A guide to the extinction of user joy in the digital age.

I was halfway through doing the dishes while listening to a podcast when an ad cut through and interrupted one of the most interesting bits. My phone was a few meters away in the living room and I rushed over like I had forgotten a burning turkey in the oven to make sure that I got to the phone before the second ad started playing. I tapped that lower-right hand skip button and the tension in my body temporarily melted away as I made my way back to the chore and continued listening to my podcast, ironically about the slow decay of once useful apps, that was so rudely interrupted by a Nissan ad.

As I pondered how possible it would be to find an ad blocker for my phone, the answer was slapped in my face in the form of a glorious popup! Try YouTube premium and you’ll be ad free… something that only a few years ago was standard had become a premium and I asked myself why? The term I happened to be learning about that day from Cory Doctorow was enshittification, which can be loosely defined as the process by which platforms decay as they shift value away from users and toward themselves and their business customers. In other words, things start out good for us, then get worse as the companies optimize for profit. While we all have a collective intuitive sense of platforms decaying over the last few years, I wanted to look closer from a design perspective, specifically, at how that decay unfolds through the deliberate, incremental rollout of ads.

The key players in this enshittification race are the four major tech companies that dominate our digital lives: Google, Meta (Facebook and Instagram), TikTok, and YouTube. But for the sake of this article, I’m going to focus on one in particular, because it’s where I spend the most time: YouTube.

These companies’ slow decay into ad infested dystopian nightmares reminded me of a conversation I had with my good friend and cofounder Charlie Gedeon. He told me about this theory, called carcinisation, which is the very hilarious scientific process which can be described as “the many attempts of Nature to evolve [into] a crab”. In simple terms, there is an evolutionary momentum that has slowly pushed a variety of unrelated species to evolve into the general behaviour pattern and shape of a crab. So given enough time and opportunity, every species will eventually become a crab. I couldn’t ignore the metaphorical parallel: in our technological ecosystem, the biggest species don’t turn into crabs, they turn into ads.

Before YouTube, there was TV. The TV was invented in 1939, and the first ads were shown in 1941. In the early 1940s, ads were short, mild interruptions between programs then by the 1980s, they had become pretty much the reason every sitcom, news broadcast, and sports event existed at all. It was simply the packaging for the ad breaks that paid for it. Then streaming arrived and it felt like a breath of fresh air! A new, ad-free subspecies breaking free from its commercial ancestors. Netflix, YouTube, and early Hulu gave us hope of a new evolutionary path: content without interruption. But, it didn’t stay ad free for long.

So let’s look at YouTube, starting with the first signs of life to crawl out of the primordial soup, we have the humble InVideo overlays first launched in 2007, these were thin, semi-transparent banners that floated over the bottom of a playing video, usually small text or a tiny ad image that you could close with a small “X.” These early ads didn’t stop the video, or call for too much attention. They quietly fed on our attention without killing us, like a parasitic symbiosis. While annoying, they didn’t destabilize the delicate environment of early to mid-2000’s YouTube.

Then between 2010 and 2018 there’s an explosion of life, the ads grow legs, lungs, and teeth… YouTube launched TrueView ads, those aforementioned and all too familiar skippable pre-rolls that appear before your chosen video. These ads demand visibility, they evolved to study their prey’s habits, tracking which openings held attention longest. At first, there was just one, small but intrusive, a 5-second interaction before you could skip and move on. But as we all know, evolution rewards persistence. Soon, a single ad became two, then a pair before and after your video, and finally in 2012, mid-roll ads appeared, splitting your entertainment in bite size chunks.

With each mutation, they became harder and harder to ignore. The variety was overwhelming, displaying banners above, overlays below, and videos within videos. The content creators themselves now, mimicking the copy of the ads. By the end of this period, the once teeming with life content creator ecosystem had turned into a chewed through rotting swamp where every spare patch of attention was colonized with a swarm of ads.

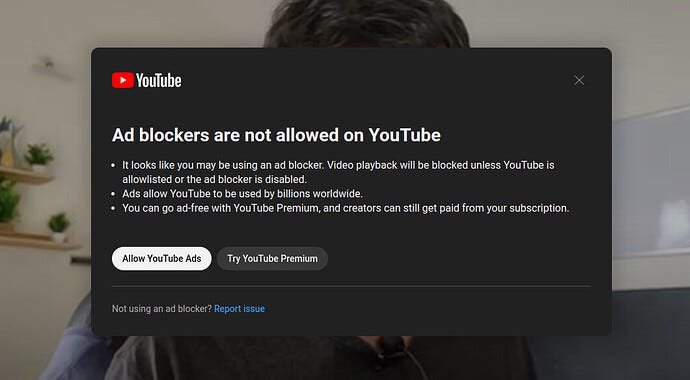

Understandably, this environment was not the most pleasant so I, like many others, used an ad-block. To put in perspective how prevalent this problem is, here’s a quote from Cory Doctorow that really struck me: “51% of web users have installed an ad blocker, it is literally the largest consumer boycott in human history.” The majority of people, which I imagine probably encompasses people making these decisions in the first place, probably have an ad blocker installed. This was our one tool to try and avoid the onslaught of ads that we’d be subjected to on a daily basis, and while there weren’t as easily accessible tools on mobile, we’d at least have a reprieve on our computers… or so we thought.

In late May of 2023, YouTube began to mutate again, starting with a small subset of tests where they rolled out banners saying “Ad Blockers are not allowed on YouTube.” An easily dismissable popup asking you to uninstall your Ad Blocker. It was the early signs of a dominant species that was going to make it impossible for you to avoid ads. Eventually, making it an unfeasible arms race between ad-blockers and ad-blocker-blockers (that’s a mouthful). This persisted to where we’re at now where it’s more of a pain to find a way to circumvent ads then to just sit through the discomfort that we’ve been conditioned to endure.

This whole process has been a calculated and heavily studied rollout. In some ways it is a masterful example of how to slowly introduce a feature to users that doesn’t actually benefit the majority. At first users feel discomfort, but not enough to abandon the platform. The designers, researchers and tech CEO’s know that they’re pushing unpleasantness and that they have to go as far as they can without causing too much pain because they understand that it’s a delicate ecosystem of attention and people will find alternatives if pushed too far too quickly. If YouTube had not given notice of its intention to block ads for months prior to the rollout of the full ad-block extinction, what would have happened? I personally think the consequences would have been cataclysmic and in some ways hoped that they would have torn off the bandaid a little more violently to shock us into action.

So over the course of 25 years, they’ve increased the heat and now we’re in a pot of boiling water, but in truth it’s we actually don’t know how much hotter it might get. Many PAID platforms now include ads, such as Prime and you have to pay additional fees to exclude them. So what comes next in this grand evolutionary chain? Maybe ads that blend seamlessly into the content, AI-generated sponsorships that mimic the creator’s voice so perfectly we can’t tell where the video ends and the commercial begins. Maybe they’ll feel like features instead of intrusions. Either way, the species isn’t going extinct anytime soon. Like crabs, like capitalism, ads always find a way.

The hope is for the next disruption. YouTube once broke the cable monopoly with creativity, and community before slowly mutating into the very thing it replaced. It would seem, that’s the pattern of evolution, the old ecosystem collapses under its own weight, and something new crawls out of the primordial muck.

One can hope that there is a better answer gestating. Maybe it’s decentralized video, maybe it’s a new model of sharing that doesn’t depend on monetized attention, more than likely it’s something we haven’t imagined yet. The godfather of the term, Cory Doctorow, explores this in his new book Enshittification: Why Everything Suddenly Got Worse and What to Do About It , with the most important part being that final clause: what to do about it.

As citizens, we can advocate for antitrust laws, interoperability, and policies that prevent platforms from locking in both users and creators. As users, we can choose to support the smaller, values-driven platforms that still have a soul, ones that remind us the internet doesn’t have to be stinky pile of ads, but a place we actively connect. And lastly as designers, we can embed the values of portability, transparency, user control, and minimal hidden value extraction. Better than hoping for the next better thing is putting our efforts into actually designing it.

The evolution of Youtube: How every platform evolves into an ad machine was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.