Today’s hiring technology is experiencing an arms race — between hiring managers and candidates — with both groups attempting to process the most applications with the least human contact: the result is a bizarre mockery of the idea of hiring, absent human decency.

Having recently changed my day job, I have had a lot of contact with the tools and practices of hiring: the majority of the aforementioned, alongside the treatment of candidates, has been appalling. I can’t claim to point to the ultimate cause, but the result is the dehumanization of candidates by analytical, AI and automated solutions that hiring managers turn to in order to deal with the unmanageable deluge of resumes from candidates who have turned also to scale and to AI.

I will address the following irritants:

- PDF as a prime means of data transmission (for resumes)

- Applicant Tracking Systems (ATS) and the new need to keyword-optimize our resumes

- The habit of companies to decline candidates without explaining their reasons or giving candidates a means to reply

Unsurprisingly, I have a few recommendations for reform.

PDFs and data exchange

More or less, all jobs posts today require you to detail your work history, skills and education. Most commonly, candidates can have the hiring system “read” their resume, or have the data pulled from their LinkedIn profile, or in more rare cases submit it manually.

All of these options are bad. Manually copying and pasting one’s experience into the requisite boxes is slow and tedious. LinkedIn is fast and direct, but it is a monopoly in its space, which is a problem in itself.

Then we have the PDF-parsers, which range from tolerable to hilariously bad: garbling dates, reversing fields like locations and title, and sometimes apparently plucking information from nowhere. This is even after formatting my resume within special tools designed to create parsable PDFs. Note that for jobs that don’t allow you to submit experience via LinkedIn, often you must submit either by PDF parse or manually. This, compounded over days and weeks of applications, is humiliating.

In addition, PDFs have innate problems as means of information transmission. Most of the PDF standard has been in the public domain since 2008, but working with PDFs feels like working with a proprietary standard like .doc: one must wrestle either with free/open tools that are at best fair quality or use full-featured but bloated and glacially slow proprietary tools, and work around inexplicable differences in formatting between systems.

With PDF, something is always broken.

This of course raises the question: why do we use PDFs? We do because PDFs are a means of fixing text and images on a page with purported portability between systems. But why does it actually need to be on a page? I say it doesn’t: for the majority of candidates, what matters is the organized textual expression of what they can do. Assuming the text is readable, the layout is irrelevant except as a showcase of design skills for relevant professions.

Indeed, layout is a stumbling block: the best-looking PDFs that can be made by non-designers are built in PDF-building tools. These tools are decent, but the prettiness comes at the cost of inflexibility: no tweaks to layout or font size are possible, meaning that one is constantly fighting character count, for example, to keep things on one page. PDF, like email, comes also with the anachronism of baked-in line-breaks.

Today text, just text, verges on universality and openness, flows to fit the allotted space offered by various devices and applications: not so with PDF.

A moment spent on deleting spurious carriage returns or editing to keep things on a single page is a moment spent on something irrelevant to what actually matters: one’s aptitude.

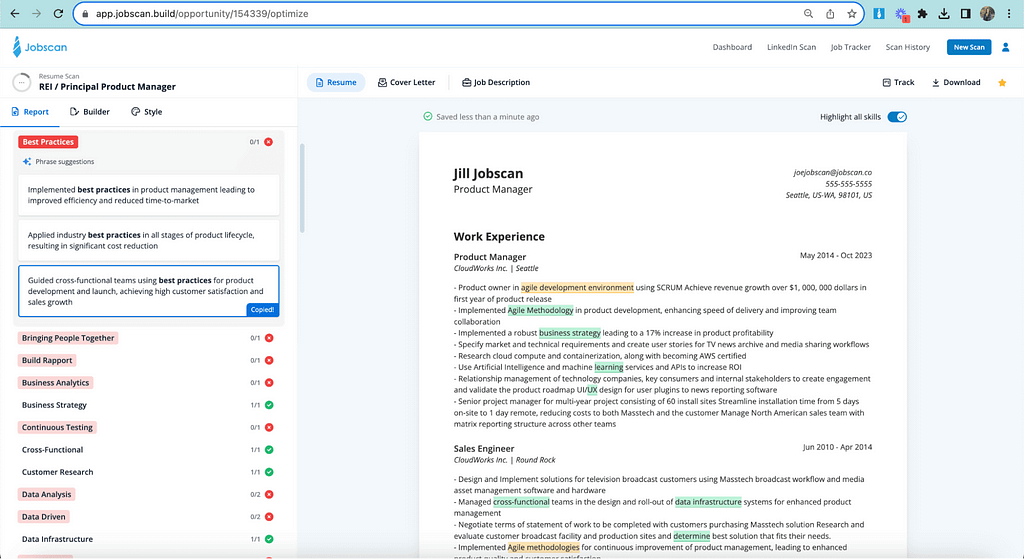

ATSs and keyword optimization

There’s good reason to think that candidates who optimize their resumes with keywords found in the job description have a better chance of being interviewed. This is supposedly because ATSs perform a keyword analysis on resumes as a purported measure of relevance. As with search engine (SEO) keyword optimization, this is a signal that the system is broken: the act of taking words from the job description and putting them into your resume is formulaic, therefore demonstrating nothing nontrivial about one’s qualities.

The fact that it’s possible for it to change one’s chance of getting an interview suggests that hiring managers are dealing with a scale of applicants and/or lack necessary tools such that they cannot make real judgments on candidates.

Meanwhile, if you eliminate candidates based on keyword analysis, this will eliminate candidates who have either not heard that keyword optimization can help or who refuse to do so, feeling that it is deceptive (these people should be hired).

The picture of resumes will therefore, become something like the Web in around 2010: having discovered “keyword stuffing,” webmasters gained rankings for thin, derivative rewrites of rewrites, while real ideas languished.

As with SEO, this distortion comes from a bad information system (the Web) that lacks a decent indexing, categorization and intercomparison system. Thus, instead of using resumes to exchange information, we have a new arms race: the employers use ATSs to filter us, and we keyword optimize: this arms race cannot be won, and we will continue it at the expense of our time and self-respect.

To see the evidence against me, and to confront my accuser

I’d like to draw attention to an excellent presentation by Casey Muratory, given earlier this year during FUTO’s Don’t Be Evil Summit. Muratory taks about the process of people being thrown off platforms such as Twitter and YouTube, and claims that these processes would be fairer and have better outcomes if the platforms in question implemented some norms from the legal system, notably the right to know the evidence against oneself and to discuss the situation with the person making the decision.*

https://medium.com/media/99d29bcac2ad4f66f918ab339614238c/href

I think that we should apply something similar to hiring. In hiring, both of these principles are violated almost universally, see an example application response below:

Subject: An update on your application to ***** — Partner Marketing Manager — *****

Dear Oliver,

Thank you for your application to the Partner Marketing Manager — ***** role at *****. We are writing to let you know that we have reviewed your application. We regret to inform you that we shall not be progressing your application further for this particular role.

We appreciate that you considered us for your next career step and hope that you maintain interest in ***** and our products. If you would like to apply for other new openings we would be happy to consider you.

Regards,

*****

There is no explanation of how my application was lacking. Too little experience? To much of a jump from my current title? Prefer someone on the West Coast? Not enough keywords?

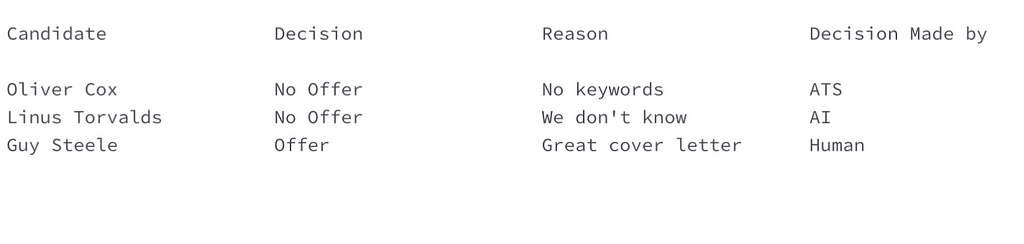

How did they make the decision? AI? A human? An algorithm?

In that they can arrange to have this email sent and to include the job title and my name — automatically — they could include their reasoning. Not including information that could be included at no cost to anyone is called hiding it. I suspect they hide it because they dismissed my application out of hand algorithmically or with the help of AI: it’s their right to do so, but I have the right to know.

This would of course be galling news, but it would help us candidates immensely to who (or what) and makes these decisions, and how. Indeed, knowing that an algorithm made the decision, say, and that it was based on lack of requisite keywords would help me know that this is something I should focus on in future applications. And if they admit to using AI for this purpose, that’s the evidence we need to push back.

Let’s say, dear reader, that you disagree that we candidates have a right derived from common decency to this information: fair enough. But let me put it this way: informing candidates about how decisions are actually made will benefit the companies, in that our applications will be better suited to their systems. And, if we know that a given application is destined to fail, we won’t waste their time with it.

Of course, truly frivolous applicants don’t have such rights, but I’m treated like a frivolous applicant much of the time, even in response to heartfelt cover letters, detailed answers, even after for one application looking at the % of people in the UK who got the same grade as I did in English to see how good, relatively, my grade was.

It would be useful to know what the hiring manager or machine actually did. Did they look at my answers to their questions? Watch the introductory video I made?

I once experimented with taking time to write long, detailed cover letters that respond to the company’s situation and brand, and the results were the same as for any other application I had submitted. Did someone read it? Tell us what we need to do and what will help us succeed.

We will do it.

Then there’s the no-reply emails. If the company tells me it’s a “no” from a no-reply, I have no recourse to dispute the decisions and no way to ask for feedback, or, so to speak, to confront my accuser. This is a sad return of the idea that a computer (which, let’s face it, is likely making most of these decisions) cannot err, and by extension that there is no need to be able to query its decision. I can of course fill in the company’s contact form: but what good is that actually going to do.

Remember, mistakes happen: it may seem absurd, but what if I was the best candidate and the hiring manager accidentally pressed the wrong button? AI makes frequent and colorful mistakes. What if I made a mistake and, realizing it, wanted to let them know after my application had been rejected. Often I’m confronted with US applications that require a GPA. I don’t have a GPA because I studied in the UK: will they read my explanation? How can I be sure if I can’t ask?

Proposals

Below, I set out some proposals on how to improve things.

A better information system

The solution to the absurdity of PDFs is obvious: job seekers should maintain their work history, skills and interests in a standardized format, rendered in plain text. Ideally it would be accessible online via a URL, but you could equally store it as a file. Note that this is not a document; the fields, like employment dates, titles, etc. would be stored to allow universally accurate parsing by computer.

Designers and others for whom the visuals are important could maintain both designed resumes and a system like this to optimize for both sides of the equation.

My company, HSM, is building a broader solution to the superset of this problem: the proper organization of text, its ownership and control by users.

No no-reason, no no-reply

No-reason decline emails can be abolished immediately at little to no cost: there is no excuse. No-reply emails should be abolished also: the initial result of this will be a deluge of correspondence (much of it warranted, I’m sure) but then hiring managers will be forced to raise the bar to reduce the volume of applications: this is good thing, we candidates apply to too many jobs.

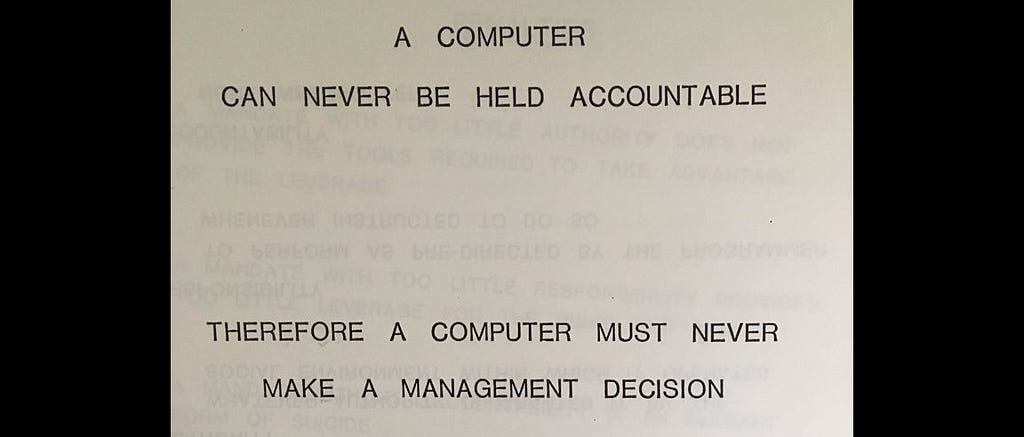

No AI

For the most part, I think that AI (read LLMs) should have no application in hiring (and probably most other fields). Using it abdicates responsibility to a system whose decisions are definitionally impossible to interrogate, which is immoral. For more on this, see my longer discussion of AI, “Artificial Intelligence: The Soul of Soulless Conditions.”

If you don’t have time to read it, I defer to a famous slide from an IBM presentation on the subject:

Talk to failed candidates

A friend of mine, when laid off, asked whether there would be an exit interview. His boss responded by saying that there would not be, as his was an involuntary termination. What a odd proposition: that this individual, because he was being let go, had nothing useful to offer the company by way of feedback or praise. The same is true for failed candidates: they have a lot to say of much use, but nobody reaches out.

I got a survey once; the first question was: “Did the job description make it clear to you what the role would entail?” I didn’t read any further.

Walk the walk

Finally, any company that uses PDF parsing, keyword-oriented ATS systems, AI, and that hits candidates with no-reason, no-reply messages should mandate that any hiring manager and anyone who has a hiring manager report to them must apply for their own job with such a system every quarter. This will I hope make them realize firsthand that these systems would be hilarious if they weren’t so dehumanizing, and will spur change from a sense of disgust.

Conclusion

There is foul play on both sides here: candidates apply to hundreds of jobs when they probably shouldn’t, and use AI to help when they definitely shouldn’t. This overwhelms hiring managers, who then need systems to deal with the quantity. The question of who started matters less than the fact that both sides are stuck in this trough: they use computers on us, so we act like computers in order to survive.

A candidate who applies for a reasonable number of jobs or shuns keyword optimization software hurts only themself; companies must act first, as they have the scale and the clout to do something.

All this seems to have happened thanks to the computer adding scale to and subtracting personality from our interactions. Indeed, interacting with real people can be hard and awkward, especially if it’s bad news. But surely personality is what it’s all about. Indeed it feels that we subject our personalities to such scale that they risk thinning out into an undifferentiated haze or, like a balloon in a vacuum, expanding rapidly and going pop.

*I note that the question of online platform access is controversial and polarized. However, if you feel that this cause belongs to people who don’t think like you do, I encourage you to seek examples of de-platforming when someone like you was the victim, or even to read about non-political examples (all exist). I ask you then to tell me if Muratory’s proposals would make things worse: please comment or contact me. This is for now putting the costs of implementing his proposals to one side: they would be considerable, but the most relevant platform companies have similarly considerable amounts of money.

Why is hiring software so impersonal? was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.