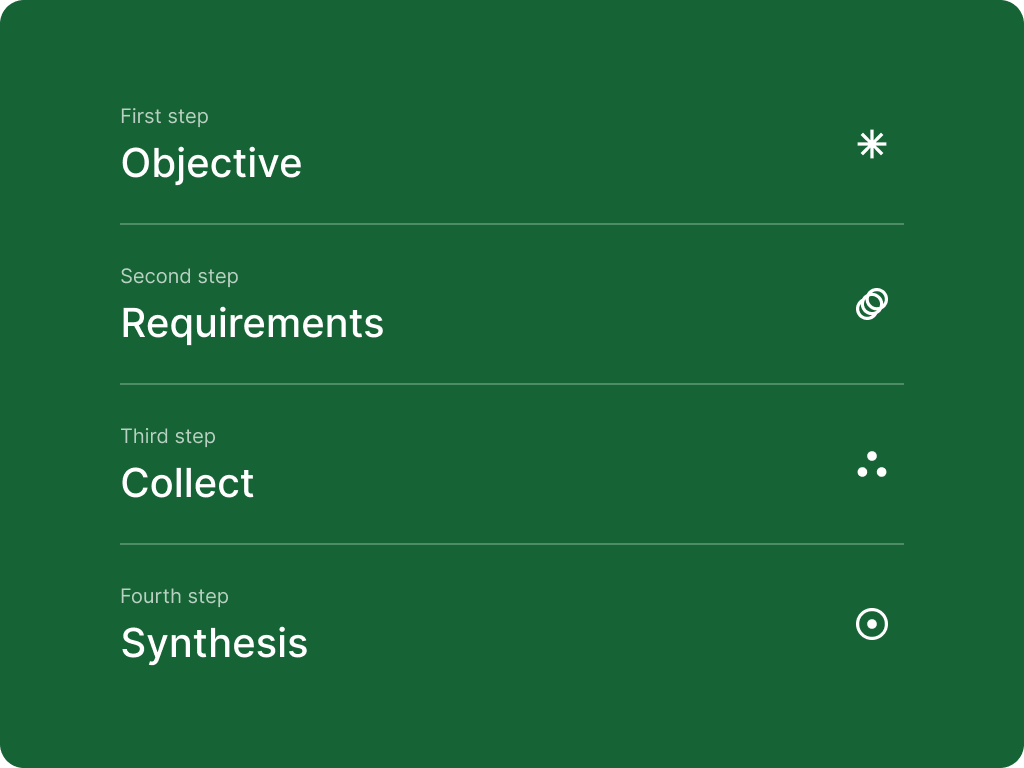

Before diving into the discussions, let’s take a look at the methodology behind this study to understand what was said in the international community about Accessibility and Design Systems in 2024.

If you’d rather skip this part, feel free to jump straight to the next section to see the research results. But if you’re interested in how the data was gathered, take your time to go through this step-by-step breakdown.

All data collection was conducted through a systematic review of educational materials published on two intersecting topics: “Design Systems” and “Accessibility”.

Before starting the material collection, every systematic review must establish an objective. The goal of this retrospective was to understand the discussions surrounding the challenges of building accessible digital products, particularly through Design Systems. This is a specific topic within the UX Design and development field that generates a large volume of content every year, allowing for retrospectives to identify key debates that took place over an extended period, such as a year.

Any retrospective review needs to be transparent about how its data collection and analysis were conducted to avoid privileging certain documents over others. Below are the basic inclusion and exclusion criteria for the materials collected in this study:

- The content had to be published in 2024.

- The material needed to be in English, as the goal was to provide an overview of the international scenario as comprehensively as possible.

- The material had to have an educational purpose to capture the challenges shared with the community. Educational materials were understood as: articles (informal and non-academic), podcasts, or videos created/published by industry experts addressing the topic. Therefore, this article does not review other types of materials, such as accessibility documentation within Design Systems published in 2024. If you’re interested in this type of documentation, check out the example of the Carbon Design System. Although essential as reference points, such documentation is often very specific to an organization’s guidelines and lacks the broader professional debate found in educational publications.

- Materials had to be free of access restrictions. Due to copyright constraints, paid educational materials — such as course content or subscription-only articles — were not analyzed or cited. Furthermore, it’s worth noting that such paid content was not found in abundance during the searches conducted.

Based on these criteria, the search terms used were “Design System” and “Accessibility” in major search tools similar to Google. An exploratory analysis was also conducted with additional terms, such as “Design System” and “Blindness” or “Design System” and “Neurodivergency”. However, no significant number of relevant materials from 2024 was found using these terms. As a result, it was deemed unnecessary to search for more specific terms beyond Accessibility to conduct this retrospective discussion.

Finally, for full transparency, you can find all the materials collected at the end of the article in the references section. The most notable ones are cited with links throughout the text. Some materials, while not explicitly mentioned in the article, were analyzed and contributed to the broader arguments found across multiple resources.

Is it clear how this review was carefully conducted to ensure we didn’t miss anything on this topic? If so, let’s move on to the synthesis of the debate.

2. Why Design Systems for Accessibility?

Before diving into the details, it’s worth taking a moment to reflect: why are Design Systems increasingly seen as an effective path to improving digital product accessibility? The answer begins with three words: speed, consistency, and technical accuracy.

In a scenario where digital interfaces are becoming increasingly complex, a well-structured Design System is like a compass that keeps accessibility on the right track. Tyler Hawkins, software engineer at Webflow, summarizes this idea well: each component needs to meet a series of technical criteria to be accessible to different audiences. Without a solid and centralized foundation, this can turn into chaos, especially in companies that manage multiple products simultaneously.

This scalability is also discussed for the creation of more customizable platforms. Several materials argue that platforms built with Design Tokens help create specific themes for certain communities with some type of disability. One example of this can be found in Georgi Georgiev’s (designer at PROS in Bulgaria) text about the creation of high contrast modes (High Contrast Modes) from Design Systems — a dark theme that differs from the common Dark Mode by being intended for users with some kind of visual impairment or photosensitivity (sensitivity to light).

As expected due to the debates of the past decades, this scalability is widely defended with the application of the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) as an international guideline. This is because the WCAG provides research-based requirements that must be met by objective and measurable criteria to assess the success or failure in creating an accessible digital product. Many professionals highlighted the historical role of the WCAG in creating a common language capable of internationally standardizing the legal accessibility requirements for digital products — a reflection of the transition from digital accessibility being a recommendation to an obligation in many countries in the last decade. In 2024, several governmental DSs advanced in their compliance processes with the WCAG guidelines, driven by national legal requirements — such as the United States Web Design System (USWDS) in the United States and the NL Design System in the Dutch government.

However, a challenge in achieving this standardization is discussed by Amy Cole (Digital Accessibility Lead at USWDS): many designers and developers fear WCAG because it is a very technical language. This fear stands out as a major obstacle, fueling a widespread call for more accessible educational materials and dedicated accessibility study groups to foster awareness within organizations. It is not trivial that, along with the WCAG, supplementary tools are always mentioned to assist in this challenge, such as the IBM Equal Access Toolkit, the Microsoft’s Inclusive Design Toolkit, The A11y Project, and Deque Systems.

Therefore, having a DS also helps in this process of conformation, as the team can create cascading processes that start with specialists and reach professionals who are not specialized in accessibility more smoothly.

But, all of this depends on what is understood by accessibility and technical compliance…

3. What Is Accessibility in Design Systems?

Daniel Henderson-Ede (Accessibility Specialist at Pinterest) brings an important reflection: accessibility goes beyond ensuring that a component is technically compliant with the WCAG. He explains that, although accessible components are key pieces to start an accessible interface properly, the complete puzzle only forms when the experience as a whole is considered. A classic example of this is the focus order in an interface: if the components are not organized logically, keyboard navigation becomes frustrating, even if each individual piece meets the standards.

For this reason, one of the biggest debates that permeates the construction of an accessible DS is about the understanding of what accessibility really is. Cintia Romero (designer at Pinterest) describes that this accessibility tied to the WCAG guidelines is just an initial technical compliance. This does not imply that compliance is not essential, but she points out something important that many professionals brought up in 2024: mere adherence to standards does not necessarily mean meeting the real needs of these user groups.

That’s why she highlights Inclusive Design, alongside technical compliance, as a key approach within Design Systems — ensuring a more human-centered and holistic perspective in interface testing. Here, accessibility is integrated into User-Centered Design methodologies, ensuring that multiple usage scenarios for diverse users are thoughtfully considered. Complementing this view, Hidde de Vries (Accessibility Specialist at NLDS in the Netherlands) proposes that, instead of treating disability as a personal limitation to be mitigated — what would be a medical model of thinking —, we should adopt the social model of accessibility, which makes us consider the social context around a person with some condition.

To understand how to approach this social responsibility, Greg Weinstein (designer at CVS Health) helps us by mentioning that an Inclusive Design System is also connected to intersectionality— a concept borrowed from authors such as Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989). This concept is used to show that different characteristics (such as race, class, sexuality — or even different types of coexisting disabilities) overlap and interact, creating particular experiences. Thus, it is not just the screen reader (or any other technology) that needs to work well in this more holistic perspective! It may be necessary to think about the elderly person with low vision who also needs simple interfaces due to their age. Or, as another example, it may be necessary to consider the low-income user with hearing loss who faces financial difficulties in purchasing modern devices.

In the end, this conversation shows that a Design System goes beyond ensuring perfect compliance in isolated components. It provides the foundation to achieve this compliance systematically, but its true value lies in allowing it to deepen and expand over time. It is about testing solutions in real contexts, with real people. It is a continuous process of evolution, where technique inevitably meets humanity.

4. How Do You Evolve an Accessible Design System?

You’ve probably heard the saying that accessibility only truly works when it’s considered from the very beginning of the process — an approach known as Shift Left.

Simon Mateljan (Design Manager at Atlassian) makes a simple and effective analogy: creating accessibility in a Design System is like adding eggs to a cake recipe. If you forget that ingredient at the beginning, the final result will never turn out as expected. This logic makes sense, as ensuring accessibility from the start helps permeate it through all stages of development. But the debates of 2024 showed that this journey is far from linear! There is no perfect starting point — the process is continuous and full of adjustments.

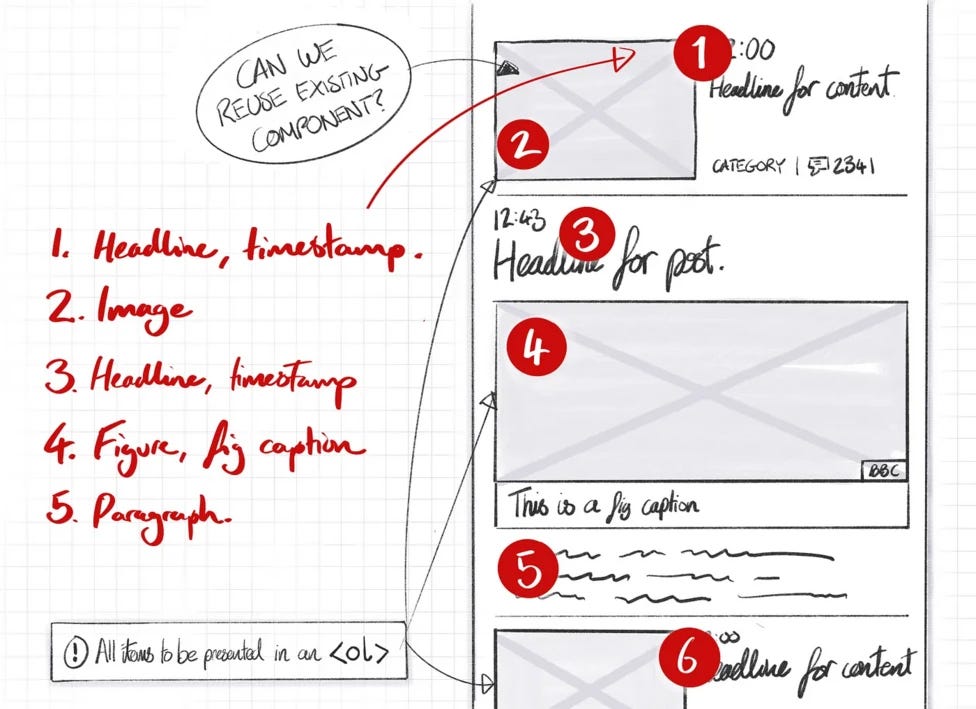

Sophie Beaumont (Design System Team Lead at BBC) shows how Shift Left can happen in the evaluation of component reuse across different contexts. She describes a case where the BBC team tried to reuse an existing component to create a content timeline. Although the Design System already had a visually similar component to what the team had designed, it did not meet accessibility requirements in the new context. After internal discussions and technical evaluations, the team concluded that forcing the use of the old component would harm the experience for users with disabilities.

This decision led BBC to strengthen a work process that prioritizes functionality over appearance when evaluating component usage. This work process is crucial to prevent a Design System from creating rigidity, making accessibility harder rather than improving it. In addition to this, Feli Bernutz (iOS Developer at Spotify) presents “The Game Plan” (timestamp: 16:55) — a work methodology that evaluates when to use a ready-made solution and when to think outside the box to create something more customizable.

Furthermore, unforeseen issues can create unexpected needs, going beyond the simple creation of new components. One example of this is Pinterest, which allows users to add alternative texts (Alt Text) when creating Pins. This open and collaborative content model presents unique challenges for accessibility, as many users either do not create descriptions or produce poor-quality Alt Text.

Due to the platform’s design, Pinterest cannot simply impose rigid limitations to ensure Alt Text consistency. Instead, the team invests in educating users by offering clear instructions through interface components on how to create useful and contextualized descriptions. This process shows that, in certain cases, it is necessary to adapt the technical guidelines of the WCAG to the specificities of each digital service.

Therefore, many statements from 2024 emphasized that mistakes are part of the Design System creation process, especially in contexts where needs vary as the product matures. Even in the Encore Design System at Spotify (a product of huge scale), the approach is iterative: rather than pursuing a perfect solution from the start, the team seeks progressive improvements at each step, climbing one step at a time. At the UXCon in Vienna, Join Wendy explains that the creation of inaccessible DSs at the beginning does not mean the end of the process — it may, in fact, be the beginning of understanding particular challenges.

So, how to balance all of this? On one hand, Shift Left suggests that accessibility should be a concern from the very beginning. On the other hand, the continuous discovery process reveals specific needs that require adjustments and adaptations. In the end, building an accessible Design System is less about achieving a perfect state and more about staying open to learn, test, and constantly improve.

5. How to Test an Accessible Design System?

Because of everything that has been said so far, it is clear that an accessible Design System is not born ready — it is a continuous construction, refined over time and, mainly, through many tests. But, given the complexity of creating truly inclusive interfaces, the question arises: what kind of testing needs to be done to achieve this goal?

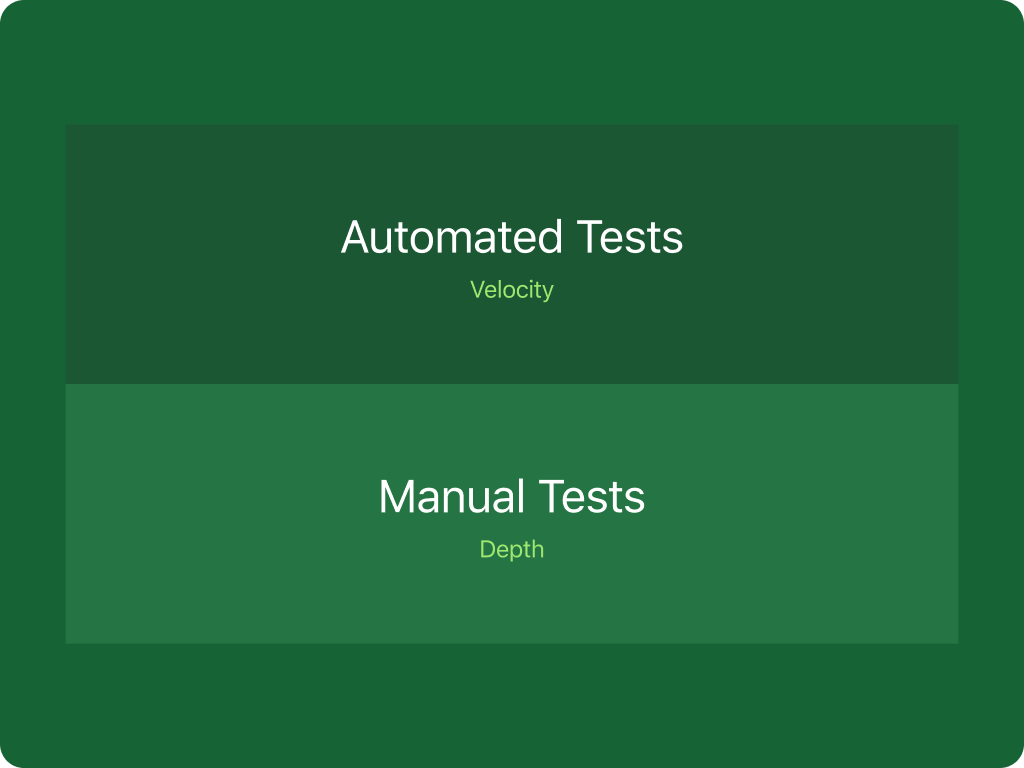

In 2024, the debate about accessibility in digital products highlights the importance of automated testing (and the possible use of AI), especially in Design Systems that are already implemented at the code level. Tools like Axe, Lighthouse, and other automated solutions are gaining ground as major allies in this process. And, in fact, it would be naive to underestimate their importance: they offer speed in identifying common errors and helping teams achieve compliance standards.

Moreover, in a Figma live session, Luis Ouriach (Designer Advocate at Figma) and Daniel Henderson-Ede (Accessibility Specialist at Pinterest) emphasized that native apps, such as those developed for iOS and Android, present unique challenges. Unlike the web, where standards like HTML and ARIA provide a solid foundation, native platforms have specific toolkits, such as UIKit on iOS and Jetpack Compose on Android. This fragmentation requires teams to adapt their practices to ensure accessibility across different environments.

Daniel also pointed out that validation tools for native apps are less integrated into the development flow. While solutions like Axe and Lighthouse work directly on the web, mobile apps rely on tools like Xcode Accessibility Inspector or Accessibility Scanner, which, although useful, have limitations and do not easily connect to the continuous development process. To address these challenges, the recommendation is to incorporate platform-specific tests and train teams on the nuances of each technology — requiring the development of tailored testing and documentation processes within a Design System.

However, there are clear limits to this approach, as reminded by the WebFlow article, which showed that automated tests can only identify about 30% of accessibility issues. This limitation brings us to a crucial point that was mentioned by the vast majority of materials from 2024: automation does not replace the human eye. Manual testing and, especially, interaction with real users are indispensable to understanding the practical experience — something that automated reports cannot capture.

That being said, it is evident why so many materials are dedicated to explaining how to create accessibility tests, also highlighting the challenges of developing proper documentation to accompany and control this continuous process of evolution.

6. How to Organize Accessibility Tests?

Many materials suggest starting with the adoption or creation of checklists. Depending on the content in question, checklists can be filled out after manual tests or automated tests. Here, the debate is less about the testing technique and more about how to systematize the organization of these tests within a team.

Amy Cole, from the US Web Design System (USWDS), sees checklists as bridges between what is in the manuals (such as WCAG) and what actually happens when a user navigates a product. These guides serve as scripts that allow even less specialized teams to engage in practical testing with real users. Therefore, the checklist is discussed here not only as a tool for systematizing tests but also as a process of inclusion for those who feel disconnected from the WCAG criteria due to its technical language. This is why the USWDS team suggests questions like:

- “Can the button be activated with the Enter key or the spacebar?”

- “Is the focus clearly visible in all button states?”

The suggestion is to create these questions with various teams, including specialists and allowing for a collaborative and multidisciplinary view. Here, the USWDS material highlights the importance of having control through documentation to understand which WCAG criteria have been considered with each of the suggested questions.

Wendy Fox, at UXCon Vienna, complements this view by discussing the importance of conducting audits to go beyond generic checklists that would apply to any scenario. A link in a dynamic carousel, for example, cannot be evaluated the same way as a static link in a text. For this reason, she advocates for personalized checklists that consider the uniqueness of each component: for a button, this might mean checking if there are visible focus states; for a modal, ensuring that keyboard navigation flows naturally. These are criteria that not only ensure compliance but also make the experience more fluid and respectful for those who rely on assistive technologies.

Amy Hupe and Geri Reid, from the UK Government Digital Service (GDS), emphasize that these checklists need to consider the tools users employ. Here, different tests are suggested, such as: 1) keyboard access; 2) zoom/magnification; 3) screen readers like NVDA and JAWS; 4) eye trackers. These are suggested by the designers as a guide to understanding accessibility beyond a generic and general concept, potentially including technology type by device. Since there are many different disabilities and contexts to consider, tests can indicate which assistive technologies have more support in the Design System and which still need to evolve to create a better experience.

Additionally, it’s important to note that most materials stress the importance of speaking with real users in qualitative research. Still, I emphasize that this remains the least discussed topic in all the 2024 materials, as much of the focus is still on the individual pieces of the Design System rather than on testing the assembled interface already presented to end users.

7. How to Document Tests?

One of the biggest challenges is the documentation of accessibility tests that allow the evolution of an accessible Design System. It’s not trivial that some of the 2024 materials go in-depth into the challenges of constructing and maintaining these tests over time.

You can work with both accessibility documentation in design (using Figma as a recording space) and documentation of general tests carried out on already developed interfaces, which typically takes place in Excel spreadsheets, GitHub or on Design System websites. There’s no consensus on which of these documents is the most relevant, but different professionals defend the proposals, considering their different purposes.

In Pinterest’s Gestalt, Cintia Romero exposed that there’s an integration of checklists directly into Figma as a way to bring designers closer to accessibility practice. According to a case study by Deque, 67% of accessibility issues occur due to errors in design prototypes! This data debunks the idea that tests and accessibility documentation should only occur at the development level. For this reason, some platforms have this documentation within Figma itself so that the handoff of products is in compliance with accessibility standards before moving on to code-level tests.

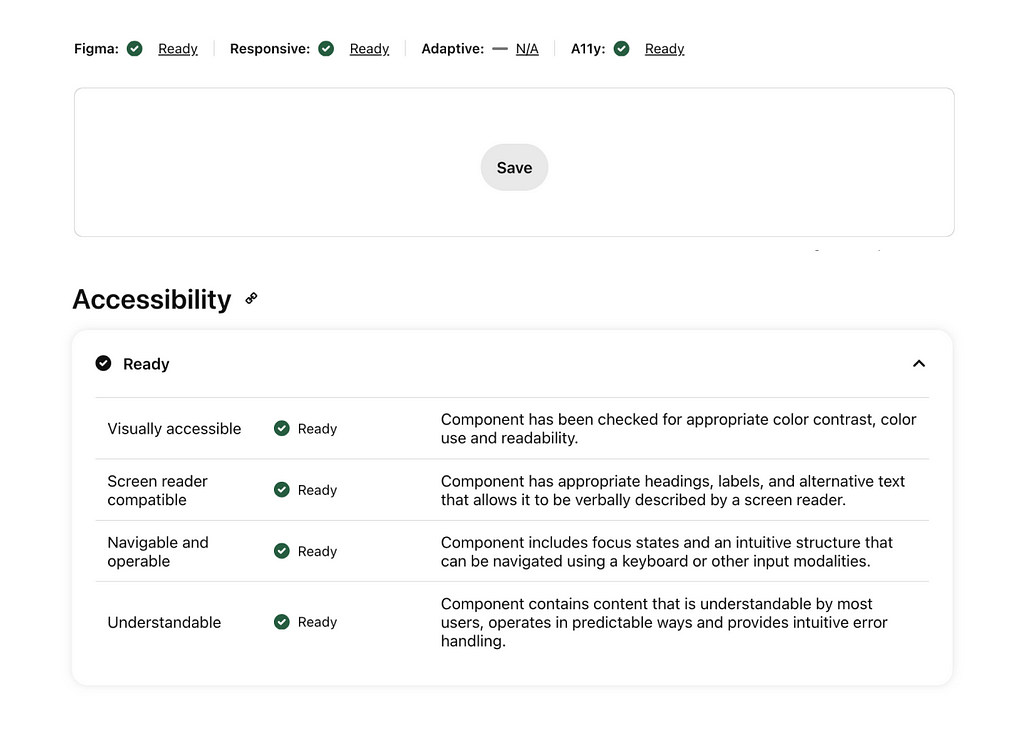

This documentation is often later transferred to the component page on the Design System website, as we can see next in the case of Gestalt.

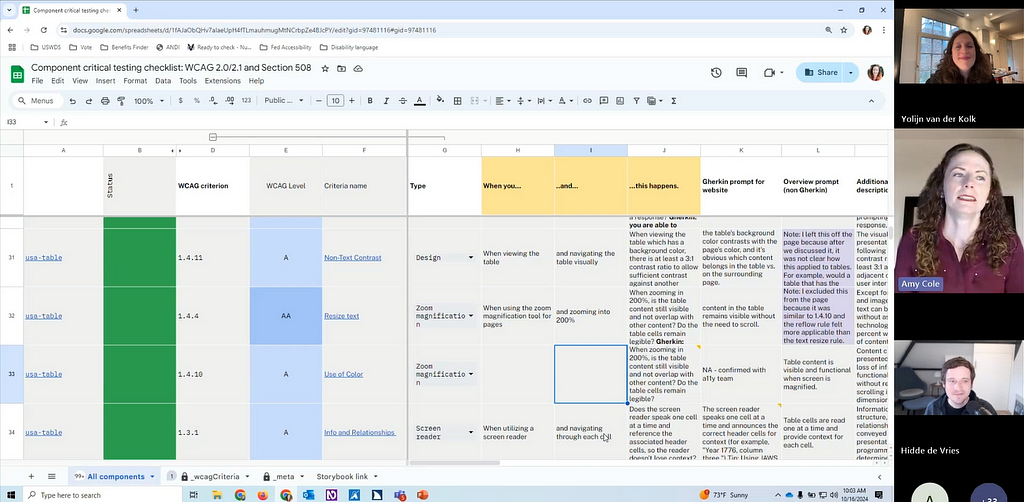

This is a more concise documentation proposal. Other projects opt for much more robust and detailed documentation, containing success criteria and the type of test conducted (including which assistive technology is involved). This is the challenge faced by the USWDS team, which organizes test data (manual and automated) for all the components of their Design System. To do this, the team uses a spreadsheet that contains:

- Component Name: The name of the component being audited.

- WCAG Success Criterion: The specific criterion being tested, such as “1.4.4 Resize Text” or “2.1.1 Keyboard Accessibility.”

- Compliance Level: The WCAG compliance level (A, AA, or AAA).

- Test Type: Whether the test is related to keyboard, zoom, screen readers, design, or another aspect.

- Test Status: Whether the test passed, failed, or passed with exceptions.

- Additional Description: Details on how the test was conducted and what the developer should observe. There are three columns titled “When you,” “And,” and “This Happens” that allow you to explain a success or failure case.

- Automated Test Prompt (if applicable): Exposure of the test prompt for control over how the testing was conducted.

- Audit Date: The date the test was conducted and revalidated to control results and possible WCAG updates.

- Other columns for Notes and Common Failures: Observations on common issues found during testing, including contributions reported via the project’s GitHub.

In both cases, there are very important challenges highlighted in these materials. In the case of USWDS, Amy Cole explains that component re-audits are regularly carried out to understand if new scenarios need to be considered — such as, for example, changes in browsers for web components. Also, there may be changes in assistive technology used by a group of people, requiring new tests without losing the old documentation.

Another point of attention is tests that go beyond the components themselves, as Fable comments in an article on different levels of accessibility testing in a Design System. If we find errors in the relationship between components (even though the components themselves are compliant), where and how can I document these problems? Or, if a user with a disability offers a perspective beyond what we understand as accessibility with WCAG, where can I give voice to this audience?

I believe these are the challenges that, as a community, we are still figuring out.

Did you enjoy accessing the content of this retrospective? Feel free to contact me via my LinkedIn for any type of feedback.

References

APPFORCE. Designing APIs: How to ensure Accessibility in Design System components. AppForce, YouTube.

BEAUMONT, Sophie. Shifting left: how introducing accessibility earlier helps the BBC’s design system.

BEDASSE, Kristen. Design System Accessibility — UX Case Study: Accessibility improvements to an existing design system.

BHAWALKAR, Gina. My Takeaways From Config 2024: Impacts On Design Systems, Storytelling, And Accessibility. Forrester, 2024. .

BIKKANI, Aditya. A guide to accessible design system. AELData, 2024.

CODE AND THEORY. 3 Principles to Build an Engineered Design System that Improves Speed, Consistency, and Accessibility. Medium, 2024.

CODE AND THEORY. How to create an accessible design system in 60 days. Medium, 2024.

CONVEYUX. Greg Weinstein — Inclusive user research to build an accessible design system. ConveyUX, YouTube, 2024.

CUELLO, Javier. Accessible Components. Design Good Practices, 2024.

DEQUE SYSTEMS. Making Pinterest more inclusive through design systems — axe-con 2023. Deque Systems, YouTube, 2024.

DIGITALGOV. Component-based accessibility tests for the U.S. Web Design System. DigitalGov, YouTube, 2024.

FABLE. Power up your design system with accessibility testing. Fable, 2024.

FIGMA. In the file: Design Systems and Accessibility | Figma. Figma, YouTube, 2024.

FRONTEND ENGINEERING & DESIGN SOUTH AFRICA (FEDSA). The NL Design System And Why Accessibility Matters — Hidde de Vries. FEDSA, YouTube, 2024.

GEORGIEV, Georgi. The importance of high contrast mode in a design system. Pros, 2024.

GET STARK. How to use your design system colors to fix accessibility issues with Stark in Figma and the browser. Get Stark, 2024.

HAWKINS, Tyler. Scaling accessibility at Webflow. Webflow, 2024.

HI INTERACTIVE. UX and design systems in retail: inclusivity, accessibility, and innovation — Hi Talks #10. Hi Interactive, YouTube, 2024.

INTO DESIGN SYSTEMS. Design systems accessibility meetup — Component review. Into Design Systems, YouTube, 2024.

INTO DESIGN SYSTEMS. Design tokens sets for accessibility needs — Marcelo Paiva at Into Design Systems Conference. Into Design Systems, YouTube, 2024.

JOER, Jairus. Develop design systems with accessibility in mind. Aggregata, 2024.

KNAPSACK. Making design systems inclusive with accessibility specialist Daniel Henderson-Ede. Knapsack, Youtube, 2024.

KORNOVSKA, Diyana. Building accessibility into design systems. Resolute Software, 2024.

LAGO, Ernesto. Accessibility Best Practices for Design Systems. LinkedIn, 2024.

LAGO, Ernesto. An Intro to Accessibility in Design Systems. LinkedIn, 2024. .

LAMBATE, Fahad. Designing for inclusivity: the Shift Left approach towards accessible design systems (ADS). Barrier Break, 2024.

LYNN, Jamie. Accessible design systems. Jamie Lynn Design, 2024.

MILLER, Lindsay. The importance of accessibility in design systems. Font Awesome, 2024.

NL DESIGN SYSTEM. Using USWDS accessibility tests to improve accessibility — Amy Cole — Design Systems Week 2024. NL Design System, YouTube, 2024.

ROMERO, Cintia. Accessibility in design systems: a comprehensive approach through documentation and assets. Supernova, 2024.

STANKOVIC, Darko. Accessibility in Design Systems. Balkan Bros, 2024.

TESTDEVLAB. QualityForge: Speaker #5: Adrián Bolonio — Design systems and how to use them in an accessible way. TestDevLab, YouTube, 2024.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN THEORY. Creating an accessible design system. Universal Design Theory, 2024.

UXCAMP AUSTRALIA. Simon Mateljan | Baking accessibility into your design system. UXCamp Australia, YouTube, 2024.

UXCON VIENNA. (In)accessible design systems: doing things wrong to get it right — Wendy Fox — uxcon Vienna 2023. UxCon Vienna, YouTube, 2024.

VAUGHAN, Maggie. Essential principles of accessible design systems. Dubbot, 2024.

WEBAIM. Homer Gaines: Improving accessibility through design systems. WebAIM, YouTube, 2024.

ZEROHEIGHT. Back to school with Amy Hupe & Geri Reid: Accessibility and design systems. Zeroheight, YouTube, 2024.

Design systems and accessibility—a 2024 retrospective was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.